Social Security’s Financial Outlook: The 2023 Update in Perspective

The brief’s key findings are:

- The 2023 Trustees Report showed a slight increase in the 75-year deficit and the depletion of the retirement trust fund moved up to 2033.

- The prospect of a 23-percent benefit cut only 10 years away should focus our attention on restoring balance to the program.

- The “Missing Trust Fund,” a result of paying excess benefits to early generations, provides a strong case for some general revenue financing.

- Workers would contribute the amount required in a funded system, and general revenues would compensate for the “Missing Interest.”

- Thus, the historical burden would be distributed more broadly, but the sense that workers pay for their own benefits would remain.

Introduction

The 2023 Trustees Report slightly increased the 75-year deficit to 3.61 percent of taxable payroll, compared to 3.42 percent in 2022, and moved up depletion of the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) trust fund assets from 2034 to 2033. Yes, the Disability Insurance (DI) trust fund has enough to pay benefits for the full 75-year period and the date of exhaustion for the combined OASDI trust funds is 2034. But combining the two systems would require a change in the law; hence, under current law the relevant date is 2033 – a decade from now.

The fact that in 2033 Social Security would be able to pay only 77 percent of scheduled benefits should focus our collective minds. Thinking of ways to restore balance to the program is not hard; the Social Security Actuaries publish an annual booklet with more than a hundred possible benefits cuts or revenue increases. Indeed, a lot can be said for maintaining a self-financed program. And if the cost of currently scheduled benefits simply exceeds what today’s workers are paying into the system, the traditional proposals to reduce benefits or raise payroll taxes would be most relevant.

However, the cause of the shortfall lies elsewhere. Specifically, the program’s “pay-as-you-go” financing – with the exception of the recent build-up and spend-down of the current modest trust fund – makes the program look expensive. This financing approach is the result of a policy decision in the late 1930s to pay benefits far in excess of contributions for the early cohorts of workers. The decision essentially gave away the trust fund that would have accumulated and, importantly, gave away the interest on those contributions. The “Missing Trust Fund” provides a strong justification for an infusion of general revenues into the program.

This brief updates the numbers for 2023 and emphasizes the need to act to avoid draconian benefit cuts. To that end, it also lays out the case for spreading across all taxpayers – not just today’s workers – the burden associated with giving away the trust fund. If policymakers accepted this rationale for a general revenue infusion, the pathway to eliminating OASI’s 75-year deficit would be much easier. Fixing Social Security sooner rather than later would distribute the burden more equitably across cohorts, restore confidence in the nation’s major retirement program, and give people time to adjust to needed changes.

The 2023 Report

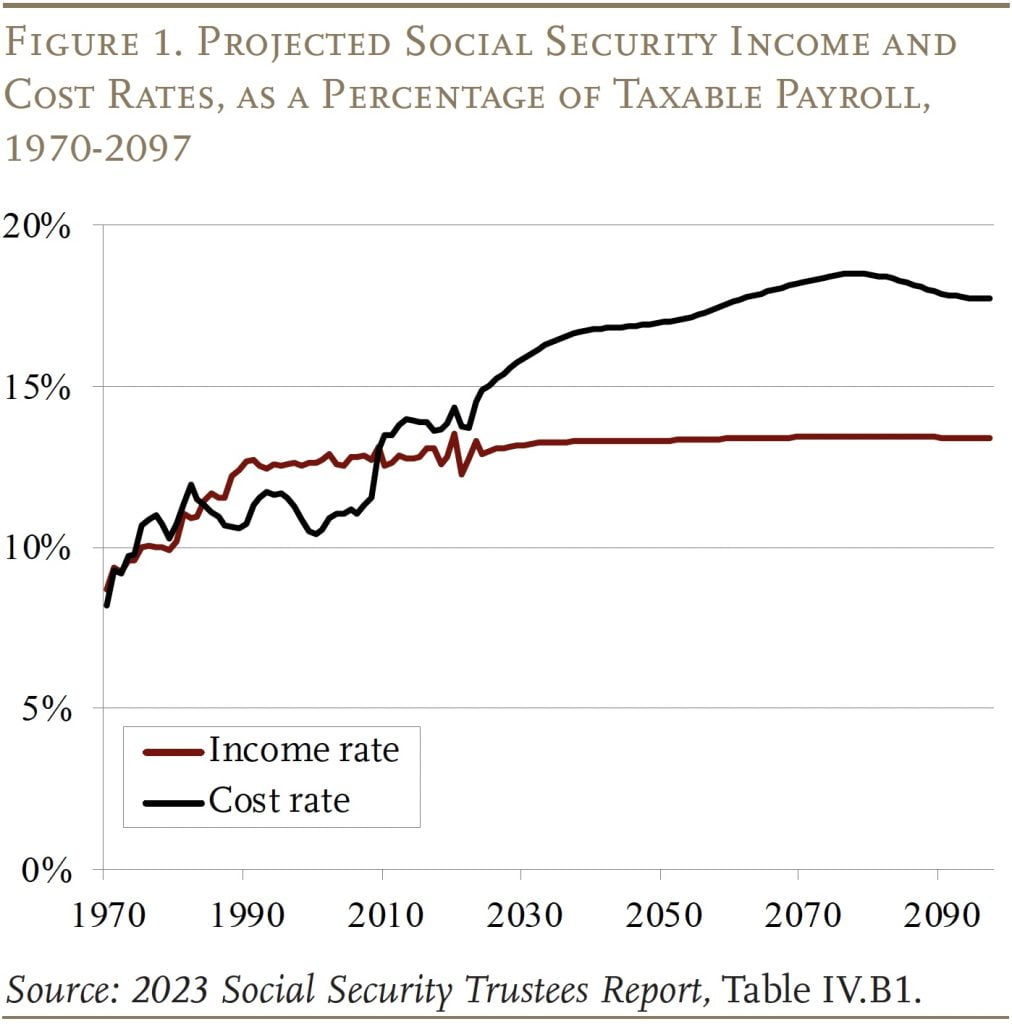

Under the Trustees’ intermediate assumptions, the cost of the OASDI program rises rapidly to about 17 percent of taxable payrolls in 2040, drifts up to about 18.5 percent of taxable payrolls in 2078, and then declines slightly (see Figure 1).

