Do Households Have a Good Sense of Their Long-Term Care Risks?

The brief’s key findings are:

- About half of older adults will end up requiring some high-intensity long-term care (LTC).

- The analysis explores whether people accurately perceive their LTC risks, comparing subjective and objective survey questions.

- It turns out that the subjective measures are not good proxies for objective risk.

- But the variation in the subjective responses suggests that Blacks, Hispanics, and women may be underestimating their risks.

- These three groups also tend to have fewer resources to cover care needs.

Introduction

Many older adults will require some long-term care (LTC) later in life, with over half needing intensive support – often for an extended period. The resources required to meet such high-intensity, long-duration needs – either informal support from family members or paid formal care – can be substantial. The question is whether older adults understand their risks and whether the accuracy of their perceptions varies by socioeconomic characteristics.

Despite the large literature on LTC risks and insurance, very little research has focused on whether people have a good sense of how much help they may need with daily activities as they age. Those who overestimate their risk could hold on to their nest egg and unnecessarily restrict their consumption in retirement, while those who underestimate their risk could experience unmet needs or have to spend down to qualify for Medicaid. This brief, based on a recent paper, compares two measures of self-assessed LTC risks with objective probabilities of ending up with high-intensity care needs.1

The discussion proceeds as follows. The first section provides some background on LTC risks overall, how care is provided, and the limited research on self-assessed LTC risks. The second section defines how we measure objective and subjective risks. The third section assesses whether the available measures of subjective risks capture the same concept as the objective risks. The final section concludes that neither of the subjective measures are good proxies for objective risk. But examining how the subjective responses vary by demographics does provide some useful insights. Specifically, Blacks and Hispanics appear optimistic about their future needs relative to other groups. And while women seem to be aware of average LTC risks, they may not realize that they face higher-than-average risks of needing care. These findings are concerning as these groups not only have the highest objective risks of needing high-intensity care, they also have fewer resources to provide for this care.

Background

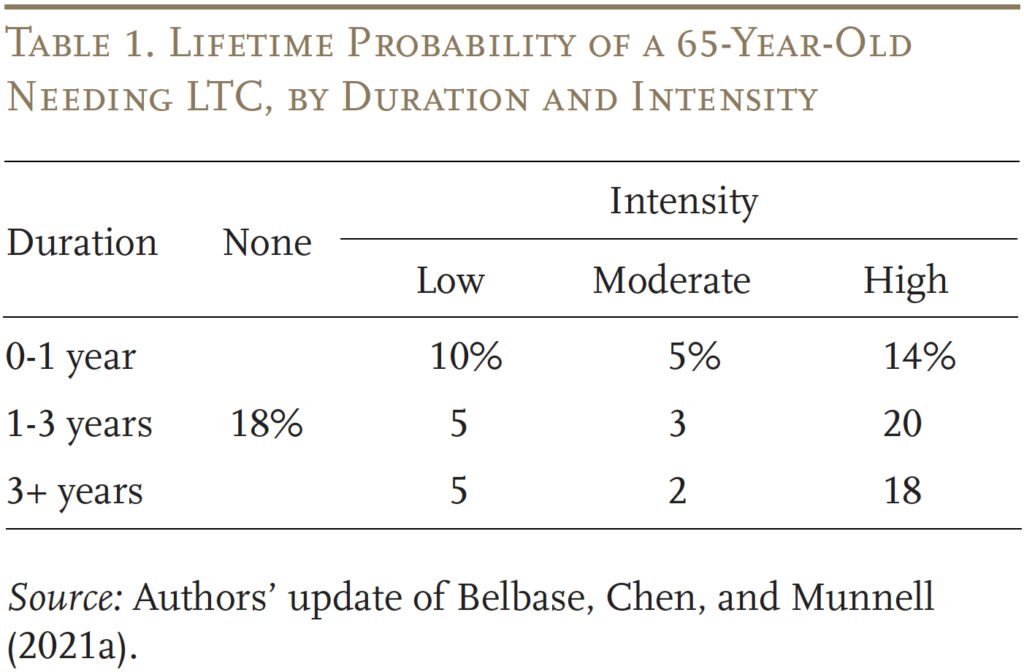

As people age, most eventually need help with housework or other instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) like shopping or preparing meals, and sometimes with more essential tasks, or activities of daily living (ADLs) like bathing, eating, and toileting. While some can get by with assistance a few times a week (low intensity), over half of older adults will have high-intensity needs – that is, require help with two or more ADLs or have an Alzheimer’s/dementia diagnosis – often for an extended period (see Table 1).2

