Solving Social Security’s Funding Shortfall Requires Acknowledging Uncertainty

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

We know what we are dealing with, and can take steps to address it.

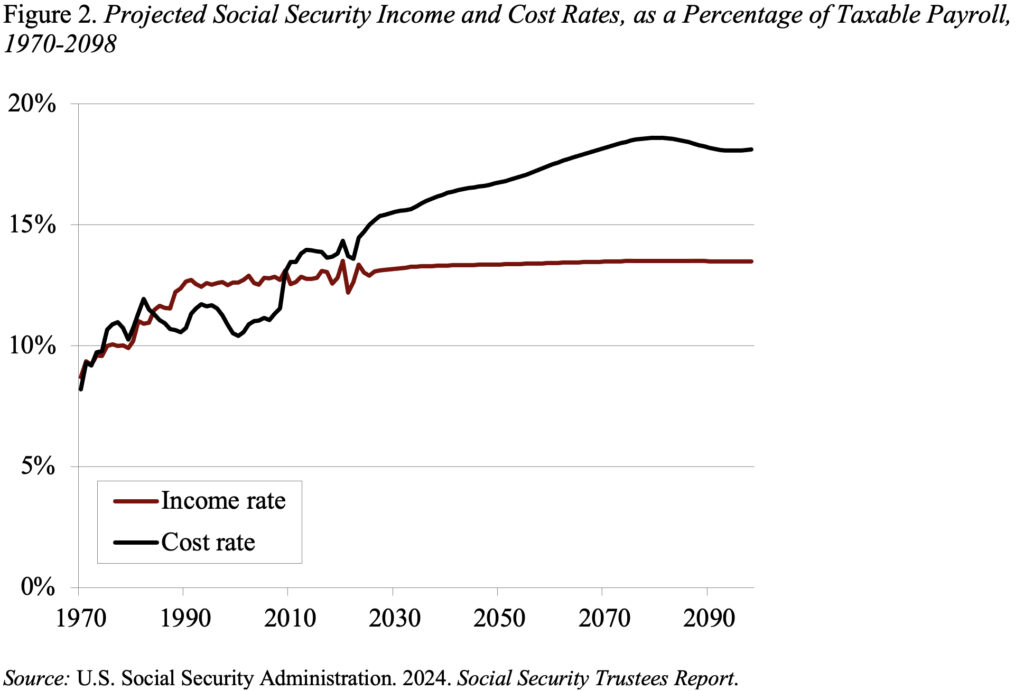

The key metric used to summarize Social Security’s financial status is the 75-year deficit. This number is the present discounted value of scheduled taxes (plus the existing trust fund) minus the present discounted value of scheduled benefits divided by the present discounted value of future payrolls. In 2024, the Social Security Trustees had an estimated deficit equal to 3.50 percent of taxable payroll. That figure means that if payroll taxes were raised immediately by 3.50 percentage points – 1.75 percentage points each for the employee and the employer – the government would be able to pay the current package of benefits for everyone who reaches retirement age at least through 2098.

But the story is a little more complicated for two reasons. First, the Congressional Budget Office also estimates the 75-year deficit, and that agency’s number is noticeably higher. Second, deficits that will occur at the end of the 75-year period should also be considered.