The increase in costs is driven by demographics, specifically the drop in the total fertility rate after the baby boom (those born between 1946 and 1964). Women of childbearing age in 1964 had an average of 3.2 children; by 1974 that number had dropped to 1.8. The combined effects of the retirement of baby boomers and a slow-growing labor force due to the decline in fertility reduce the ratio of workers to retirees from about 3:1 to 2:1 and raise costs commensurately. The increasing gap between the income and cost rates means that the system is facing a 75-year deficit.

The 75-year cash flow deficit is mitigated in the short term by the existence of a trust fund, with assets currently equal to about two years of benefits. These assets are the result of cash flow surpluses due to reforms enacted in 1983. Since 2010, however, when Social Security’s cost rate started to exceed the income rate, the government has been tapping the interest on trust fund assets to cover benefits. And, in 2021, as taxes and interest fell short of annual benefits, the government started to draw down trust fund assets. These drawdowns will continue until the OASI trust fund is depleted in 2033.

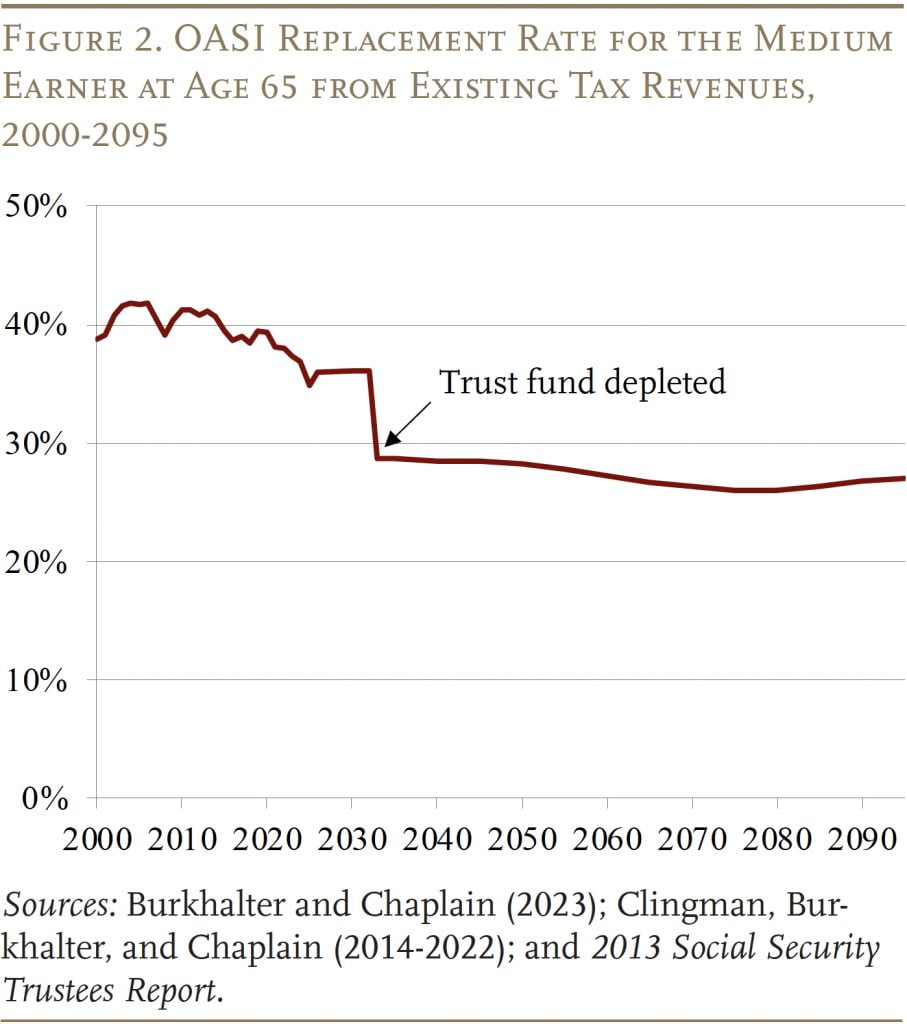

The depletion of the trust fund does not mean that OASI is “bankrupt.” Payroll tax revenues keep rolling in and can cover 77 percent of currently legislated benefits initially, declining to 71 percent by the end of the projection period. Relying only on current tax revenues, however, means that the replacement rate – benefits relative to pre-retirement earnings – for the typical age-65 worker would drop from about 36 percent to about 27 percent – a level not seen since the 1950s (see Figure 2). (Note that the replacement rate for those claiming at 65 has already declined due to the rise in the Full Retirement Age from 65 to 67.)

Moving from cash flows to the 75-year deficit requires calculating the difference between the present discounted value of scheduled benefits and the present discounted value of future taxes plus the assets in the trust fund. This calculation for the OASDI program as a whole shows that Social Security’s long-run deficit is projected to equal 3.61 percent of covered payroll earnings. That figure means that if payroll taxes were raised immediately by 3.61 percentage points – about 1.8 percentage points each for the employee and the employer – the government could pay scheduled benefits through 2097, with a one-year reserve at the end.

At this point, solving the 75-year funding gap is not the end of the story in terms of required tax increases. In the future, once the ratio of retirees to workers stabilizes and costs remain relatively constant as a percentage of payroll, any solution that solves the problem for 75 years will more or less solve the problem permanently. But, during this period of transition, any package of policy changes that restores balance only for the next 75 years will show a deficit in the following year as the projection period picks up a year with a large negative balance. Thus, eliminating the 75-year shortfall should be viewed as the first step toward “sustainable solvency.”1Some commentators cite Social Security’s shortfall over the next 75 years in terms of dollars – $22.4 trillion. Although this number appears very large, the economy will also be growing. So, dividing this number – plus a one-year reserve – by taxable payroll over the next 75 years brings us back to the 3.61 percent-of-payroll deficit discussed above.