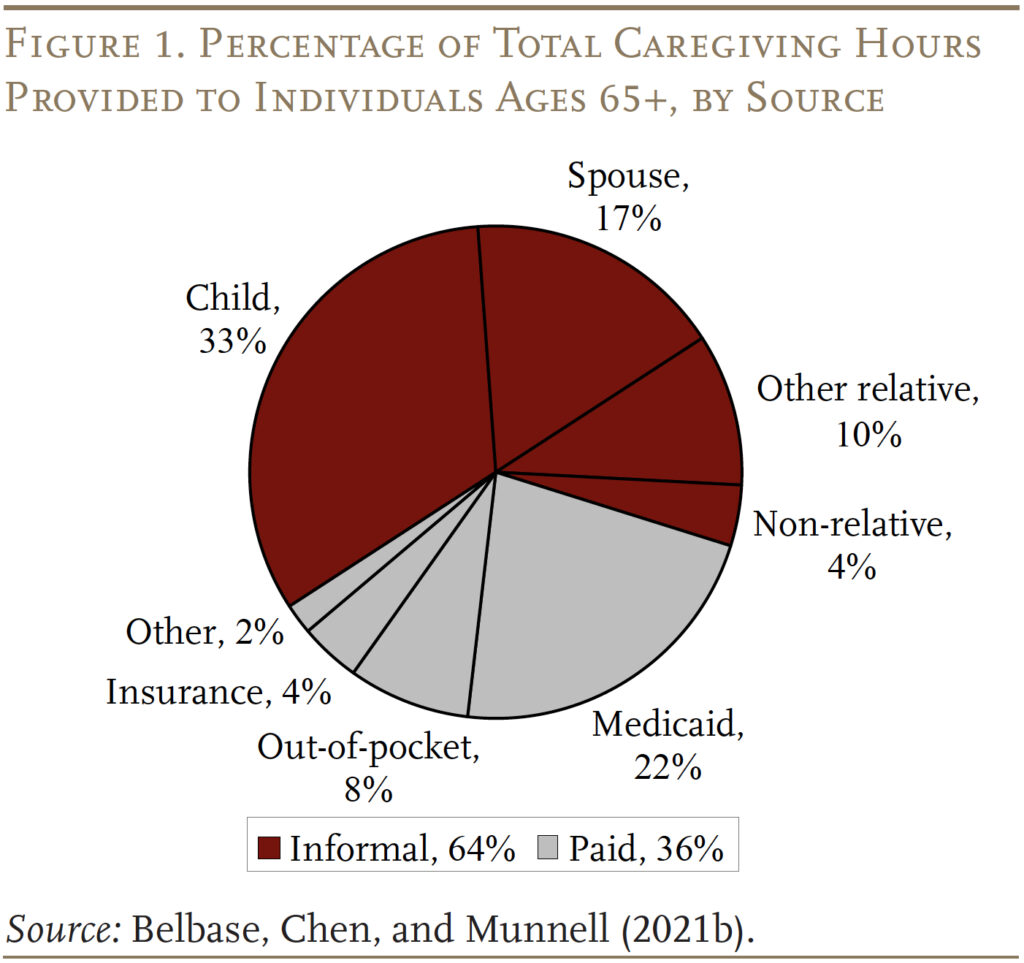

Households cover these long-term care needs in two ways. The more common way is unpaid informal care provided by family members (see Figure 1). The less common way is paid formal care, financed primarily through Medicaid or out-of-pocket. Currently, less than 5 percent of adults have long-term care insurance, and qualifying for Medicaid requires households to impoverish themselves.3