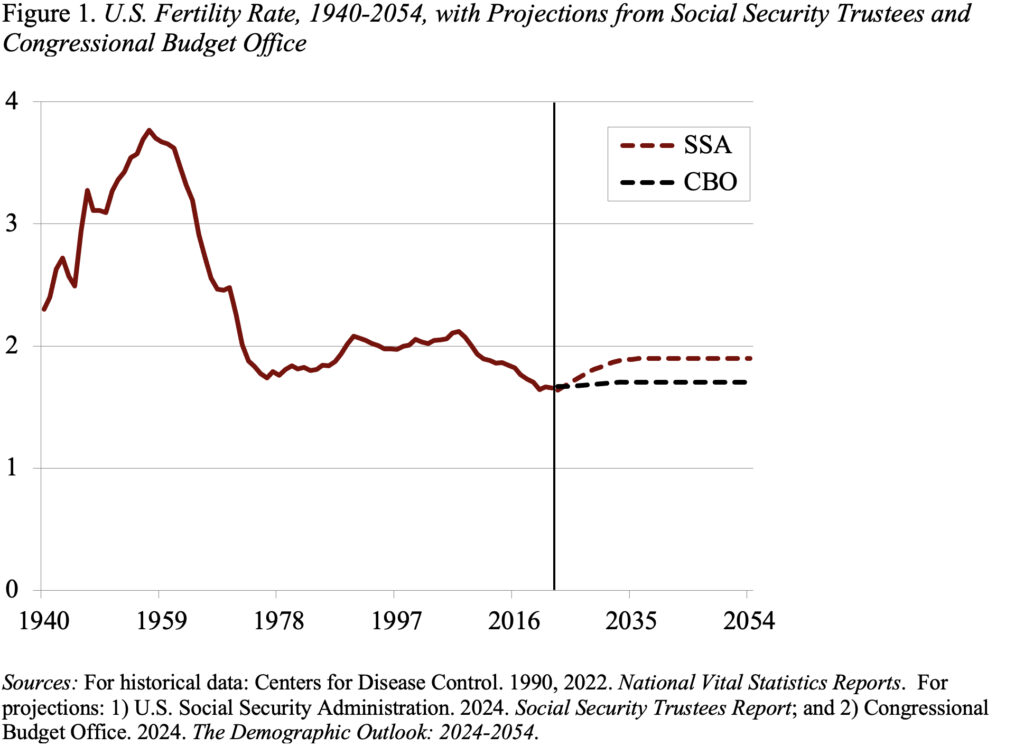

CBO projects a 75-year deficit of 4.4 percent of taxable payrolls, compared to Social Security’s 3.5 percent. The main reason for the difference is an assumption about the ultimate total fertility rate – the number of children a woman would be expected to have over her childbearing years. Demographics are a central factor in any pay-as-you-go system. The increase in Social Security costs has been driven by the drop in the total fertility rate after the Baby Boom. Women of childbearing age in 1964 had an average of 3.2 children; by 1974 that number had dropped to 1.8. The combined effects of the retirement of Baby Boomers and a slow-growing labor force due to the decline in fertility reduce the ratio of workers to retirees from about 3:1 to 2:1 and raise costs commensurately.

Although the U.S. fertility rate rebounded in the 1990s to over 2 children, it declined sharply during the Great Recession and, despite expectations of a second rebound, clocked in at 1.66 in 2022 (see Figure 1). In response to the persistent decline, Social Security lowered its ultimate assumption to 1.9 in 2024, while CBO moved to 1.7. Since fertility rates are low worldwide and show little sign of reverting to previous levels, the CBO assumption may be right. In that case, the Social Security actuaries’ sensitivity analysis suggests that the 75-year deficit could be closer to 4 percent of taxable payrolls rather than 3.5 percent.

The second issue has always been around. At this point in time, solving the 75-year funding problem is not the end of the story in terms of required tax increases. In the future, once the ratio of retirees to workers stabilizes and costs remain relatively constant as a percentage of payroll, any solution that solves the problem for 75 years will more or less solve the problem permanently. But, during this period of transition, any package of policy changes that restores balance only for the next 75 years will show a deficit in the following year as the projection period picks up a year with a large negative balance (see Figure 2). Thus, eliminating the 75-year shortfall should be viewed as the first step toward “sustainable solvency.”

One way to avoid repeated crises such as the one we are currently experiencing and to restore confidence in the financial stability of the Social Security program is for any package of solutions to include a mechanism that automatically adjusts revenues or benefits when shortfalls emerge in the future. The Canadians have such a backstop arrangement. If the Chief Actuary’s triennial report shows a financing shortfall over the next 75 years and policymakers cannot agree on a solution, the cost-of-living adjustment is frozen and contribution rates are increased. We don’t have to adopt the specifics of the Canadian mechanism, but some automatic adjustment should be part of any package to solve Social Security’s financing problems.

The bottom line is that we have a handle on the future costs of the Social Security program, but recognizing the uncertainty involved in any projections over a period of 75 years should be an integral part of the process.