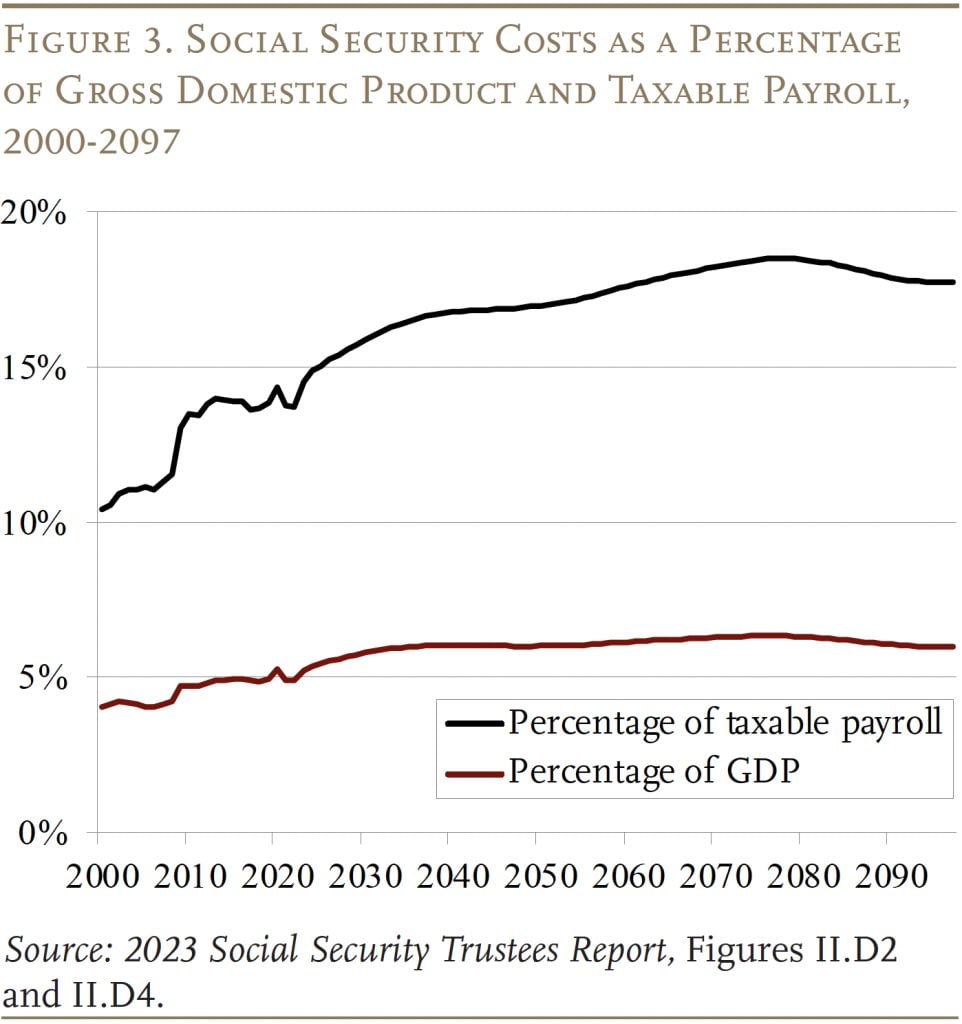

The Trustees also report Social Security’s shortfall as a percentage of GDP. The cost of the program is projected to rise from about 5 percent of GDP today to about 6 percent of GDP as the baby boomers retire (see Figure 3). The reason why costs as a percentage of taxable payroll keep rising – while costs as a percentage of GDP more or less stabilize – is that taxable payroll is projected to decline as a share of total compensation due to continued growth in health benefits.