The resources required to meet high-intensity LTC needs, either from family members or paid formal care, can be substantial. To plan effectively, older adults need a realistic assessment of their risks. Unfortunately, the extent to which older adults have a good understanding of their own LTC risks is largely unknown.4

One of the few relevant studies examines the likelihood of individuals ages 72+ needing nursing home care in the next five years.5 The results show that, in aggregate, respondents have a reasonably good sense of their future nursing home needs. However, respondents who say they will likely need a nursing home in the next five years are likely to be in poor health already. It is not clear whether younger, healthier retirees or near-retirees have similar predictions about their future LTC needs.

The analysis below looks at two measures of self-assessed LTC needs and whether these measures can offer useful comparisons to predicted objective probabilities of having such needs.

Measuring Objective and Subjective Risks

The data for the analysis come from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative biennial longitudinal survey of U.S. adults ages 51 and older and their partners.

Objective Risks of High-Intensity Care

The objective measure focuses on older individuals’ risk of needing 90+ days of high-intensity care.6 For roughly 60 percent of the sample, it is possible to observe the entire lifespan of the individual and their LTC needs; for the other 40 percent, who are still alive, their lifetime needs are projected based on the experience of current and older cohorts from earlier surveys.7 Lifetime risks are based on the individual’s most severe experience. That is, a person who needs help cleaning and cooking in her 60s, then has a bout of cancer in her 70s that requires some support a few times a week, and then develops dementia in her 80s that requires around-the-clock care would be counted once and classified as having high-intensity LTC needs.

Subjective Risks of High-Intensity Care

Older adults’ self-assessed risk of needing high-intensity care comes from two HRS questions: 1) “What is the percent chance that you will ever have to move to a nursing home?” and 2) “Assuming that you are still living at age 85, what are the chances that you will be free of serious problems in thinking, reasoning, or remembering things that would interfere with your ability to manage your own affairs?”8 For both questions, participants answer with a number between 0 and 100, where 0 means they see no chance that the event will happen and 100 means they think the event will occur with certainty. In the case of the cognition question, the inverse of the response represents the respondent’s perceived risks of having serious cognitive limitations.9

Neither question is an ideal measure of the need for high-intensity LTC. For the first question, people are likely to rate their prospects of moving to a nursing home lower than their perceived LTC needs, both because nursing homes are unpopular and because people can increasingly get some high-intensity care in their own homes.10 For the second question, the wording is broad enough to cover milder forms of cognitive decline (e.g., sometimes forgetting to pay bills), which makes it likely to generate “higher” measures of perceived risk compared to a metric focused solely on dementia diagnosis.11 But these two questions are the only ones available in the HRS to serve as proxies for expected LTC.

Results

This section begins with the results for objective risks and then compares them to respondents’ self-assessed risks.

