Any Social Security Legislative Package Should Include an Automatic Adjustment Mechanism

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

There is a backstop, but it’s a draconian one.

When the horse-trading begins on a package to restore financial balance to the Social Security program, one item that should be considered is some form of automatic adjustment mechanism. While the financial implications of the ultimate package will be based on the best assumptions regarding wages, prices, and demographics at the time, these assumptions may not pan out, and the system might once again be heading for deficits. And U.S. policymakers are terrible at addressing Social Security’s financial problems before we are about to fall off a cliff.

The last major piece of Social Security legislation was enacted in 1983 – exactly forty years ago. At that time, the program was within months of being unable to pay full benefits. Today, we face the prospect of a 23-percent benefit cut in 2033 when the assets in the Old Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) trust fund are depleted.

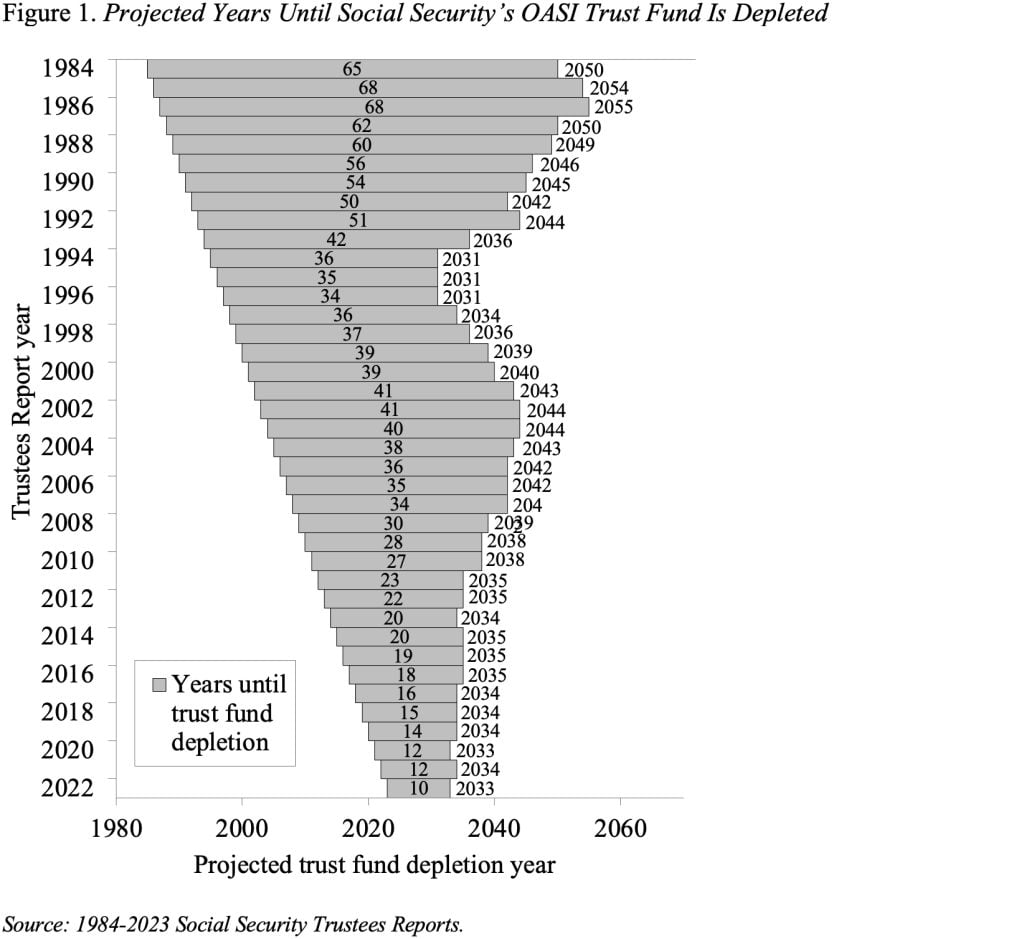

Policymakers have known for decades that the OASI trust fund would be exhausted in the 2030s (see Figure 1) but have taken no action. Not acting has costs. It undermines Americans’ confidence in the backbone of our retirement system and causes some to claim their benefits early, hoping that those on the rolls may be spared future cuts. More importantly, delaying action means the eventual changes must be more abrupt, and fewer generations participate in the fix.