2023 Report in Perspective

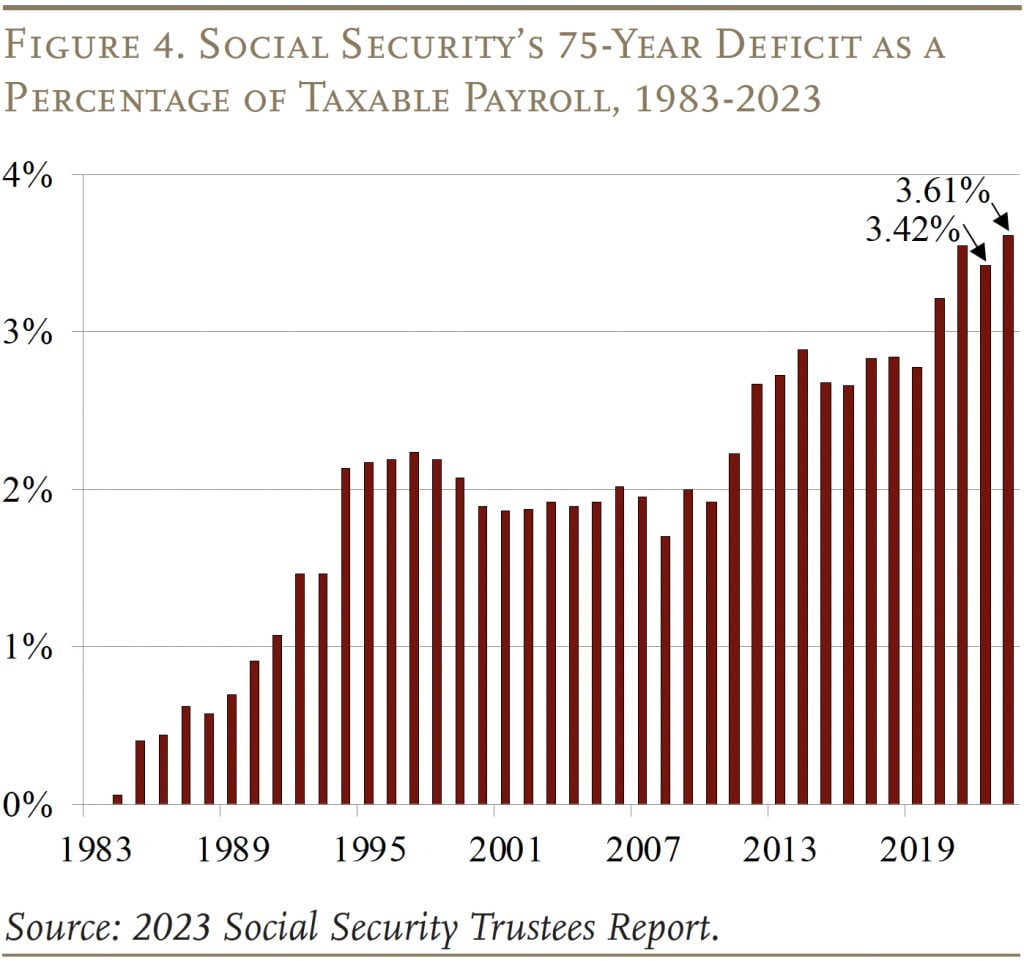

The 75-year deficits in the last three Trustees Reports are the largest since 1983 when Congress enacted major legislation to restore balance (see Figure 4). The main question is why did the deficit grow over the period 1983-2023, and a secondary question is why did it increase since last year’s Report.

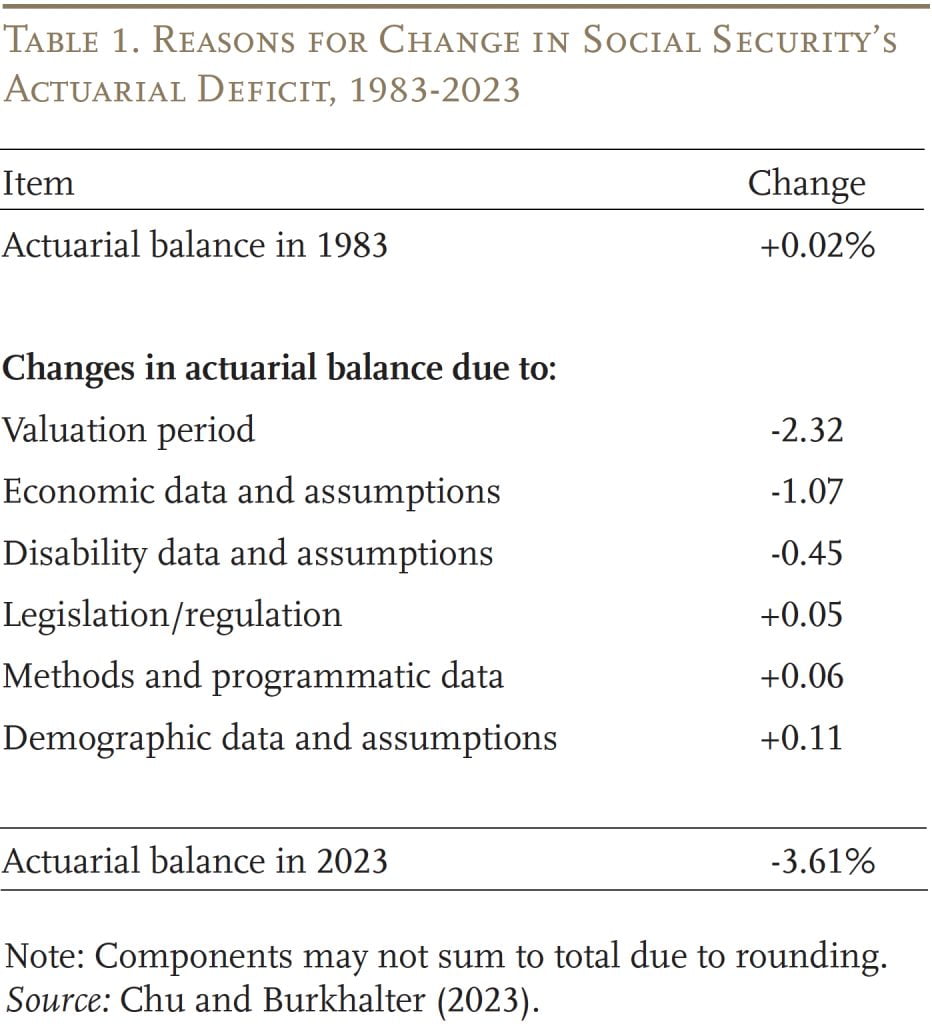

Changes in 75-Year Deficit Since 1983

Social Security moved from a projected 75-year actuarial surplus of 0.02 percent of taxable payroll in the 1983 Report to a projected deficit of 3.61 percent in the 2023 Report. As shown in Table 1, leading the list of reasons is advancing the valuation period. Each time it moves out one year, as noted above, it picks up a year with a large negative balance. The cumulative effect over the last 40 years has been to increase the 75-year deficit by 2.32 percent of taxable payrolls. That is, almost two thirds of the 40-year change in the OASDI deficit is attributable to simply moving the valuation period forward.

A worsening of economic assumptions – primarily a decline in assumed productivity growth and the impact of the Great Recession – have also contributed to the rising deficit. Another contributor over the past 40 years has been increases in disability rolls, although that picture has changed dramatically in recent years.

Partially offsetting the negative factors has been a reduction in the actuarial deficit due to legislative and regulatory changes. Methodological improvements and updated data have also had a positive impact on the system’s finances. The biggest boost has come from changes in demographic assumptions, such as a slower pace of mortality improvement overall. The net effect in 2023 of all these changes is a 75-year deficit equal to 3.61 percent of taxable payrolls.