Objective Risks

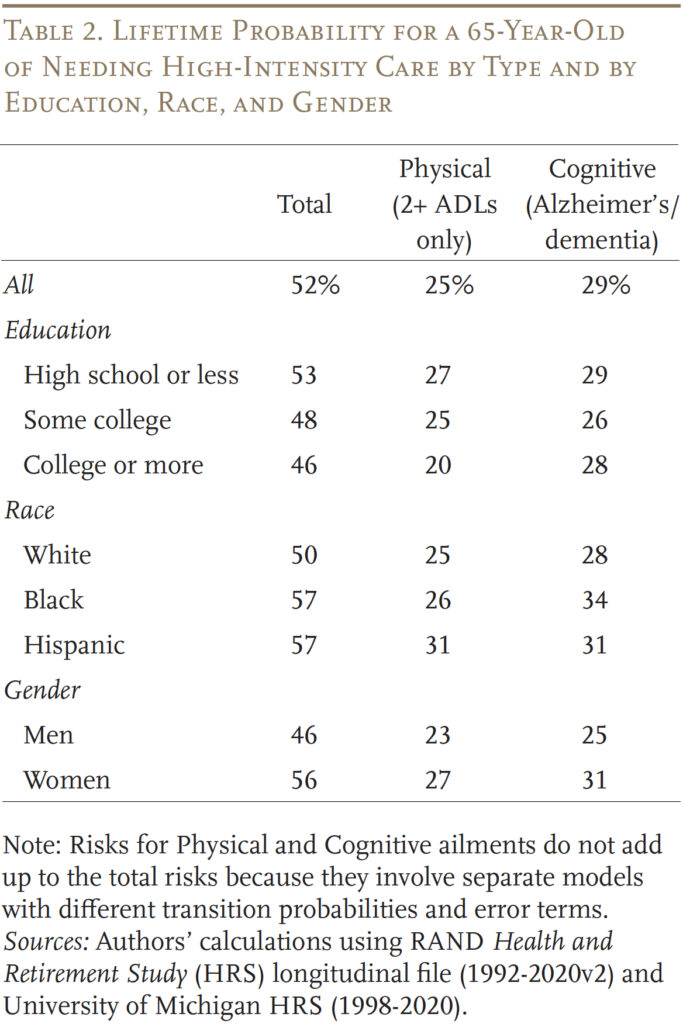

The results show that 52 percent of those 65+ will need high-intensity care for more than 90 days at some point over their remaining lifetime (see Table 2). Roughly half of those needs are generated by physical ailments and half from cognitive decline. The percentage at risk varies by education, race, and gender. Specifically, those with less education, Blacks and Hispanics, and women have a higher-than-average likelihood of needing high-intensity LTC.

