Fixing Social Security Is Not Hard, and Everybody Would Feel Better

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Trustees Report continues to show 75-year deficits and exhaustion of trust fund in early 2030s.

The 2024 Social Security Trustees Report repeats the drumbeat that the Social Security program faces a deficit equal to 3.50 percent of payroll over the next 75 years and that its trust fund is scheduled for exhaustion in the early 2030s.

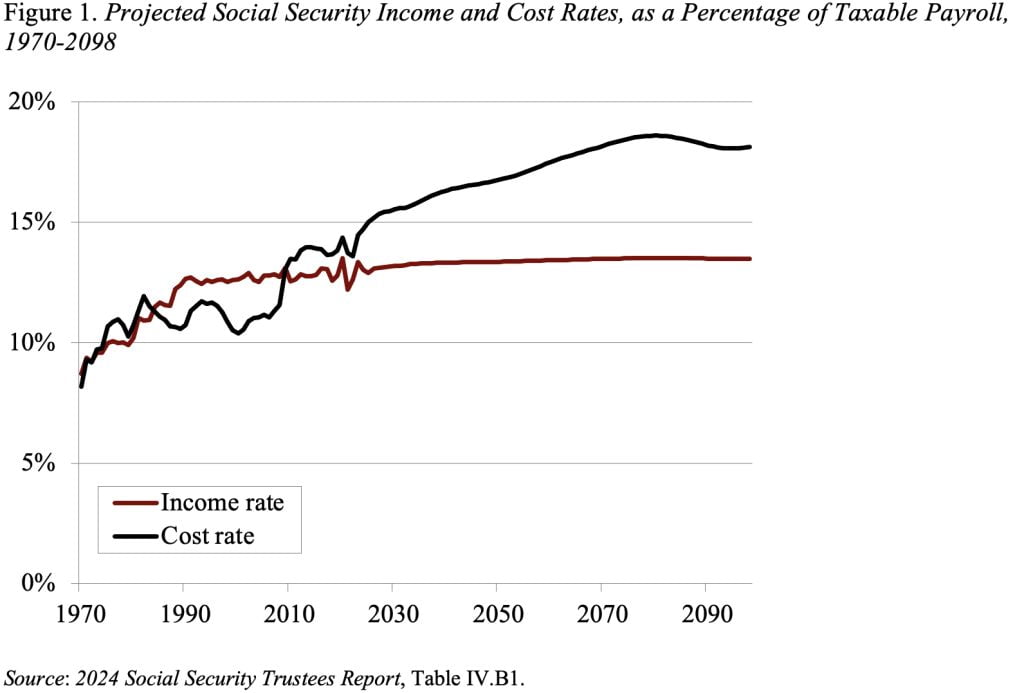

The 75-year deficit is the result of a constant tax rate and increasing costs. The increase in costs is driven by the demographics, specifically the drop in the total fertility rate after the Baby-Boom period. The combined effects of a slow-growing labor force and the retirement of Boomers reduce the ratio of workers to retirees from 3:1 to 2:1 and raise costs commensurately (see Figure 1).

The 75-year deficit is the difference between the present discounted value of scheduled benefits and the present discounted value of future taxes plus the assets in the trust fund. This calculation shows that Social Security’s long-run deficit is projected to equal 3.50 percent of covered payroll earnings. That figure means that if payroll taxes were raised immediately by 3.50 percentage points – 1.75 percentage points each for the employee and the employer – the government would be able to pay the current package of benefits for everyone who reaches retirement age through 2098, with a one-year reserve at the end.

The 75-year cash flow deficit is mitigated somewhat by the existence of a trust fund, with assets currently equal to roughly two years of benefits. These assets are the result of cash flow surpluses that began in response to reforms enacted in 1983. The retirement (OASI) trust fund is projected to be depleted in 2033. Yes, the Disability Insurance (DI) trust fund has enough to pay benefits for the full 75-year period, so the date of depletion for the combined OASDI trust funds has moved back a year to 2035. But combining the two systems would require a change in the law; hence, under current law the action-forcing date is 2033 – nine years from now.

It is crucial to emphasize that the depletion of the trust fund does not mean that OASI is “bankrupt.” At the time of depletion, payroll tax revenues keep rolling in and can cover 79 percent of currently legislated benefits. (If the OASI and DI trust funds were merged, the coverage numbers would be 83 percent.) Relying only on current tax revenues, however, means that benefits would be cut about 20 percent for both current retirees and future beneficiaries

The bottom line is that we are going to have to either come up with more money or cut Social Security benefits in the 2030s. My view is that we should increase revenues and maintain benefits. That view is based on the wobbly state of the rest of our retirement system: 1) only about half of individuals in the private sector, at any moment in time, work for an employer with a retirement plan; and 2) for most of those lucky enough to have a plan, their 401(k)/IRA holdings are modest.

Fixing Social Security is not a big deal. The shortfall equals only 1 percent of GDP, and the changes required are well within the bounds of fluctuations of other programs. Doing it sooner rather than later would keep more options open, distribute the burden more equitably across cohorts, and most importantly, restore confidence in the nation’s major retirement program.