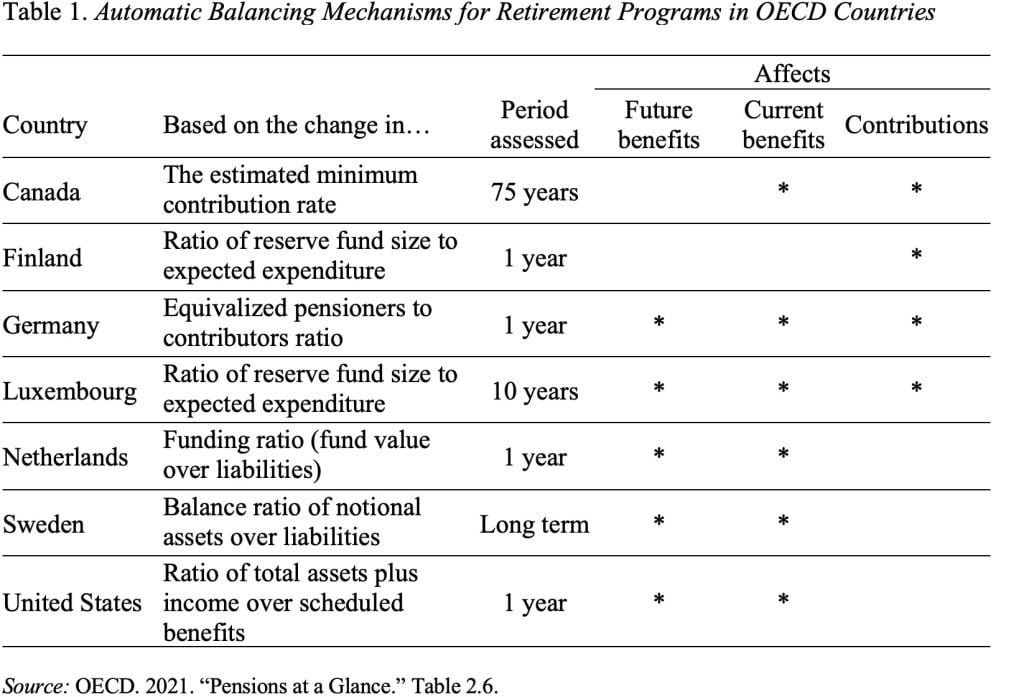

One way to avoid repeated crises and restore confidence in the financial stability of the Social Security program is for any package of solutions to include a mechanism that automatically adjusts revenues or benefits if shortfalls emerge. As of the most recent OECD report on retirement programs, many countries have mechanisms that link the parameters of their programs to changes in either economic or demographic developments, and seven have automatic balancing mechanisms explicitly designed to ensure that the retirement plans are fully financed (see Table 1).

As you can see, the United States is included on this list. We, in fact, do have a mechanism to ensure that the system is fully funded. When the trust fund is depleted, Social Security must cut benefits to the level of incoming revenues – hence, the projected 23-percent benefit cut in 2033. This mechanism is a very draconian way to spur action – and it doesn’t seem very effective, except at creating great anxiety among older workers and retirees.

The Canadians have a much more civilized approach – perhaps one that could serve as a model for the United States. It is a backstop arrangement that is activated only in the absence of a political agreement. Mechanically it works as follows. Every three years, the Chief Actuary estimates the minimum contribution rate needed to finance the system over 75 years. If the required rate exceeds the legislated rate and policymakers cannot agree on a solution, the backstop kicks in. In that case, the cost-of-living adjustment is frozen, and contribution rates are increased by 50 percent of the difference between the legislated and the required rate for three years until the Chief Actuary’s following report. The mechanism thus avoids uncertainty about the system’s financial stability over time if policymakers fail to act.

We don’t have to adopt the specifics of the Canadian backstop mechanism, but including some automatic adjustment in the face of inaction would improve confidence in the long-term stability of our Social Security program.