A Social Security Payroll Tax Increase Should Be Part of the Solution

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

But the increase should be small and gradual.

Enough with politics. It’s time to get back to solving problems. Not surprisingly – given my slant on the world – the problem I care most about is fixing Social Security. But in an attempt to protect lower-income households, President Biden committed to never raising taxes on households earning less than $400,000. This prohibition turned reasonable plans for a comprehensive solution into silly proposals where benefit expansions would sunset after a few years.

My view is that a modest increase in the payroll tax rate should be part of any package to close Social Security’s 75-year shortfall. Indeed, the Social Security actuaries’ scoring of options shows that very gradually increasing the employee and employer payroll tax rate each by 1 percentage point (from 6.2 percent today to 7.2 percent in 2049) would cut the 75-year deficit from 3.5 percent of taxable payroll to 1.5 percent. Of course, other components would be required, such as raising the taxable earnings base, expanding coverage to state and local workers, and perhaps investing some trust fund reserves in equities. And if 1 percentage point is too much of a payroll tax increase, then cut it in half. But some increase in the rate should at least be open for discussion.

But it hasn’t been discussed because of the pledge of no new taxes for those earning less than $400,000. The question that perplexes me is where this cutoff came from. It reminds me of the 2012 election cycle when both President Obama and then Governor Romney adopted $250,000 for defining the middle class. President Obama proposed to retain the Bush tax cuts for households with less than $250,000 and eliminate the tax cuts for those above the threshold. Romney in an ABC interview offered the same definition of the middle class: “…middle income is $200,000 to $250,000 and less.” Politicians seem to have a mental picture that the middle class can be characterized as having hundreds of thousands of dollars of income.

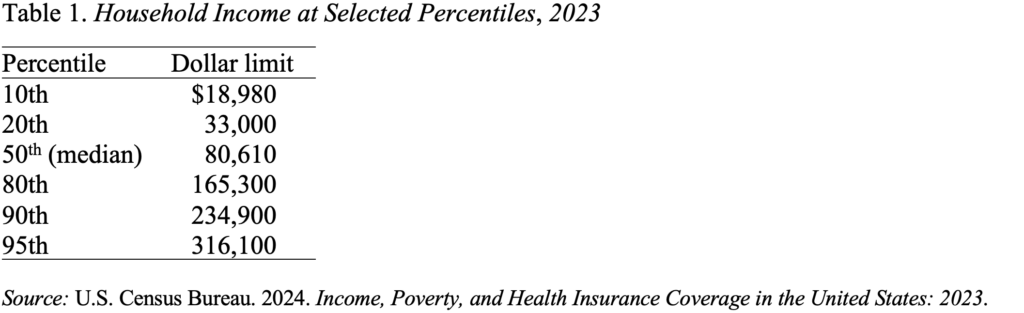

According to the Census data in Table 1, which presents thresholds for being in different parts of the income distribution, the household in the middle of the income distribution in 2023 had an income of $80,610. A household with an income of $316,100 was at the 95th percentile. The thresholds must be interpreted with caution because households include old and young, urban and rural, coastal and midland, and small and large. That said, it is very hard to understand how one could commit to protecting all but the top 5 percent from tax increases.

I’m convinced that the rich in this country do not pay their fair share. But the way to solve that problem is to tax carried interest for those in private equity at full rates, to eliminate the step up in basis at death, to maybe introduce an inheritance tax, etc. Precluding any increase in taxes for the “bottom” 95 percent doesn’t seem sensible to me. And such a commitment makes it all that much harder to solve Social Security’s financing problem.