A Strong Year for 401(k) Balances Masks the Truth About Long-Term Performance

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Meaningful balances require continuous coverage and for that we need a national mandate.

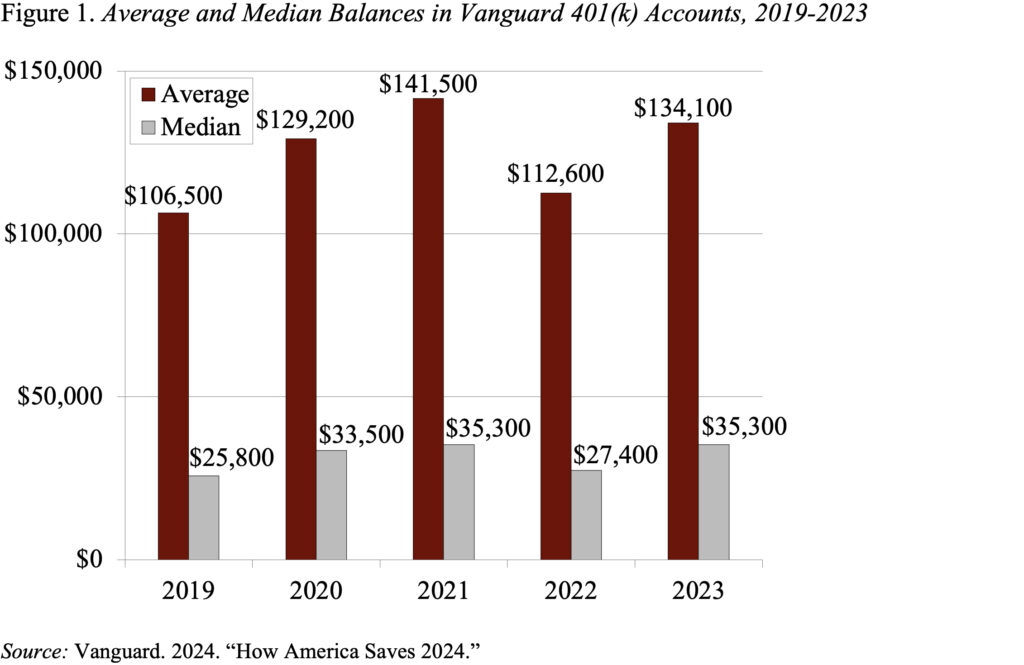

It’s always interesting to look at Vanguard’s most recent edition of “How America Saves.” And it’s particularly interesting to get the numbers for 2023 – a good year for both the economy and the stock market. Indeed, participation rate, contribution rates, and median and average balances are close to an all-time high.

Average balances rose from $112,600 in 2022 – a terrible year for the stock market – to $134,100 in 2023, and median balances from $27,400 in 2022 to $35,300 in 2023 (see Figure 1). The big difference between the median and the average is due to a small number of accounts that have really big balances. Average balances are more typical of long-tenured, more affluent participants, while the median represents the typical participant.

The good performance of all the indicators in 2023, however, does not mean all is well. Balances are actually pretty puny. Consider the holdings of those approaching retirement – ages 55-64. As one would expect, these balances are much larger than those for the full participant population. But still, the median is only $87,600, which means that half of participants have less than this amount and half have more. Moreover, Vanguard tends to administer larger plans, so the plans are better designed than average and participants have higher incomes. In other words, it presents the best face of the 401(k) system.

On the other hand, the balances at any single company do not provide a complete picture of retirement preparedness. First, when participants change jobs, their 401(k) accounts may remain with their old employer, so individuals may have more than one 401(k) account. Second, 401(k) balances are often rolled over to an IRA, and financial services companies cannot track combined 401(k)/IRA holdings. Third, by necessity, balances are provided on an individual, rather than a household, basis. While a complete picture only emerges from household surveys, the Vanguard report always provides interesting information on trends.

And the trends should be good, because a number of changes have improved the functioning of 401(k) plans. Almost 60 percent of the Vanguard plans now have auto-enrollment; target-date funds are now virtually the universal default investment; and fees have declined markedly. Despite these improvements, however, the longer-term picture is not encouraging – particularly once one accounts for inflation.

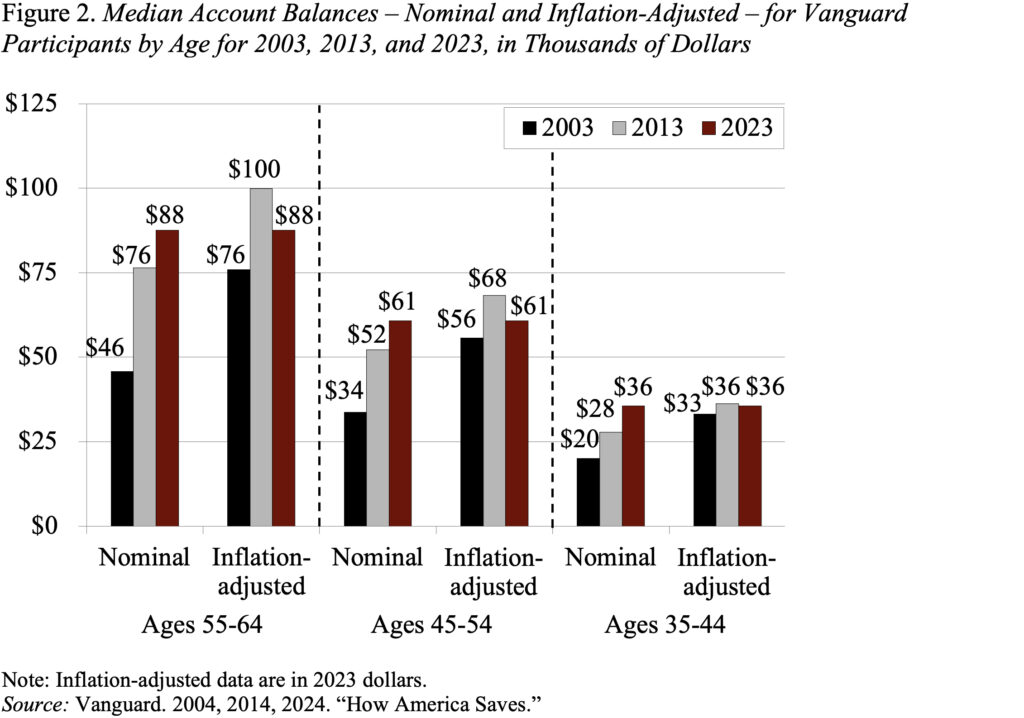

Figure 2 shows balances by age for three years – 2003, 2013, and 2023 – for three different age groups – 55-64, 45-54, and 35-44. Starting first with the pre-retirees – in nominal terms, 2023 balances of $88,000 were higher than balances in 2013 and almost double those in 2003. But taking inflation into account produces a quite different picture – 2023 balances were only slightly higher than those in 2003 and actually lower than the 2013 number. The pattern for younger groups is similar – rising nominal balances over time, but roughly flat balances once the numbers are adjusted for inflation.

In my view, the industry and policymakers have done everything they can to make the 401(k) system work as effectively as possible. As a result, people who are continuously covered by 401(k) plans can and do amass substantial amounts of money. But the typical worker, who moves in and out of coverage, cannot. In real terms – adjusted for inflation – 2023 balances for the typical participant in each age group are below what they were in 2013. No system can work effectively without continuous coverage, and that goal will only be achieved with a national mandate that provides for automatic workplace savings for everyone.