Changes from Last Year’s Report

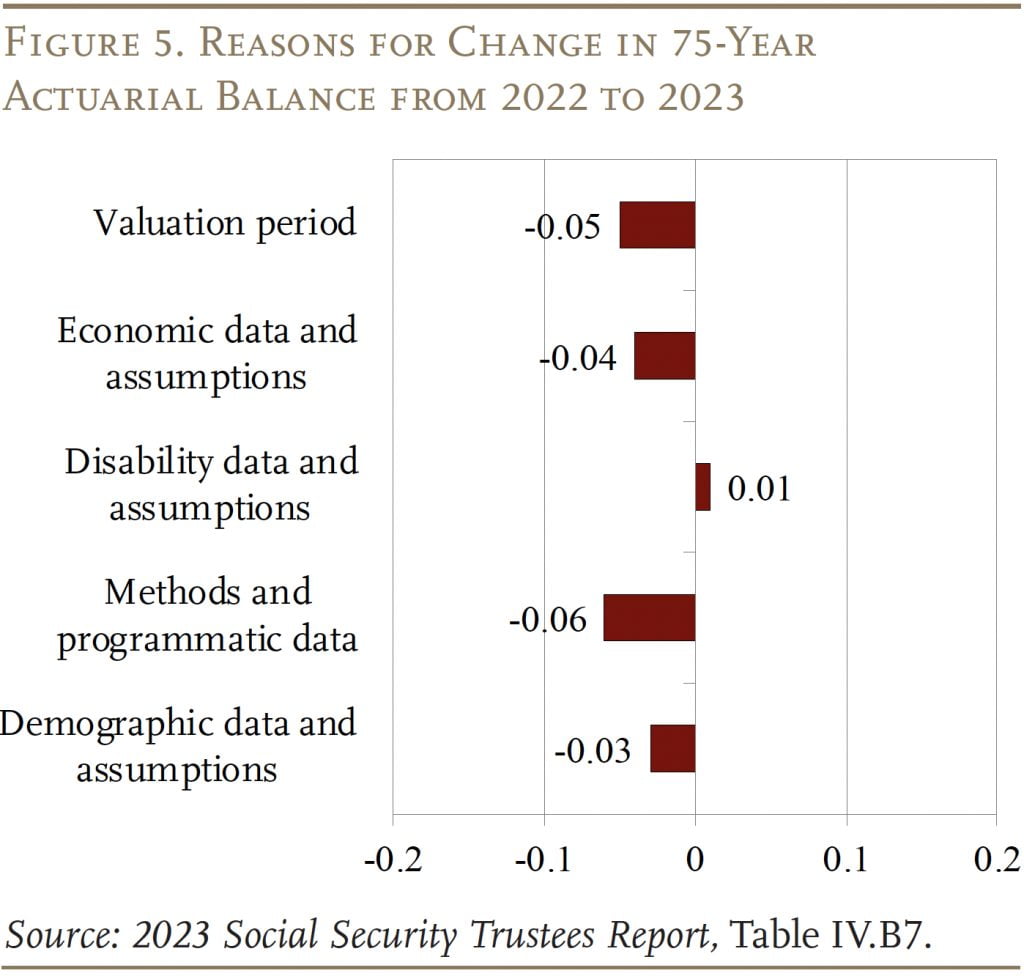

The 3.61 percent of taxable payrolls in the 2023 Report is slightly higher than the 3.42 percent in last year’s Report (see Figure 5). Only three factors allow easy explanations. First, advancing the valuation period to include 2097 alone increased the actuarial deficit by 0.05 percent. Second, in response to higher-than-expected inflation and lower-than-expected output growth, the Trustees revised down the levels of GDP and labor productivity by about 3 percent by 2026 and for all years thereafter. Some other factors had offsetting effects. Third, a continued reduction in assumed DI incidence rates improved the outlook. The remaining two components – methods and programmatic data and demographics – are the net result of a host of small changes. The focus here, however, is not year-to-year changes but rather the upcoming exhaustion of the OASI trust fund.

