As the President Proposed, Medicare Needs the Ability to Negotiate Drug Prices

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

One last look at Aduhelm and Medicare.

President Biden, in his State of the Union speech, proposed giving Medicare the ability to negotiate lower prices for prescription drugs. I’m assuming the President means not only over-the-counter drugs covered under Part D but also medications administered in a doctor’s office covered under Part B. Medicare sorely needs that ability. While Medicare’s decision to limit the coverage of Aduhelm to clinical trials will hold costs in check for a while, the bigger issue is the financial implications of an effective drug for early Alzheimer’s in an environment where Medicare has no ability to negotiate prices.

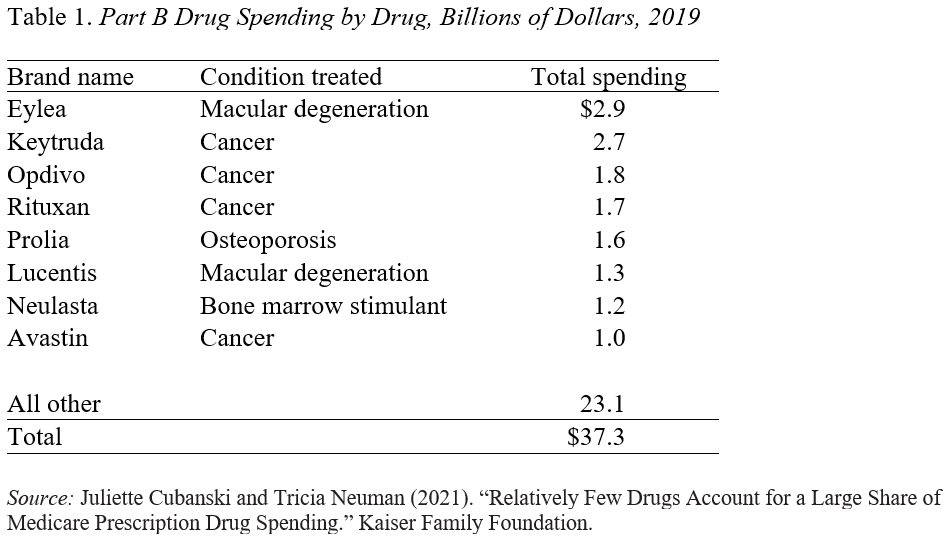

While Biogen originally priced Aduhelm at $56,000, it reduced the price, in response to weak sales, to $28,200. Even at a price of $28,200, with 1 million recipients, Medicare’s bill would have been $23 billion (Medicare pays 80 percent, and beneficiaries pay 20 percent in copayments). Aduhelm expenditures would have amounted to about two-thirds of what Medicare Part B currently spends on all drugs and eight times what it spends on the current most expensive drug – Eylea (see Table 1).

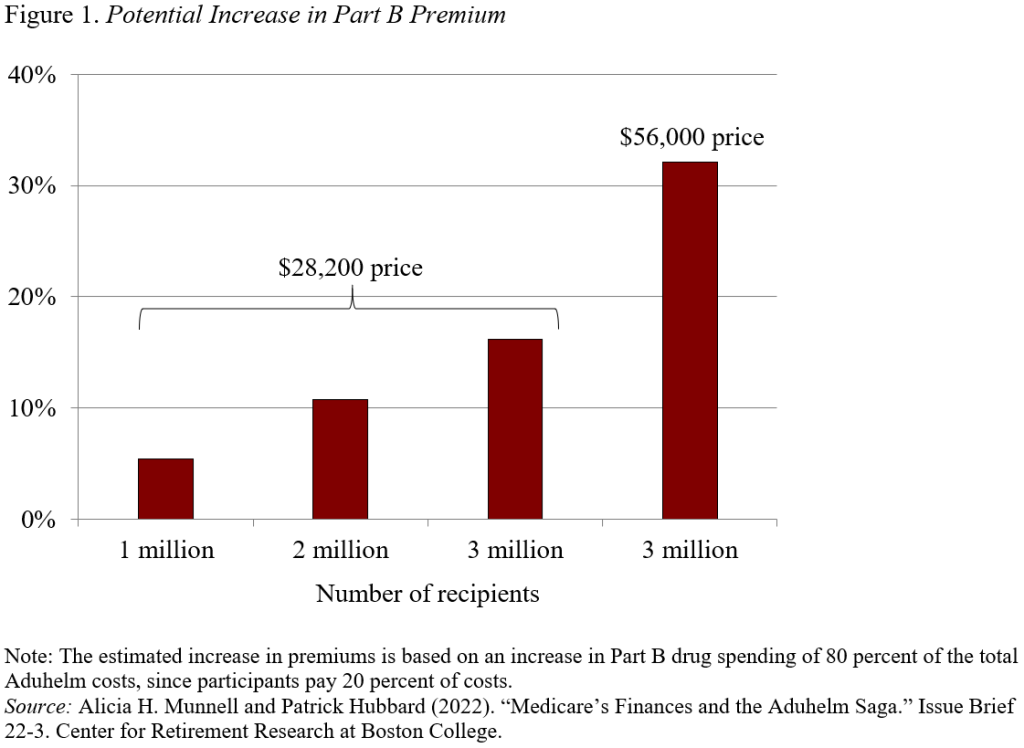

Since total Medicare Part B expenditures in 2020 were $419 billion, a $23-billion increase would require a 5.4-percent increase in Part B premiums. Those costs would rise over time as more and more individuals stricken with Alzheimer’s become eligible. And they could double if a competitor offers a clearly effective product at Biogen’s original price of $56,000. The growing volume of eligible patients and Biogen’s original price could require an eventual 32-percent increase in Part B premiums (see Figure 1).

