Canada Pension Plan Falls Short of Indexed Benchmark

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Canadian experience highlights the challenge of beating low-fee passive investments.

I’m a great fan of the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) and often cite it as a wonderful example of how to add equities to trust fund investments. Yet, the CPP’s most recent annual investments report shows that the returns from even this much-lauded effort have fallen short of the plan’s main “Reference Portfolio” – an 85%/15% mix of global public equities and Canadian government bonds. The fact that even the CPP cannot beat indexed investing buttresses the case that U.S. state and local pension plans should reassess their commitment to active management and alternative investments.

A little background. The CPP was initially set up in 1966 as a pay-as-you-go plan with a modest reserve, similar to the U.S. Social Security program. However, within a few decades, lower birth rates, longer life expectancies, and lower real wage growth led to increasing plan costs. To improve fairness across generations and ensure the long-term financial sustainability of the plan, Canada enacted legislation in 1997 that increased payroll contributions to its projected long-term rate and began investing some of the fund accumulations in equities.

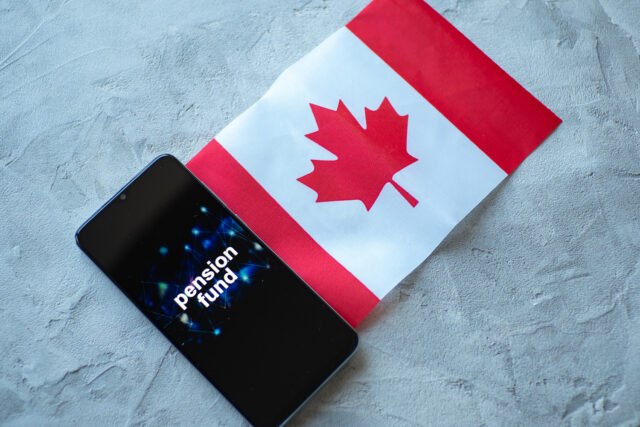

To implement the investment strategy, the legislation created the CPP Investment Board. The Board’s mandate is to invest CPP revenues not needed to pay current benefits to achieve the maximum return, without incurring undo risk, for the sole benefit of CPP contributors and beneficiaries. Initially, Canada followed a simple equity/bond strategy, but, in 2006, decided to shift to complex investments and active management. Since then, the CPP Investment Board has built a broad-based portfolio that includes not just stocks and bonds, but also real estate, infrastructure projects, and private equity (see Figure 1).

