Could Social Security Child Benefits Help Grandparent Caregivers?

The brief’s key findings are:

- Grandparents raising grandchildren are often under financial stress but – without legal custody – tend to get little formal support.

- Importantly, Social Security child benefits are only available to those who are legal dependents of Social Security beneficiaries.

- In contrast, the IRS does not require legal custody to claim a child as a dependent for tax purposes.

- The analysis estimates the impact of aligning Social Security’s rules with the IRS criteria on grandparent caregivers.

- The results show that this change would substantially boost the incomes of half of all grandparent caregiver households.

Introduction

Around two million grandparents are responsible for the basic needs of their grandchildren, with such caregiving concentrated in historically disadvantaged communities. While these grandparent caregivers are often under great financial pressure, they are generally ineligible for formal support because they raise their grandchildren outside of the foster care system without taking legal custody. As a result, they often do not receive the subsidies provided for foster parents, housing assistance, or Social Security child benefits.

This brief, based on a recent paper, explores the economic status of grandparent caregivers by focusing on two questions: 1) To what extent do grandparent caregivers differ from more typical grandparents in terms of economic resources? and 2) How would their finances improve if they were eligible for Social Security child benefits?1Liu and Quinby (2023).

The discussion proceeds as follows. The first section provides background on the sources of support currently available to grandparent caregivers. The second section describes the data and methodology for the analysis. The third section presents the results. The final section concludes that expanding eligibility for Social Security child benefits could be an important tool to improve the well-being of grandparent caregivers who have already claimed their own benefits.

Background

Grandparents often become caregivers to grandchildren after an adult child is no longer available due to death, incarceration, or substance abuse.2Hadfield (2014). The demands of raising grandchildren can drain savings, while time-consuming caregiving responsibilities create barriers to working longer and may force grandparents to retire early. Unsurprisingly, given these circumstances, grandparent caregivers are particularly vulnerable financially.3Fuller-Thomson, Minkler, and Driver (1997) and Baker, Silverstein, and Putney (2008). Grandparent caregivers are also more likely to experience both physical and mental health issues compared to non-caregivers of similar ages (Hadfield 2014).

Most grandparent caregivers receive little formal support because they do not legally adopt their grandchildren. Without legal custody, they are typically not eligible for state benefits, such as subsidies for foster parents, housing assistance, and counseling.4Radel et al. (2016) and U.S. Government Accountability Office (2020). Grandparents with low incomes can apply for child-only benefits provided by the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. However, doing so requires grandparents to assign to the state their rights to child support payments from non-custodial parents.5Fewer than one-tenth of grandparent caregivers actually claim TANF benefits, possibly due to both the reluctance to transfer the rights to child support and lagging TANF benefit levels (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2022 and Thompson, Azevedo-McCaffrey, and Carr 2023).

Another source of government support – Social Security child benefits – is available only to legal dependents of Social Security beneficiaries.6Additionally, children with disabilities are eligible for Supplemental Security Income (SSI). However, in 2004, only 0.6 percent of children in the care of grandparents received SSI (Murray, Macomber, and Geen 2004). Thus, children can receive benefits as a dependent of a grandparent beneficiary if: 1) they are not already receiving survivor or child benefits through a parent; 2) the grandparent formally adopts them; and 3) the grandparent provides at least half of their support. However, very few grandparent caregiver households claim Social Security child benefits, possibly due to the adoption requirement.7In 2002 – the most recent estimate – the share of grandchildren in the care of grandparent caregivers receiving support from Social Security child benefits was only 2 percent (Murray, Macomber, and Geen 2004).

The only federal support for grandparents who do not adopt their grandchildren comes from personal income tax preferences for dependents. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) permits grandparents who file taxes to claim their grandchildren as dependents if the children live in the household for at least half the year and the grandparents provide at least half their support, so legal custody is not required.8Revenue Procedure 2015-53.

The general lack of support for grandparent caregivers combined with the tremendous financial strain of child-rearing has sparked policy interest in helping this group.9The Supporting Grandparents Raising Grandchildren Act of 2018 created a Federal Advisory Council with participation from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of Education. The Council is currently developing a National Family Caregiving Strategy to identify policies to increase the financial security of family caregivers, including grandparents (Advisory Council to Support Grandparents Raising Grandchildren 2021). Hence, the goal of this study is to assess how Social Security child benefits could improve the financial well-being of grandparent caregivers if the guardianship requirement were loosened to be on par with the IRS criteria for claiming a dependent grandchild.

