Congressional Republicans Want Big Cuts to Social Security

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Proposals would rip away support for middle class.

The Republican Study Committee (RSC) has just released its FY 2024 Budget Protecting America’s Economic Security and once again called for significant cuts to Social Security. The RSC has served as the conservative caucus of House Republicans since its founding in 1973, and it currently consists of 175 of the 222 Republican House members. The group has been proposing cuts for decades, but the current round puts them at odds with the GOP presidential frontrunners. Donald Trump has urged Republicans not to cut a single penny from Social Security and Medicare; similarly, Ron DeSantis has said that he is “not going to mess with Social Security.”

The proposal in the RSC document is titled Preventing Biden’s Cuts to Social Security. If you haven’t heard of any cuts proposed by President Biden, that’s because he hasn’t made any. The provocative title refers to the cuts that would occur in the early 2030s when the reserves in the trust fund are exhausted. By law, Social Security cannot provide benefits for which it does not have financing and – once the trust fund is exhausted – incoming payroll taxes and other revenues would be sufficient to pay only 77 percent of scheduled retirement benefits. Hence, current and future beneficiaries would see an across-the-board cut of 23 percent in 2033.

The exhaustion of the trust fund is indeed an action-forcing event. No one wants to see benefits suddenly cut by 23 percent. The options are straightforward. Social Security is a simple system – money in/money out. Either more money must go in or less money must go out.

On the money-in side, the RSC points out that Biden’s prohibition against raising taxes on those earning under $400,000 precludes increasing the payroll tax rate. I hope that is not a binding constraint; a small increase in the payroll tax rate should probably be part of any solution. The RSC also rules out general revenues by framing such a contribution as coming from borrowing. Indeed, an economically sound approach would require raising income taxes to generate the required general revenues. And a strong rationale exists for a general revenue contribution – namely the cost associated with having given away the trust find to early groups of retirees. Specifically, today’s workers have to contribute much more to Social Security than they would to a funded retirement program.

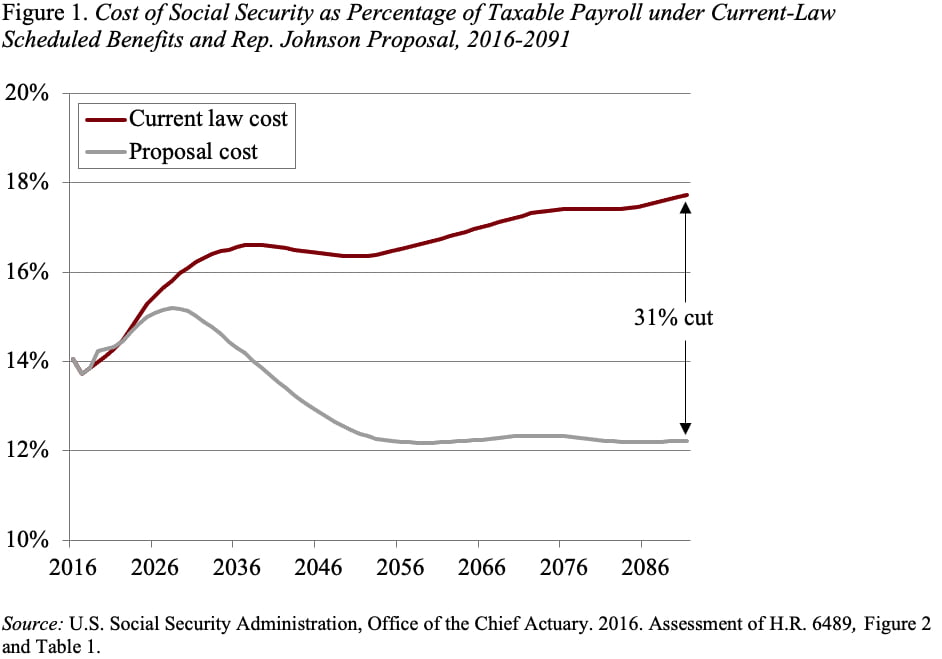

With revenues off the table, the RSC proposes to eliminate Social Security’s 75-year deficit solely by cutting benefits. To the extent the that the current package, like last year’s, is modelled on a bill put forward in 2016 by Sam Johnson (R-TX), it’s worth taking a closer look at that bill. According to scoring by the Social Security actuaries at the time, the Johnson plan would reduce Social Security costs at the end of the 75-year projection period by 31 percent (see Figure 1).

This 31-percent cut is the result of three major changes:

- raising the Full Retirement Age – currently 67 – to 69;

- dramatically reducing benefits for above-average earners; and

- eliminating the cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) for those with higher incomes and using a chain-weighted inflation index for those who qualify for a COLA.

At first glance, one might conclude that’s a fine outcome – cut the benefits of the well paid and preserve the benefits of the low paid. But the medium worker, who sees benefits drop to 77 percent of current law, had career average earnings of $58,700 in 2022 and the “high” earner, who sees benefits drop to 40 percent of current law, earned $94,000. These are not rich people.

Moreover, changes to Social Security need to be made in the context of the entire retirement income system. Many households are likely to retire with little other than Social Security benefits, since at any moment in time less than half the private sector workforce participates in an employer-sponsored retirement plan. Policymakers do need to address Social Security’s long-run deficit, but the fact that a majority of House Republicans may support a plan that cuts Social Security by a third should terrify voters. Why put out such a document?