Anger over Social Security Financial Problems

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Being new to the blog business, I was never sure if anyone was on the receiving end of my missals. Any uncertainty has been eliminated by an avalanche of angry messages over the weekend in response to “Social Security: The Cheapest Annuity in Town.” The responses to the proposal for households to use existing funds for support and delay claiming Social Security was met with two responses. The first was that Social Security may not be there, so why not grab benefits as soon as possible. The second was that people could not be sure that they will live long enough to make up for foregoing benefits at a younger age. This post will address the first issue. Next week’s will address the second.

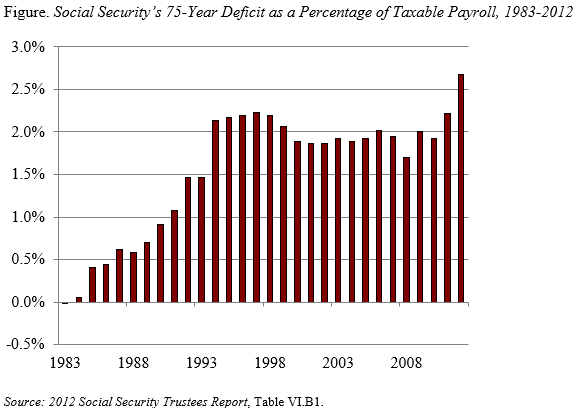

The anger over whether Social Security will be able to pay future benefits is perfectly justifiable. We have known that the program faces long-run financing issues since immediately after the 1983 amendments and that the shortfall was significant and unlikely to right itself since 1993. The Figure shows that the deficit has hovered around 2 percent of taxable payrolls for almost 20 years. Yet, we have done nothing. As a result, the magnitude of the required changes has gotten bigger and the potential of a sharp drop in benefits has become a real risk.

The absence of action is extremely frustrating since the options for fixing the problem have been known for decades. Social Security is a simple system. It takes in money and pays out benefits. If projected benefits exceed projected revenues plus the assets in the trust fund, either the outflow of benefits must be cut and/or the inflow of revenues must increase. Numerous commissions have contributed to a laundry list of ways to cut benefits or raise taxes. So the problem is not like health care, where the answers for controlling costs are elusive; in the case of Social Security, we know exactly what to do. Reasonable people – Republican or Democrat – could sit down for an hour and come up with a compromise plan.

Just to provide an idea of the magnitude of the required changes, consider a situation where all the adjustments were made by raising the payroll tax. As of the most recent Trustees Report, the payroll tax rate for employee and employer would have to rise by 1.3 percentage points each. Such an increase would enable the government to provide the current package of benefits for everyone who reaches retirement age at least through 2086. A lasting fix would require additional changes. But solving the problem for 75 years would be an excellent down payment towards long-run solvency.

Describing the magnitude of the problem in terms of a tax fix is designed simply to show that the challenge is manageable. Increasing the age of eligibility for full benefits slowly and changing the indexing would reduce the required tax increase.

Who is to blame that, despite the menu of options, no action has been taken? Our political system makes it very difficult for individual politicians to increase taxes 50 years in advance of a projected shortfall. In 1993, trust fund assets were projected to last through 2044. The alternative is to have a commission come up with proposals, and indeed such an arrangement led to the important 1983 amendments. But we have had a lot of commissions, all with detailed proposals for solving the problem, and no action taken. My view is that proposals to privatize a portion of the system served as a major distraction.

At this point, restoring balance to Social Security should be the highest priority. It is easy conceptually; its effects will not be felt until the economy recovers; it would give us a sense that we can manage our fiscal house; and it would restore confidence in the nation’s main retirement program so that people can make good decisions about when to claim benefits.