Data and Methodology

This study uses the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) linked with the U.S. Social Security Administration’s earnings data and Master Beneficiary Record (MBR) to identify grandparent caregivers, assess their financial well-being, and calculate potential Social Security child benefits under relaxed eligibility requirements. The HRS contains rich information on caregiving, household finances, and Social Security benefits for households over age 50.

The analysis proceeds in two stages. The first stage identifies grandparent caregivers in the HRS and compares their financial well-being to more typical grandparents. Specifically, we define caregivers as those who report “raising” a grandchild residing in the household and identify 1,465 such households in the HRS sample between 2002 and 2020.10Information on raising grandchildren is limited and inconsistent in the HRS prior to 2002. While this definition is not precisely aligned with the IRS criteria for claiming a dependent grandchild, the share of older households caregiving in the HRS closely tracks results using the IRS criteria in other datasets. See Liu and Quinby (2023) for more details. Our sample of non-caregivers contains 14,575 grandparent households. We evaluate financial well-being by comparing the financial wealth, retirement plan wealth, and Social Security wealth of grandparent caregivers to non-caregivers.11Financial wealth includes assets in checking and other financial accounts minus non-mortgage debt. Retirement plan wealth measures the total balance in employer defined contribution retirement plans and IRAs plus the expected present value of defined benefit plans. Social Security wealth calculates the expected present value of retirement, spousal, and survivor benefits based on the respondent’s and spouse’s earnings record. For more detail on our wealth calculations, see Chen, Munnell, and Quinby (2023). We exclude housing wealth because most older households do not tap their home equity for everyday expenses (Venti and Wise 2004, Munnell et al. 2020). Throughout, we focus on historically disadvantaged groups, because older Black and Hispanic households are more likely to end up caring for their grandchildren.

The second stage of the analysis examines how expanding access to Social Security child benefits would improve the well-being of grandparent caregivers. We start by examining the share of caregiver households that would be eligible for child benefits under looser eligibility criteria. Then, we estimate the amount of child benefits that newly eligible households would receive under expanded access, using linked administrative data on claiming and benefit amounts.12The final sample includes 454 caregiver households that have linked MBR data and have started claiming Social Security OASDI benefits when last observed raising a grandchild with similar demographic characteristics, economic resources, and caregiving patterns as the full sample. The child benefits would equal 50 percent of the highest-earning grandparent’s Primary Insurance Amount, capped at a family maximum. Lastly, we estimate how the household’s replacement rate – retirement income relative to pre-retirement earnings – changes should the household gain access to child benefits.13The numerator of the replacement rate, retirement income, equals Social Security income (with or without child benefits) in the SSA administrative beneficiary records plus annuitized financial and retirement wealth. The denominator, pre-retirement earnings, is defined as the average of the highest five years of earnings after age 45 in the SSA administrative earnings file.

Results

This discussion begins with an overview of the characteristics of the grandparent caregiver population. It then turns to how expanded eligibility for Social Security child benefits could help.

Who Are the Grandparent Caregivers?

