How Bad Would Eliminating Social Security’s Deficit Feel?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

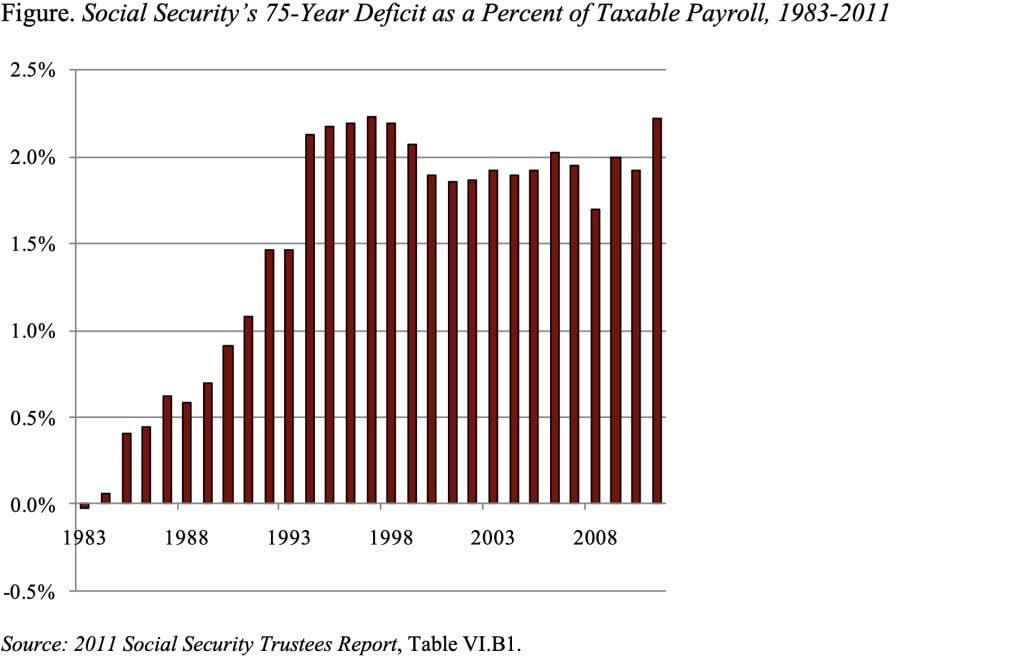

Each year the Trustees of the Social Security system report on its financial health over the next 75 years. The 2011 Report shows that, despite reduced revenues and increased benefit claims in the short run, the system continues to face a 75-year deficit equal to about 2 percent of taxable payroll (see Figure).

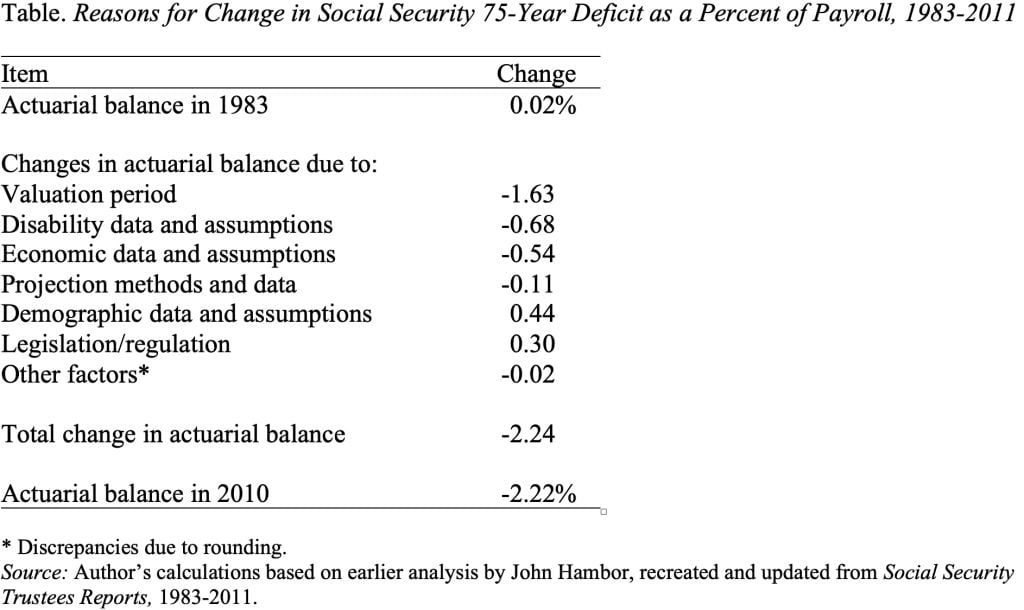

The shortfalls over the last two decades are in sharp contrast to the projection of a 75-year balance in 1983 when Congress enacted the recommendations of the so-called Greenspan Commission. The Table shows the reasons for the shift from a 0.02 surplus in 1983 to a deficit of 2.22 percent in 2011. Leading the list is the impact of changing the valuation period. That is, the 1983 Report looked at the system’s finances over the period 1983-2057; the projection period for the 2011 Report is 2011-2085. Each time the valuation period moves out one year, it picks up a year with a large negative balance. Persistent increases in disability rolls and worsening of economic assumptions – primarily a decline in assumed productivity growth and the impact of the recent recession – also contributed to the deficit. Offsetting the negative factors has been changes in demographic assumptions – primarily higher mortality for women – and the effect of regulation and legislation, such as the Affordable Care Act of 2010.

Is a 75-year deficit of 2.22 percent of taxable payrolls big or small? One way to think about it is the amount by which the payroll tax would have to increase for the government to be able to pay the current package of benefits for everyone through 2085. That is, if payroll taxes were raised immediately by 2.22 percentage points – 1.11 percentage points each for the employee and the employer – the system would be in 75-year balance.

How bad would a 1.1 percentage-point increase in the payroll tax feel? We may be about to find out. The Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010 reduced the Social Security payroll tax rate for 2011 by 2 percentage points for employees and the self-employed. (The Treasury makes up for this reduction by transferring general revenues to the trust funds, so it has no financial implications for Social Security’s short- or long-term outlook.) The tax is scheduled to rebound to its original level in January 2012. (Whether such an increase will actually occur in an election year is another story!) Thus, the scheduled increase for employees in 2012 is twice the size of that required to restore balance for 75 years. It will be interesting to see if anyone even notices.

One final note, a lasting fix for Social Security would require that the payroll tax increase be accompanied by some other changes. Solutions that provide just enough to restore balance for the next 75 years leave the system in deficit in the 76th year. The most logical adjustment on the benefit side would be to index the full retirement age (after it reaches 67) to improvements in longevity. Those two changes – a 1-percentage-point increase in the payroll tax for employees and employers and indexing the full retirement age to longevity – would take us a long way towards a permanent solution. And I bet that it would be almost painless.