Social Security Needs More Money or Benefits Will Be Cut

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

75-year deficit remains, exhaustion of trust fund isn’t far away.

The 2017 Social Security Trustees Report repeats the drumbeat that the program faces a deficit equal to 2.83 percent of payroll over the next 75 years and that its trust fund is scheduled for exhaustion in the early 2030s.

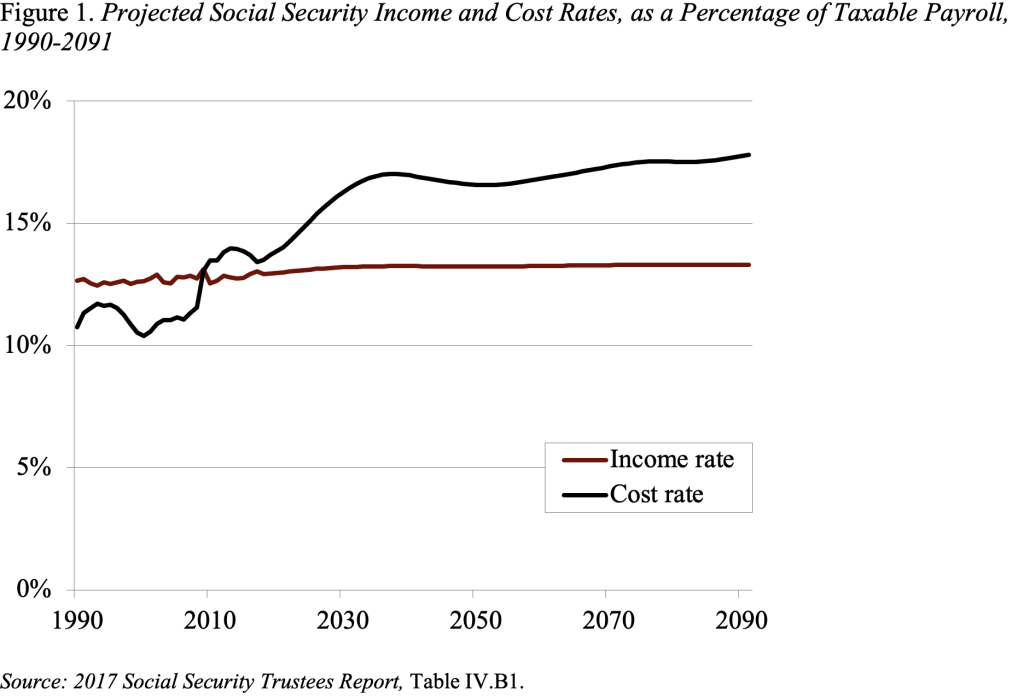

The 75-year deficit is the result of a constant tax rate and increasing costs. The increase in costs is driven by the demographics, specifically the drop in the total fertility rate after the baby-boom period. The combined effects of a slow-growing labor force and the retirement of baby boomers reduce the ratio of workers to retirees from 3:1 to 2:1 and raise costs commensurately (see Figure 1).

The 75-year deficit is the difference between the present discounted value of scheduled benefits and the present discounted value of future taxes plus the assets in the trust fund. This calculation shows that Social Security’s long-run deficit is projected to equal 2.83 percent of covered payroll earnings. That figure means that if payroll taxes were raised immediately by 2.83 percentage points – 1.42 percentage points each for the employee and the employer – the government would be able to pay the current package of benefits for everyone who reaches retirement age through 2091, with a one-year reserve at the end.

The 75-year cash flow deficit is mitigated somewhat by the existence of a trust fund, with assets currently equal to roughly three years of benefits. These assets are the result of cash flow surpluses that began in response to reforms enacted in 1983. The program, however, is currently using interest on these assets and will soon be drawing on the assets themselves to cover annual benefit payments. The trust fund is projected to be exhausted in 2034.

The exhaustion of the trust fund does not mean that Social Security is “bankrupt.” Payroll tax revenues keep rolling in and can cover about 75 percent of currently legislated benefits over the remainder of the projection period. Relying on only current tax revenues, however, means that the replacement rate – benefits relative to pre-retirement earnings – will drop to a level not seen since the 1950s.

The bottom line is that we are going to have to either come up with more money or cut Social Security benefits by 2034. Two recent proposals provide “bookends” for the range of possibilities. Representative Sam Johnson (R-TX), Chairman of the House Ways and Means Social Security Subcommittee, solves the financing problem by cutting benefits, and Representative John Larson (D-CT), Ranking Member of that Subcommittee, by raising taxes. It is very hard to make any progress without a sense of the desired mix of tax increases and benefit cuts. Do the American people want 100 percent with benefit cuts, 100 percent with tax increases, 50 percent/50 percent, 75 percent/25percent, or 25 percent/75 percent? We need some mechanism to provide Congress with guidance.