Comparing Objective and Subjective Risks

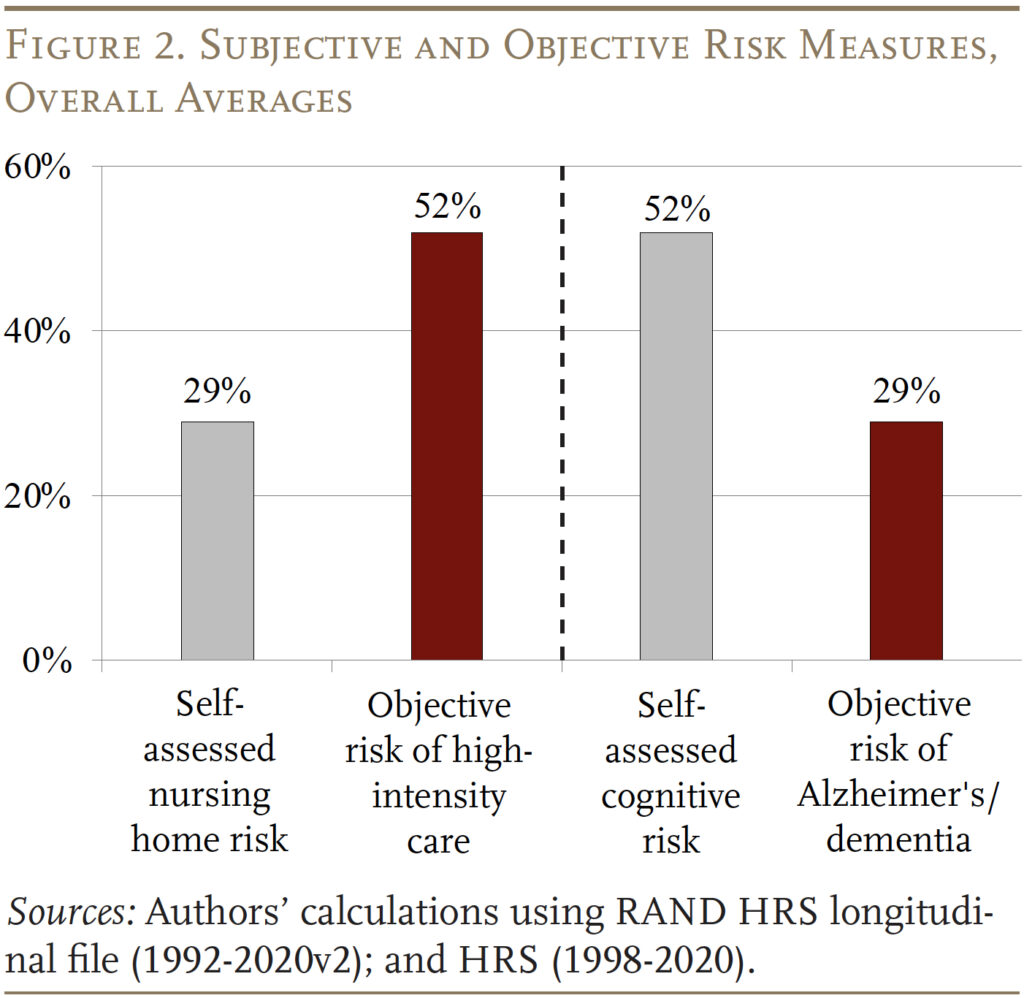

Figure 2 compares: 1) HRS respondents’ subjective risk of ever ending up in a nursing home with the objective risk of needing any high-intensity care; and 2) respondents’ subjective risk of needing help with cognitive decline with the objective diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease or other dementia. Unfortunately, these results match our expectations. Self-assessed nursing home risk – at 29 percent – is substantially lower than the objective measure of high-intensity LTC needs, as people generally dislike the idea of entering a nursing home and home care may be a viable alternative. And self-assessed cognitive risk – at 52 percent – is much higher than the objective risk of Alzheimer’s/dementia because the HRS cognitive question is so broad.