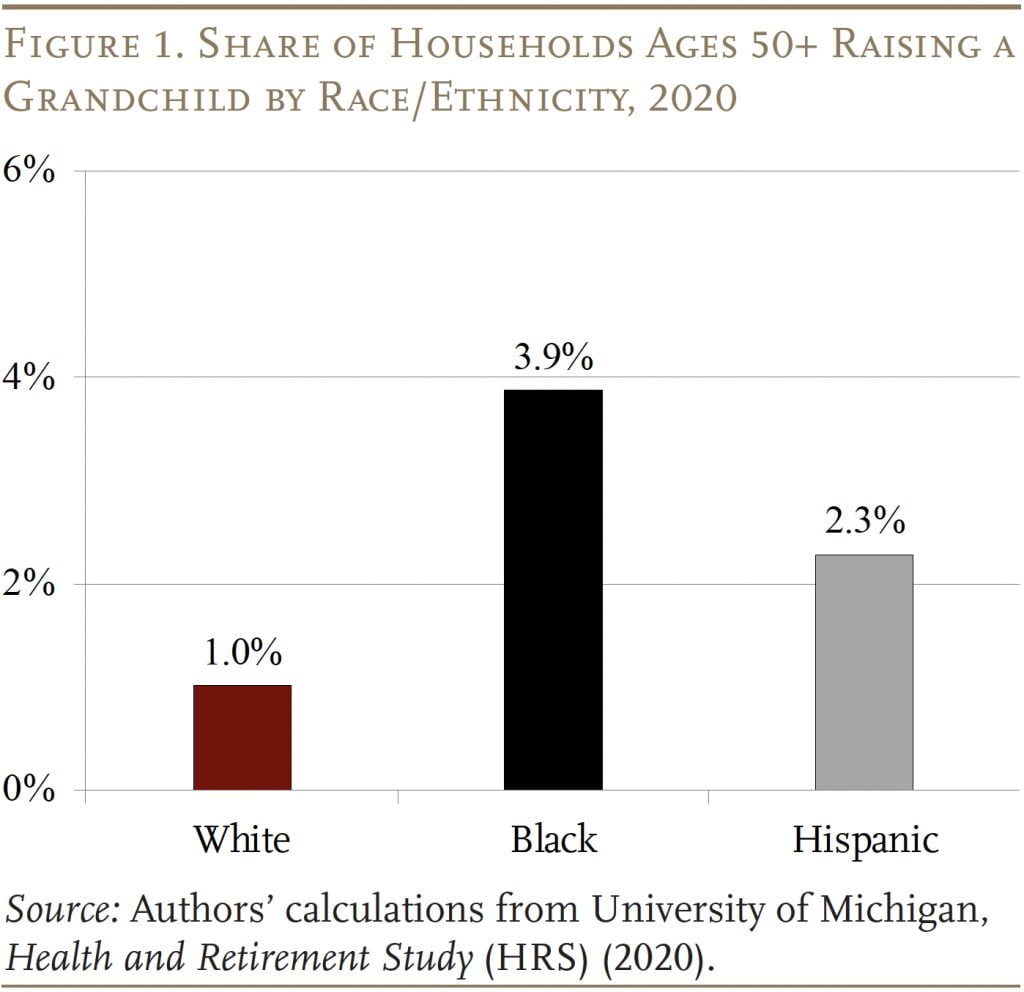

Consistent with prior literature, we find that grandparents of color, particularly Black grandparents, are more likely to become caregivers. In 2020, only around 1 percent of White households over age 50 reported raising a grandchild, compared to 4 percent of Black and 2 percent of Hispanic households, respectively (see Figure 1). Compared to typical grandparents, caregivers are also less likely to have a college degree and more likely to be single women.

