“Alternative Work Arrangements” Now 16 Percent of Workforce

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Increasing numbers are now on their own for health insurance and retirement saving.

Increasingly, commentators refer to the “gig economy,” suggesting that large numbers of workers get a series of short-term jobs through a mobile-app arrangement. Larry Katz (Harvard) and Alan Krueger (Princeton) designed a questionnaire to provide the first nationally representative survey-based estimate of the percentage of the workforce engaged in gig-type activity. They found that only 0.5 percent of all workers identify customers through an online intermediary such as Uber. In the process, however, they uncovered a much more profound shift in the U.S. workforce.

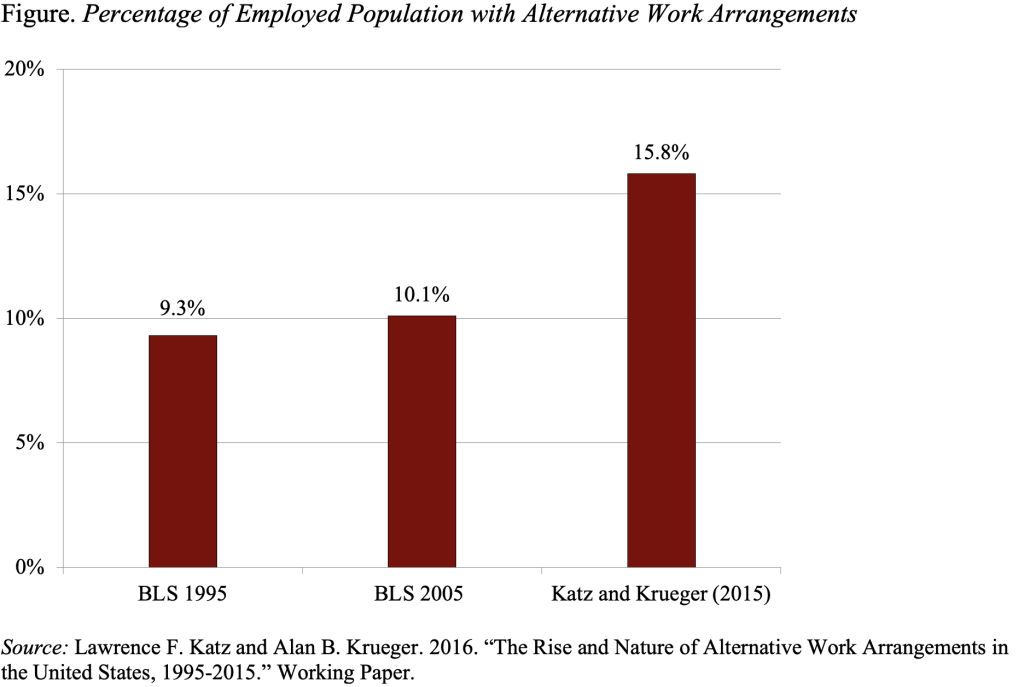

Updating the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) Contingent Work Survey, which the agency has been unable to conduct since 2005, the researchers found that the percentage of workers engaged in alternative work arrangements – defined as temporary help agency workers, on-call workers, contract company workers, and independent contractors – rose from 10.1 percent in 2005 to 15.8 percent in late 2015. This increase is dramatic given that the BLS survey showed virtually no change between 1995 and 2005 (see Figure).

The fact that a growing group of workers does not have a traditional employer/employee relationship has enormous implications. In the United States, most forms of insurance are provided through the workplace. If workers have no employer, they have no one to contribute towards worker compensation in the event they are injured or unemployment insurance in the event they lose their job. Even more important, these individuals with alternative work arrangements are not automatically provided health insurance, albeit the Affordable Care Act has made it easier for them to acquire health insurance through an exchange.

To someone like me with a laser-like focus on retirement, the most obvious and serious loss for this 16 percent of the workforce is that they are not enrolled in a retirement plan. And the evidence clearly indicates that people do not go out and open up an Individual Retirement Account on their own. Moreover, I’m afraid that these people with alternative work arrangements are not going to be picked up by the state savings initiatives underway in California, Connecticut, Illinois, and Oregon. Those initiatives impose a mandate on employers that are not providing a plan to automatically enroll their workers in an IRA. The people with alternative work arrangements do not have an employer. Other routes exist for coverage, but it will not happen without some special effort.

An important question is whether this shift towards alternative work arrangements is a one-time event or the beginning of a trend. The answer depends importantly on why the shift is occurring. On the supply side, Katz and Krueger note that alternative work arrangements are more common among older and more highly educated workers, and the workforce has become older and better educated over time. But this factor, they conclude, explains only 10 percent of the increase. Similarly, people could simply prefer more flexible work arrangements and these arrangements are more feasible in the wake of the ACA, but that increase seems very large as a response to the availability of health insurance outside the workplace.

On the demand side, employers may prefer these new arrangements because they do not have to share profits with the workers. Or more importantly, employers may be responding to technological change, which standardizes job tasks and makes it more feasible for them to hire and monitor contingent workers. All these explanations suggest the trend will continue.

The only argument for a one-shot event is that the dislocation caused by the Great Recession forced workers to accept other arrangements when traditional jobs were not available.

We will know more in 2020. If the government does not have the funding to undertake the survey (a ridiculous state of affairs!), I hope that Katz and Krueger update their important study.