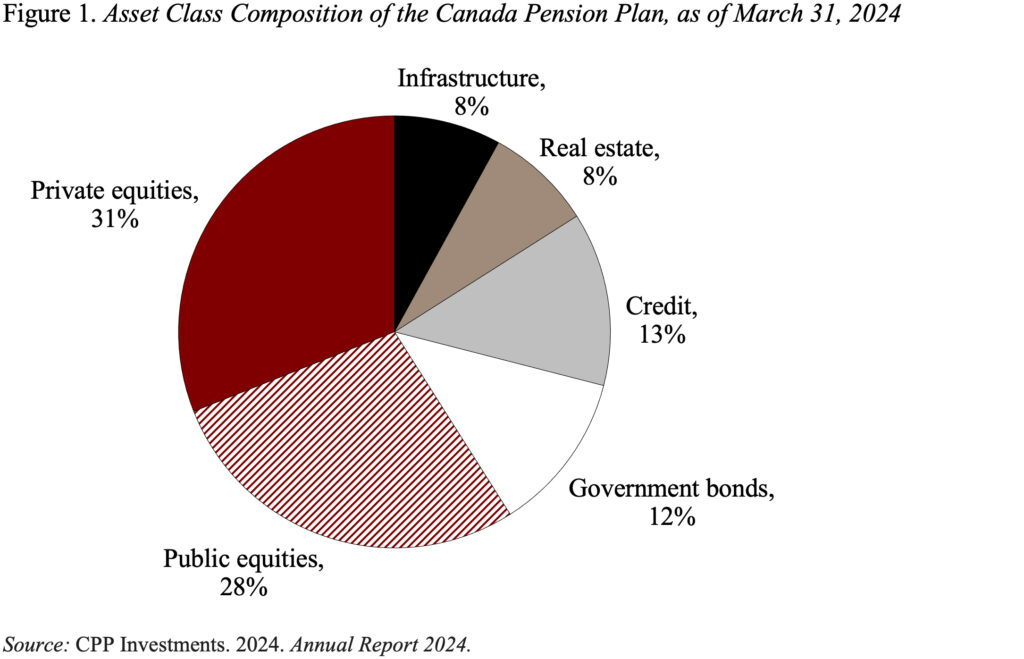

While the CPP Investment Board has one fund, it has six departments that invest and manage the assets. The managers are in-house, highly compensated individuals, and the global staff has grown from 100 in 2006 to 2,125 in 2024. The fund earned 8 percent on its investments in 2024 and has had annualized net returns of 9.2 percent over the last 10 years (see Figure 2).

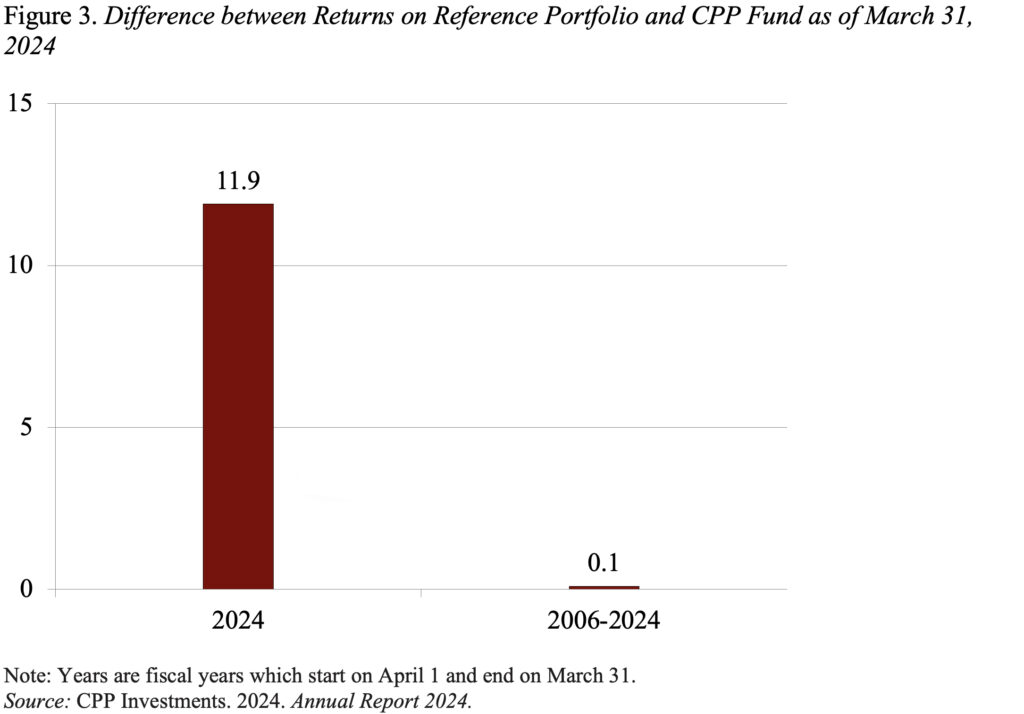

While the returns look impressive, they have fallen short of the Board’s 85/15 main Reference Portfolio. The difference was particularly stark in 2024, as U.S. equities, which account for half the equity holdings in the Reference Portfolio, soared (see Figure 3). As a result of these extraordinary gains, over the entire period 2006-2024 the Reference Portfolio edged out the Fund by 0.1 percent. That is, by not investing in an 85/15 mix of indexed stocks and bonds, the fund forfeited 42.7 billion CAD since the inception of active management in 2006. To be fair, of course, the results are very sensitive to the end year selected.

The purpose here is not to criticize the performance of the CPP Investment Board. It follows strict fiduciary standards, uses its influence in the private sector only to enhance long-run returns, and the President’s letter in the 2024 Report pushed back on pressure from Alberta to increase investments in Canada. The Board seems to do everything right, and has consistently been ranked as one of the top performing pension funds in the world over a 10-year period. The problem is that it can be very difficult to beat a low-fee indexed portfolio. The Canadian experience should be a cautionary tale for all investors and particularly those managing defined benefit plans.