Population Aging and the Labor Force

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

An aging population lowers participation rates, but those who do participate are more likely to be employed

A recent Goldman Sachs study focused attention on the impact of population aging on labor force participation. The authors had a much more ambitious goal than the simple point that I would like to emphasize. They were trying to determine whether the sharp decline in the labor force participation rate (the percent of the working population either employed or looking for work) since the financial crisis and Great Recession was a function of structural factors or weak demand. To do that analysis, however, they needed to isolate the portion of the drop in labor force participation that was not due to population aging.

By the time of the study, labor force participation had fallen 2.7 percentage points since the start of the 2007-2009 recession. Some of this decline was clearly due to population aging, which shifts the composition of the working-age population towards those groups with lower labor force participation rates. That is, 30-35 year olds have higher labor force participation rates than 55-60 year olds. As the share of 55-60 year olds in the population increases and the share of 30-35 year olds decreases, the labor force participation rate would be expected to decline.

To isolate the impact of population aging, the study compared the actual overall labor force participation rate with an adjusted rate that kept the age (and gender) composition of the population constant at their December 2007 levels. This exercise showed that 1.2 percentage points of the 2.7 percentage-point cumulative decline was due to population aging.

The Goldman Sachs study then proceeded to determine whether the remaining 1.5 percent decline in overall labor force participation (attributable to other than population aging) since 2007 was due to structural or cyclical factors. Using quarterly data for 50 states for the period since 1995, they concluded that labor demand shocks had a large and long-lasting effect on labor force participation. The impact in their model is so long-lasting that they expect labor force participation to remain flat for the next few years.

The adjustment of labor force variables for age/sex composition of the population reminded me of the enthusiasm in the 1980s to make similar adjustments to the unemployment rate (the percent of those in the labor force not able to find a job). The concern at that time was that policymakers were overestimating what constituted “full employment.” During the 1970s, the unemployment rate associated with full employment had increased as the baby boom entered the workforce. Young workers traditionally experience spells of unemployment as they enter the labor force while looking for their first job or while shuttling between work and school. They are also more likely to change jobs, resulting in additional stretches of unemployment. Since the 1970s, the share of younger people in the labor force has declined, reducing the full employment rate by about 0.5 percentage points. [Factors other than age also affect the full employment rate – educational attainment, the rate of incarceration, the increase in the disability rolls etc. – but the focus here is on aging.]

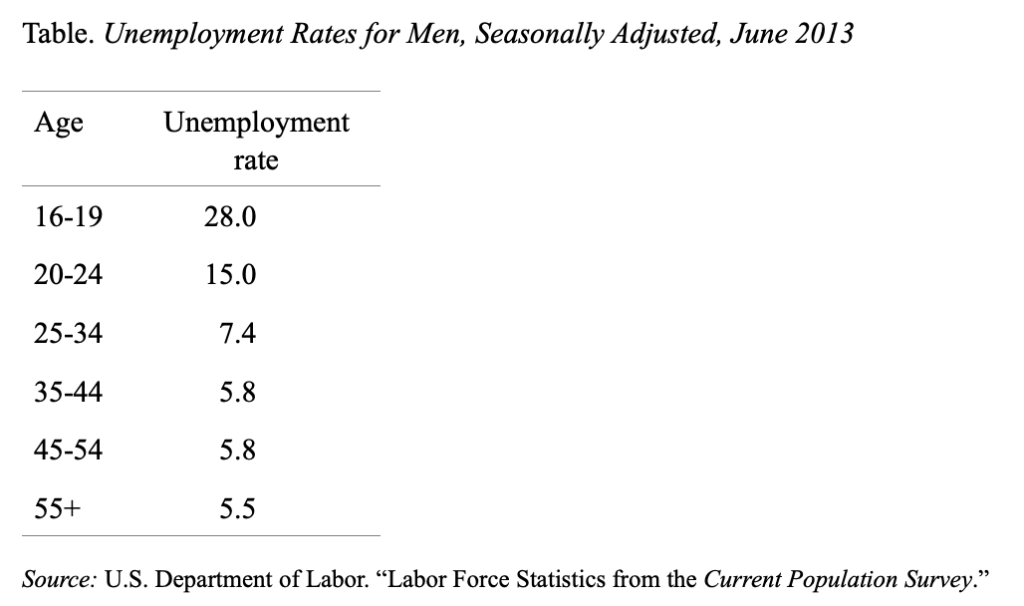

Going forward, the aging of the population should continue to lower the full employment rate, because while older groups participate to a lesser extent than younger ones in the labor force, those who do participate are less likely to be unemployed (see Table).

The bottom line is that we are in the process of a dramatic demographic change – the rapid aging of the population – and that change has implications for the participation and unemployment figures that we see every month. We should pay attention.