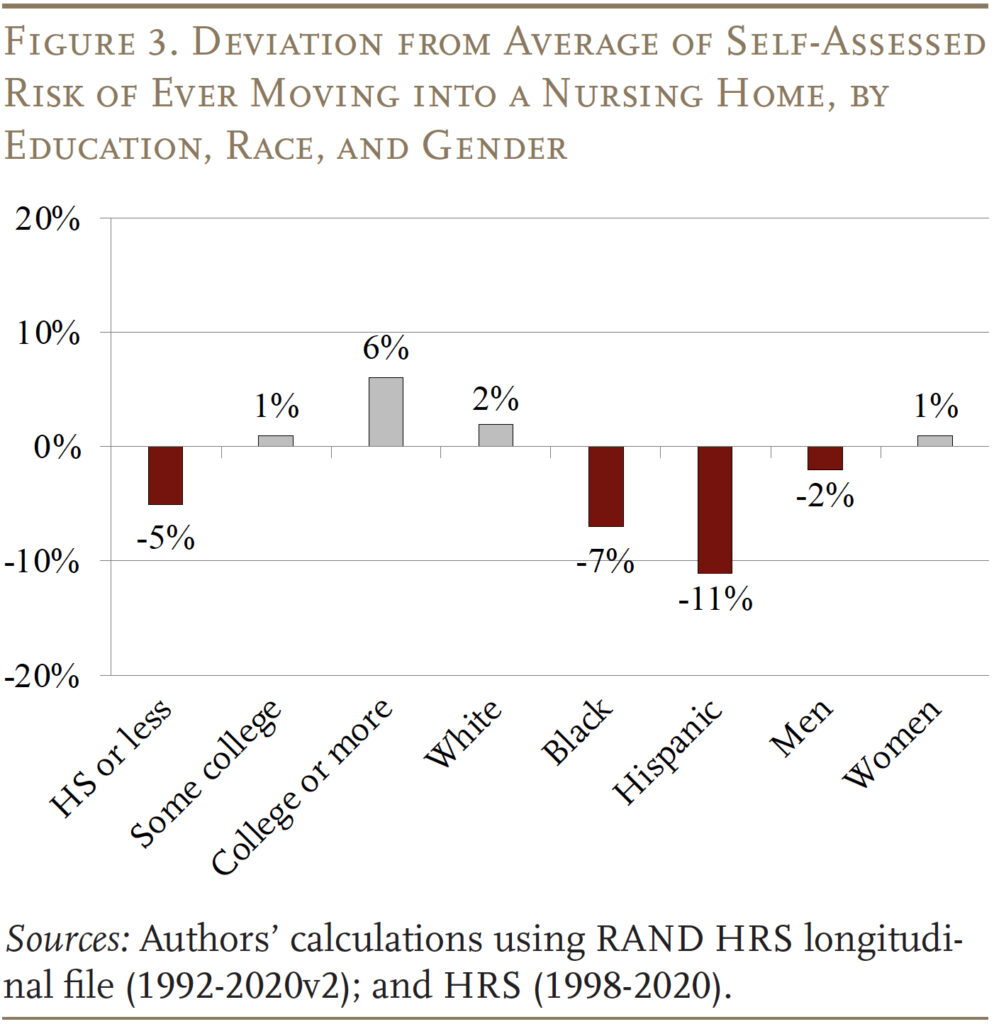

While the HRS questions are likely not good measures of older households’ perceived high-intensity future needs, the variation in responses by demographics provides some useful insights. In terms of ever moving into a nursing home, Blacks, Hispanics, and those with a high school degree or less perceive their risks to be substantially below average (see Figure 3). As noted earlier, these groups face a higher likelihood of needing high-intensity LTC.

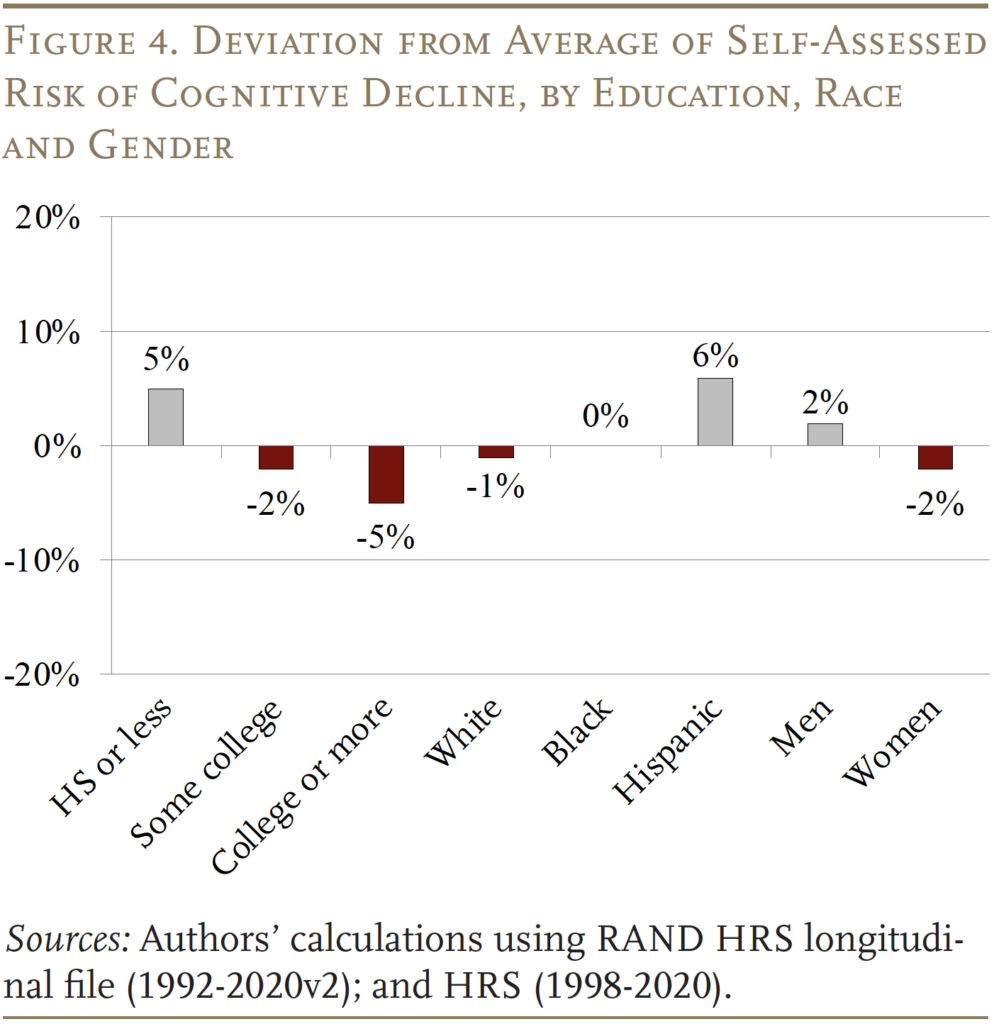

In terms of cognitive decline, assessments are generally more uniform across groups, but women and those with at least some college are more sanguine about needing help than others (see Figure 4). Women are slightly more optimistic despite the fact that they have a higher-than-average risk.