An Action-Forcing Event and the Case for Some General Revenue Financing

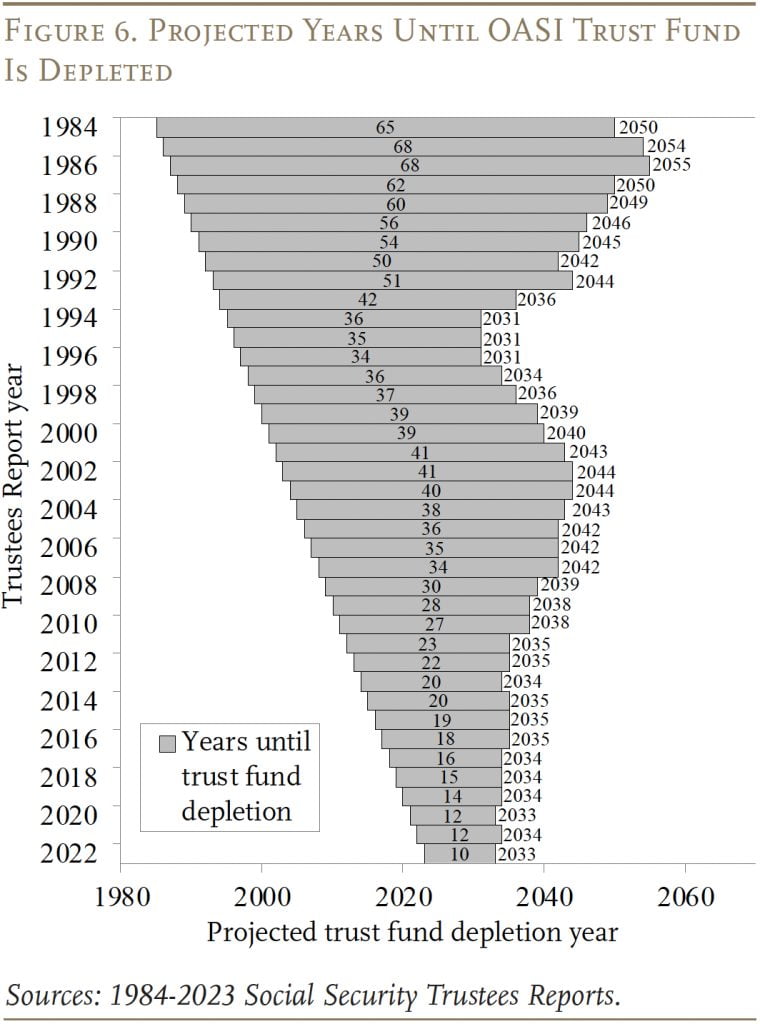

The depletion of the OASI trust fund is not news. Virtually since the year the trust fund began accumulating assets, the Trustees have projected its demise. The point is that the window of opportunity to restore balance has narrowed dramatically over time. Whereas we used to have 68 years to figure out how to avoid trust fund depletion, that number has dropped to 10 years (see Figure 6). If nothing is done before depletion, benefits for all current and future retirees will have to be cut immediately.

The impending depletion of trust fund assets is the ideal time to rethink the program’s financing structure and to consider whether a general-revenue component might be appropriate. The rationale for general revenue is that Social Security costs are high, not because the program is particularly generous, but because the trust fund is missing. If policymakers choose to maintain Social Security benefits at current-law levels, little rationale exists for placing the entire burden of the Missing Trust Fund on today’s workers through higher payroll taxes; that component could be financed more equitably through the income tax.

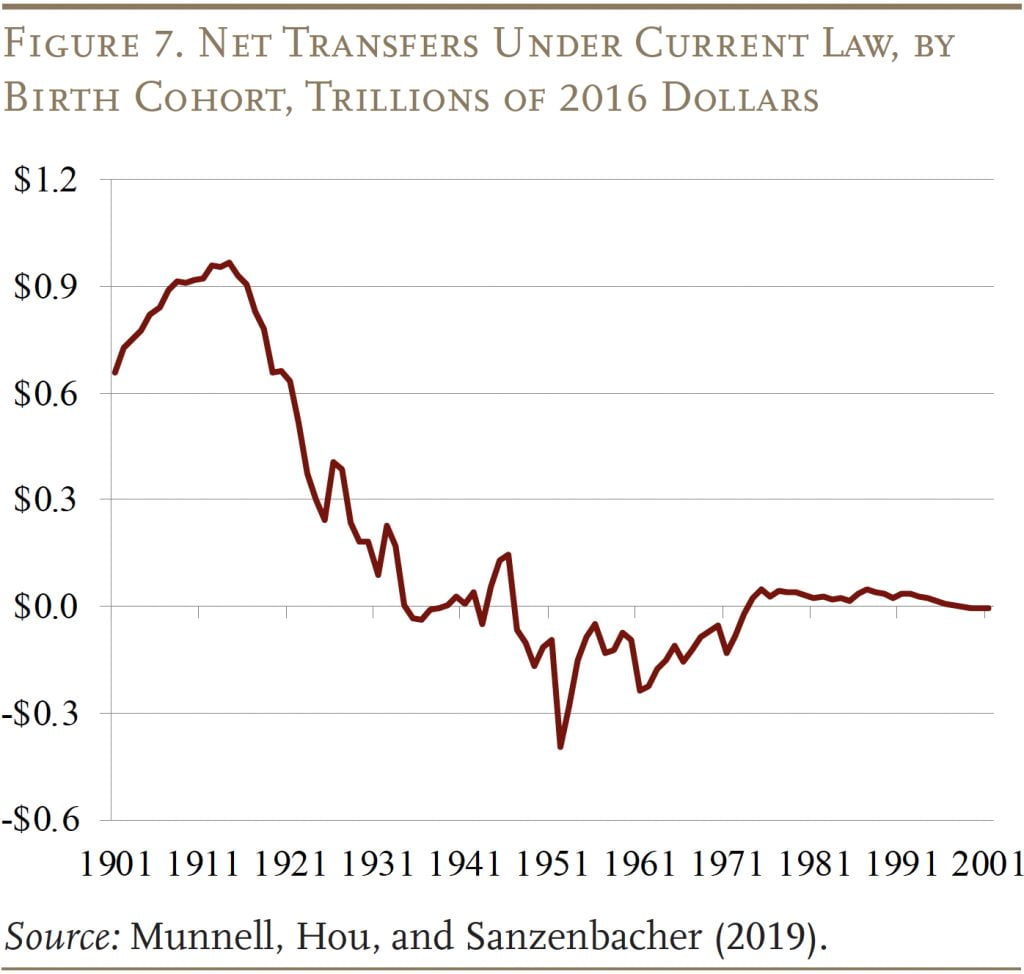

What happened to the trust fund? The Missing Trust Fund consists of two components: 1) benefits paid to early cohorts in excess of their contributions; and 2) net transfers by subsequent birth cohorts. The first part is often referred to as the Legacy Debt. It is not identical to the Missing Trust Fund, because later birth cohorts could have replaced some of that missing fund if they had contributed more into the program than they are projected to receive, or they could have added to the deficit. Figure 7 illustrates that early birth cohorts received large positive transfers – creating a massive legacy debt – and that the net negative transfers experienced by the 1935-2001 birth cohorts only slightly reduced the Legacy Debt. Thus, the Legacy Debt and Missing Trust Fund are very close in value.

The big transfer to early generations was not anticipated in the 1935 legislation, which set up a scheme more similar to a private retirement plan, with the accumulation of a trust fund and the close alignment of contributions and benefits. The 1939 amendments, however, fundamentally changed the nature of the program. These amendments tied benefits to average earnings, initially over a minimum period of coverage, and added spousal and survivor benefits that were effectively unfunded, thus breaking the link between lifetime contributions and benefits. As a result, in the early stages of the program, payroll tax receipts were used to pay benefits to retirees far in excess of their contributions rather than to build up a trust fund.