Alzheimer’s patients would also pay high out-of-pocket costs both for the drug and for related medical services (such as regular MRI scans), since beneficiaries usually pay 20-percent coinsurance. So, even at the “reduced price” of $28,200, beneficiaries would pay $5,640 for one year’s supply of Aduhelm. At the original $56,000 price, the coinsurance would have been $11,200. Traditional beneficiaries without a Medigap policy would face the cost directly; those with a Medigap policy would see their premiums rise; and those in Medicare Advantage plans would also be responsible for cost-sharing until they reached their annual out-of-pocket maximum. All these increased expenditures would be devastating to the typical Medicare beneficiary with an average income of about $30,000. And, as noted, Aduhelm is not a cure, so patients would likely incur these costs for multiple years.

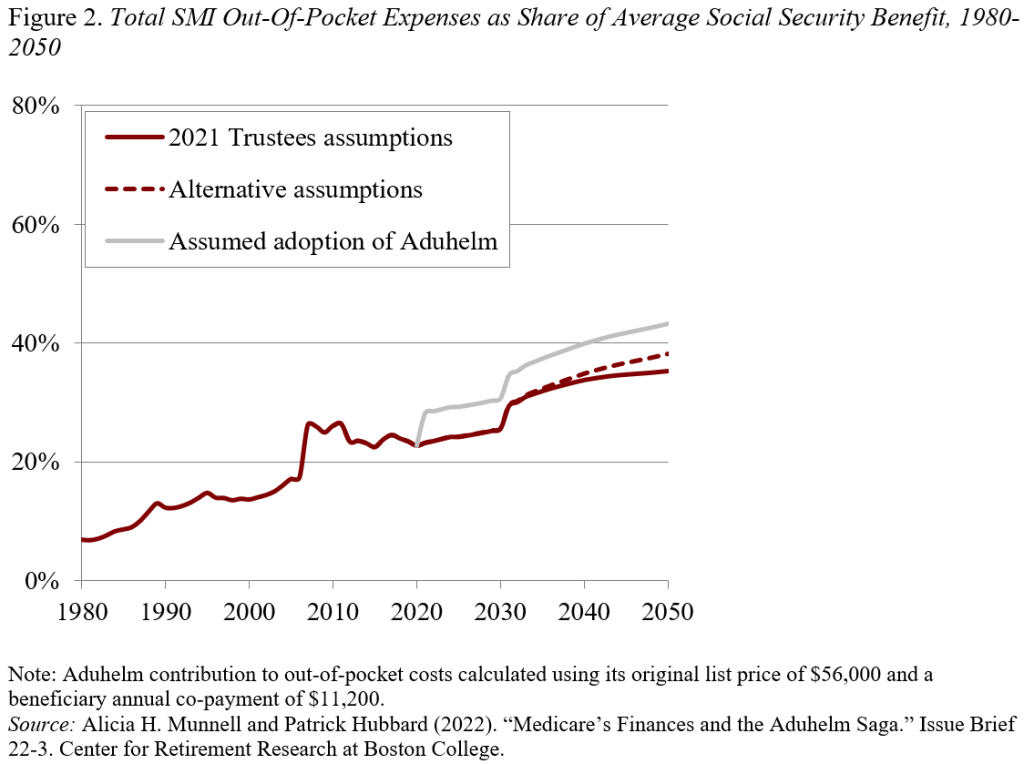

The increase in Part B premiums and coinsurance from Aduhelm would have increased average out-of-pocket costs significantly as a share of the average Social Security benefit. These costs now amount to about 25 percent of the average Social Security benefit, are scheduled to rise to 35 percent by 2050 under the 2021 Trustees assumptions, and to 38 percent under the alternative assumptions (see Figure 2). If Medicare had approved Aduhelm at the original price of $56,000 and 3 million beneficiaries eventually qualified for the drug, the projected out-of-pocket costs would equal 43 percent of the average Social Security benefit by 2050. Of course, at some point patents expire and generics emerge, placing some control over the drug creator’s price.

Clearly, the goal of society is to alleviate the ravages of a dreadful disease, but the Aduhelm saga has highlighted the risk to the system’s finances if a valuable drug should become available and Medicare remains unable to negotiate prices. Hopefully, the Aduhelm saga will rekindle Congressional interest in giving Medicare some authority to negotiate drug prices.