Conclusion

This brief examined two measures of self-assessed LTC risks along with objective probabilities of ending up with high-intensity care needs. The results indicate that neither of the self-assessed measures are good proxies for capturing self-assessed high-intensity needs. However, looking at the demographic breakdowns for the self-assessments does provide some useful insights. Specifically, Blacks and Hispanics may be underestimating their risks of future LTC needs. And while women seem to be aware of average LTC risks, they may not realize that they face higher-than-average risks of needing care. In short, the groups that have a higher probability of high-intensity needs as they age also have fewer resources to provide for their care.

It is important to note that even being aware of LTC risks does not equate to being financially prepared to handle the costs of providing high levels of care. But, a first step in being prepared is understanding the extent to which these risks exist. Future research could design questions that better capture older adults’ perceived LTC risks.

References

Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. 2015. “Long-Term Care in America: Americans’ Outlook and Planning for Future Care.” Chicago, IL.

Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. 2021. “Long-Term Care in America: Americans Want to Age at Home.” Chicago, IL.

Belbase, Anek, Anqi Chen, and Alicia H. Munnell. 2021a. “What Level of Long-Term Services and Supports Do Retirees Need?” Issue in Brief 21-10. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Belbase, Anek, Anqi Chen, and Alicia H. Munnell. 2021b. “What Resources to Retirees Have for Long-Term Services & Supports?” Issue in Brief 21-16. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Brown, Jeffrey R., Gopi Shah Goda, and Kathleen McGarry. 2012. “Long-term Care Insurance Demand Limited by Beliefs about Needs, Concerns about Insurers, and Care Available from Family.” Health Affairs 31(6): 1294-1302.

Chen, Anqi, Alicia H. Munnell, and Nilufer Gok. 2025. “Do Households Have a Good Sense of Their Long-Term Care Risks?” Working Paper 2025-1. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Finkelstein, Amy and Kathleen McGarry. 2006. “Multiple Dimensions of Private Information: Evidence from the Long-term Care Insurance Market.” American Economic Review 96(4): 938-958.

Henning-Smith, Carrie E. and Tetyana P. Shippee. 2015. “Expectations About Future Use of Long-Term Services and Supports Vary by Current Living Arrangement.” Health Affairs 34(1): 39-47.

Hinton, Ladson, Duyen Tran, Kate Peak, Oanh L. Meyer, and Ana R. Quiñones. 2024. “Mapping Racial and Ethnic Healthcare Disparities for Persons Living with Dementia: A Scoping Review.” Alzheimer’s & Dementia 20 (4): 3000-3020.

Johnson, Richard. 2019. “What Is the Lifetime Risk of Needing and Receiving Long-Term Services and Supports?” Research Brief. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Khatutsky, Galina, Joshua M. Wiener, Angela M. Greene, and Nga T. Thach. 2017. “Experience, Knowledge, and Concerns about Long-Term Services and Supports: Implications for Financing Reform.” Journal of Aging & Social Policy 29(1): 51-69.

LIMRA. 2022. “Do Consumers Really Understand Long-Term Care Insurance?” News Release (November 15). Windsor, CT.

Lin, Pei-Jung, Allan T. Daly, Natalia Olchanski, Joshua T. Cohen, Peter J. Neumann, Jessica D. Faul, Howard M. Fillit, and Karen M. Freund. 2022. “Dementia Diagnosis Disparities by Race and Ethnicity.” Medical Care 59(8): 679-686.

Pauly, Mark V. 1990. “The Rational Nonpurchase of Long-Term-Care Insurance.” Journal of Political Economy 98(1): 132-168.