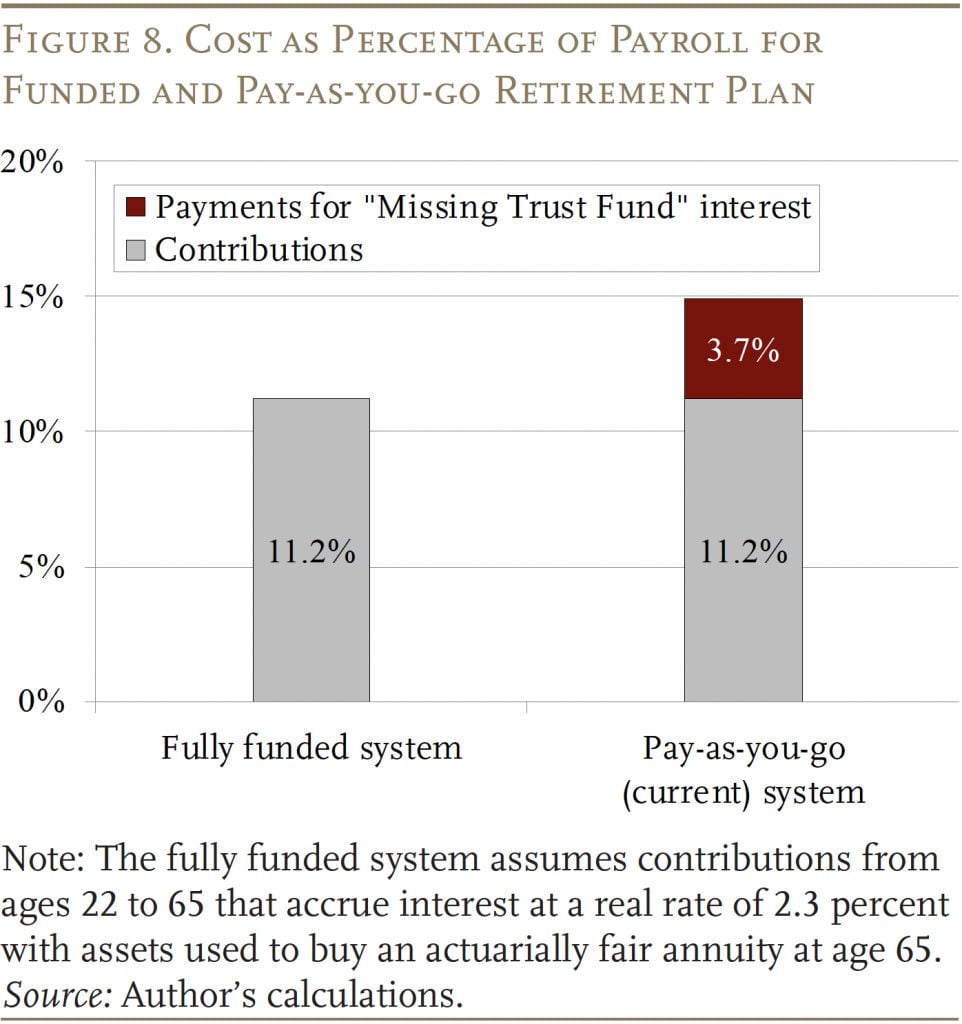

The simplest way to see the implications of Social Security’s Missing Trust Fund is to consider the contribution rate required to finance the program’s retirement benefits under a funded retirement plan compared to a pay-as-you-go system. This exercise uses the Social Security Trustees’ intermediate assumptions on mortality and on the real interest rate (2.3 percent) to achieve a replacement rate of about 36 percent (the Social Security replacement rate at 65 for the average earner). Under a funded system, the combined employer-employee contribution rate for a typical worker would be 11.2 percent of earnings. Under our pay-as-you-go system, the total cost is 14.9 percent, the sum of the current OASI tax rate of 10.6 percent and the deficit in the 75th year of the projection period of 4.3 percent. The resulting difference in cost to the worker between the funded and the pay-as-you-go system is 3.7 percentage points (14.9 percent minus 11.2 percent) (see Figure 8). This difference is due to the presence of a trust fund that can pay interest in a fully funded system but is missing in the pay-as-you-go system.

Interestingly, if Social Security were a fully funded program, the cost of the retirement benefits calculated above – 11.2 percent – would be very close to the current actual tax rate – 10.6 percent – for the retirement portion of Social Security. That is, most of the shortfall can be attributed to the fact that the program does not have a trust fund producing interest.

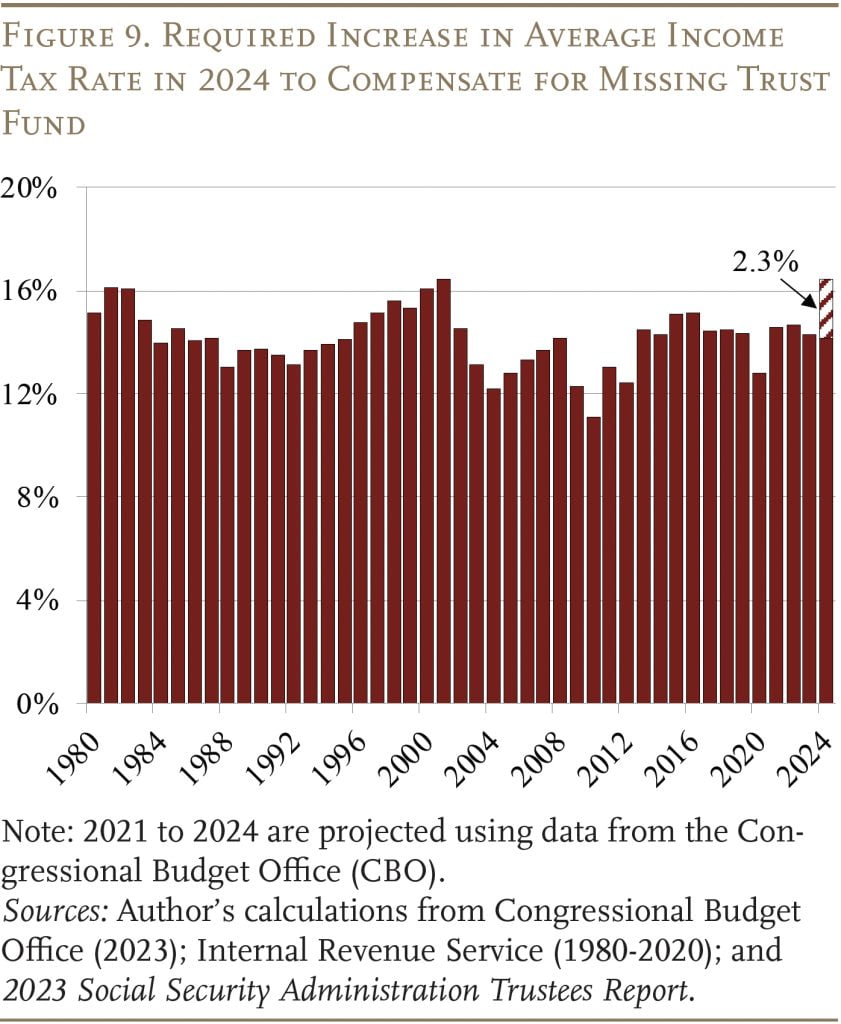

The question is whether workers should be asked to pay the higher payroll tax resulting from the decision to give away the trust fund or whether they should pay simply what they would have to contribute in a funded system. One could argue that the legacy burden should be borne by the general population in proportion to the ability to pay – that is, this part of the Social Security financing problem could be transferred to general revenues. If so, the average income tax rate (income taxes/adjusted gross income) would have to increase by 2.3 percentage points (from 14.1 percent to 16.4 percent) in 2024.2The required increase in the income tax rate in 2024 is calculated using projected taxable payroll from the Social Security Trustees’ Report and projected adjusted gross income (AGI) from the Congressional Budget Office. The calculation takes 3.7 percent of the projected taxable payroll (the difference in cost between a funded and pay-as-you-go system) to get a dollar amount and then divides it by projected AGI in 2024. The result, 2.3 percent, is the increase in the average income tax rate required to match a 3.7-percentage-point increase in the payroll tax. Even if we were to go all the way and raise taxes by enough to cover all Missing Trust Fund earnings, the average tax rate would still be within the bounds of historical experience (see Figure 9).

Conclusion

The 2023 Trustees Report confirms what has been evident for almost three decades – namely, Social Security is facing a long-term financing shortfall that equals 1 percent of GDP. The changes required to fix the system are well within the bounds of fluctuations in spending on other programs in the past. Moreover, action needs to be taken before the OASI trust fund is depleted in 2033 to avoid a precipitous cut in benefits. Americans support this program; their representatives should fix its finances.

This action-forcing event is a good time to rethink the financing of the system. An earmarked tax, however, is essential to the political stability of Social Security, which means that it is important to identify what should and what should not be paid for by this regressive levy. One could argue that the cost of giving away the trust fund associated with the start-up of the program should be borne by society in general in line with a broad measure of ability to pay. Thus, a strong rationale exists for shifting a portion of Social Security financing to general revenues. This is not a free lunch – income tax rates would have to increase. But this shift would represent a more equitable sharing of the burden. At the same time, workers would be paying an amount for their benefits equal to what they would have paid had a trust fund accumulated. Thus, the burden would be distributed more broadly, but the sense that workers pay for and are entitled to their benefits would remain.

References

Burkhalter, Kyle and Chris Chaplain. 2023. “Replacement Rates for Hypothetical Retired Workers.” Actuarial Note Number 2023.9. Baltimore, MD: U.S. Social Security Administration.

Chu, Sharon and Kyle Burkhalter. 2023. “Disaggregation of Changes in the Long-Range Actuarial Balance for the Old Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) Program Since 1983.” Actuarial Note Number 2023.8. Baltimore, MD: U.S. Social Security Administration.

Clingman, Michael, Kyle Burkhalter, and Chris Chaplain. 2014-2022. “Replacement Rates for Hypothetical Retired Workers.” Actuarial Note Number 9. Baltimore, MD: U.S. Social Security Administration.

Congressional Budget Office. 2023. “Long Term Budget Projections.” Washington, DC.

Internal Revenue Service. 1980-2020. “Statistics on Income Tax Stats – Individual Income Tax Return (1040).” Washington, DC.

Munnell, Alicia H., Wenliang Hou, and Geoffrey Sanzenbacher. 2019. “The Implications of Social Security’s ‘Missing Trust Fund.’” Issue in Brief 19-9. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

U.S. Social Security Administration. 1983-2023. The Annual Reports of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Endnotes

- 1Some commentators cite Social Security’s shortfall over the next 75 years in terms of dollars – $22.4 trillion. Although this number appears very large, the economy will also be growing. So, dividing this number – plus a one-year reserve – by taxable payroll over the next 75 years brings us back to the 3.61 percent-of-payroll deficit discussed above.

- 2The required increase in the income tax rate in 2024 is calculated using projected taxable payroll from the Social Security Trustees’ Report and projected adjusted gross income (AGI) from the Congressional Budget Office. The calculation takes 3.7 percent of the projected taxable payroll (the difference in cost between a funded and pay-as-you-go system) to get a dollar amount and then divides it by projected AGI in 2024. The result, 2.3 percent, is the increase in the average income tax rate required to match a 3.7-percentage-point increase in the payroll tax.