RAND. Health and Retirement Study Longitudinal File, 1992-2020v2. Santa Monica, CA.

Robison, Julie, Noreen Shugrue, Richard H. Fortinsky, and Cynthia Gruman. 2013. “Long-Term Supports and Services Planning for the Future: Implications from a Statewide Survey of Baby Boomers and Older Adults.” Edited by John B. Williamson. The Gerontologist 54(2): 297-313.

Spillman, Brenda C., Jennifer Wolff, Vicki A. Freedman, and Judith D. Jasper. 2014. “Informal Caregiving for Older Americans: An Analysis of the 2011 National Study of Caregiving.” Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

Swaddiwudhipong, Nol, David J. Whiteside, Frank H. Hezemans, Duncan Street, James B. Rowe, and Timothy Rittman. 2023. “Pre-diagnostic Cognitive and Functional Impairment in Multiple Sporadic Neurodegenerative Diseases.” Alzheimer’s & Dementia 19(5): 1752-1763.

University of Michigan. Health and Retirement Study, 1992-2020. Ann Arbor, MI.

Endnotes

- Chen, Munnell, and Gok (2025). ↩︎

- ADLs include: bathing, eating, walking, toileting, getting in/out of bed, and getting dressed. Studies on the intensity of LTC needs among the elderly have found three types of people: 1) those who need support with only IADLs (e.g., shopping, preparing meals) are considered to have low-intensity needs; 2) those with one ADL have medium-intensity needs; and 3) those with 2+ ADLs or dementia have high-intensity needs. These definitions are consistent with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) requirements and prior literature. See Spillman et al. (2014) and Johnson (2019). ↩︎

- LIMRA (2022) estimates that only 3 percent of Americans have long-term care insurance. ↩︎

- Much of the work on subjective LTC risks is from the perspective of whether individuals’ perceptions influence decisions on buying LTC insurance (Pauly 1990; Brown, Goda, and McGarry 2012; and Finkelstein and McGarry 2006). The limitation is that very few people buy LTC insurance. Others, such as Henning-Smith and Shippee (2015), have examined characteristics associated with LTC risks, but they do not compare self-assessments with objective measures of risk. While some surveys ask respondents whether they think they will ever need LTC, few distinguish between the different levels of care, and almost none are able to compare self-assessed risks with actual risks. See Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research (2015), Robison et al. (2013), and Khatutsky et al. (2017). ↩︎

- Finkelstein and McGarry (2006). ↩︎

- The focus is on those with high-intensity needs that last more than 90 days for two reasons. First, many people who will need high-intensity care for short periods of time – e.g., after a knee or hip replacement – are not counted because those instances do not impact their long-term quality of life. Second, from a financing perspective, Medicare covers skilled-nursing-home stays after an acute event (such as surgery), limiting the out-of-pocket costs for families. ↩︎

- For more details, see the full paper (Chen, Munnell, and Gok 2025). ↩︎

- Between ages 75-79 respondents are told to assume they are still alive at age 90, between ages 80-84 they are told to assume they are still alive at age 95, and between 85-90 to assume they are still alive at 100. ↩︎

- A limitation of this approach is that the two expectation questions are not asked of respondents of the same age. The average age at which respondents are asked about their perception of ever needing nursing home care is around 55 compared to 67 for the question regarding severe cognitive limitations. Thus, it is not really possible to compare the subjective questions with each other, but they are the best questions available for determining how pre-retirees and young retirees assess their own risks for needing high-intensity LTC as they age. ↩︎

- An AP-NORC survey on long-term care found that 76 percent of Americans prefer to receive care in their home and 66 percent are moderately or very concerned about losing their independence as they get older (Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research 2021). ↩︎

- Recent studies have found that dementia can occur up to nine years before official diagnosis (Swaddiwudhipong et al. 2022) and Alzheimer’s and dementia diagnoses are more likely to be missed or delayed among Blacks and Hispanics so they may be underdiagnosed (Hinton et al. 2024 and Lin et al. 2022). ↩︎