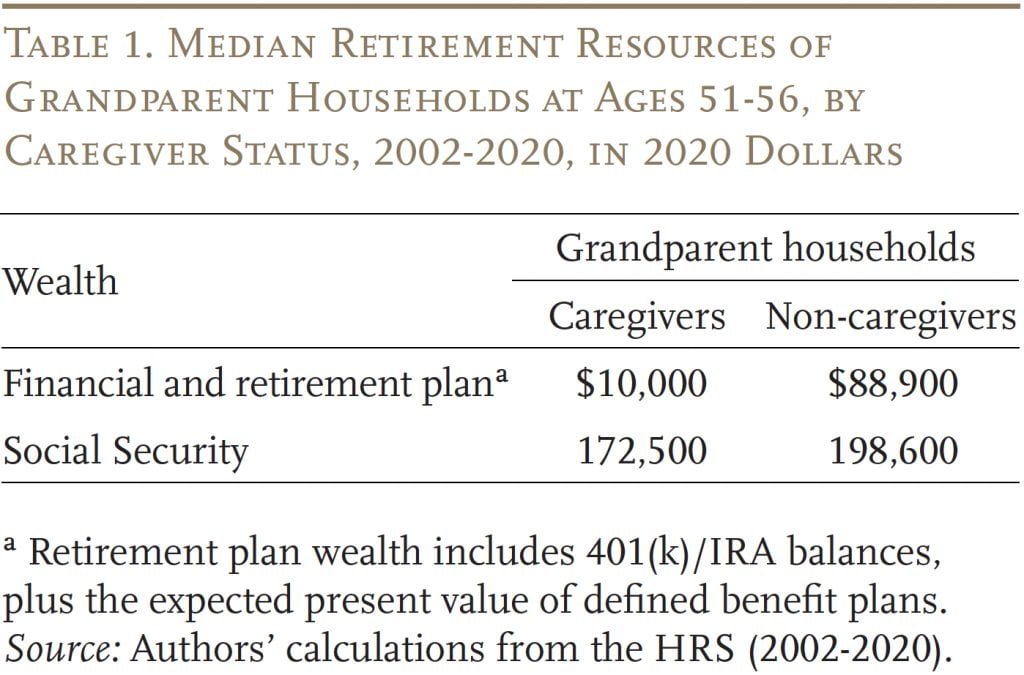

Not surprisingly, grandparent caregivers have significantly fewer economic resources prior to retirement compared to non-caregivers. Whereas the median non-caregiver household has $89,000 in financial and retirement accounts, the median caregiver has just $10,000 (see Table 1). Fortunately, Social Security is a great equalizer, providing nearly as much in retirement wealth for caregivers as for non-caregivers.14Of course, demographic and economic disparities by caregiver status are hardly surprising due to the overrepresentation of non-White groups among caregivers. However, even comparing caregivers and non-caregivers of the same race/ethnicity, caregivers remain economically disadvantaged.

How Much Can Expanding Access to Child Benefits Help?

We next turn to our thought experiment: how aligning the eligibility criteria for Social Security child benefits with the IRS criteria for claiming a dependent grandchild would improve the household’s financial well-being. Even under the more lenient IRS criteria, caregiver households would still only be eligible for child benefits once the grandparents have themselves claimed retirement or disability benefits. So, the first step is to determine the timing and duration of caregiving to see how it aligns with benefit receipt.

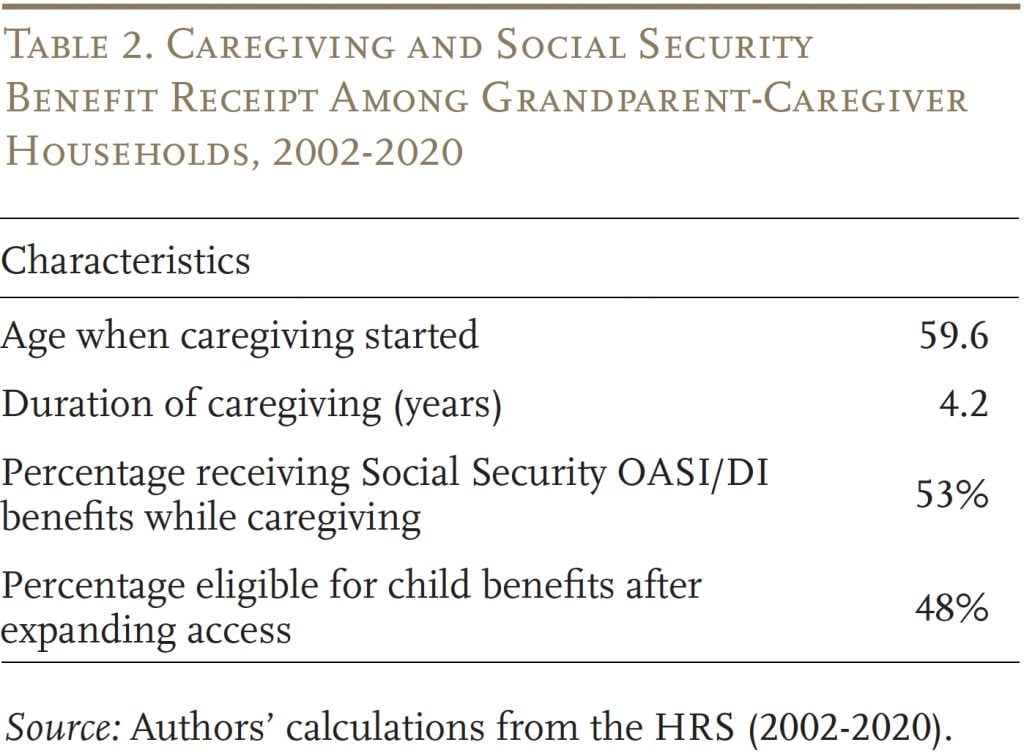

A typical grandparent caregiver raises their grandchildren for four years, beginning around age 60 (see Table 2). Although many of these grandparents are still relatively young, more than 50 percent receive Social Security benefits while caring for their grandchildren – either because they claim retirement benefits early or are receiving disability benefits.15The median claiming age for grandparent caregivers is 62 and nearly a quarter receive Disability Insurance. Since few beneficiary households have grandchildren who are already receiving Social Security benefits through a parent, close to half of grandparent caregiver households would qualify for child benefits if the eligibility criteria were aligned with the IRS rules.16We use imputations based on self-reported information on non-job income from other household members. See Liu and Quinby (2023) for more details. The share of eligible households is even higher among Black and Hispanic caregivers.

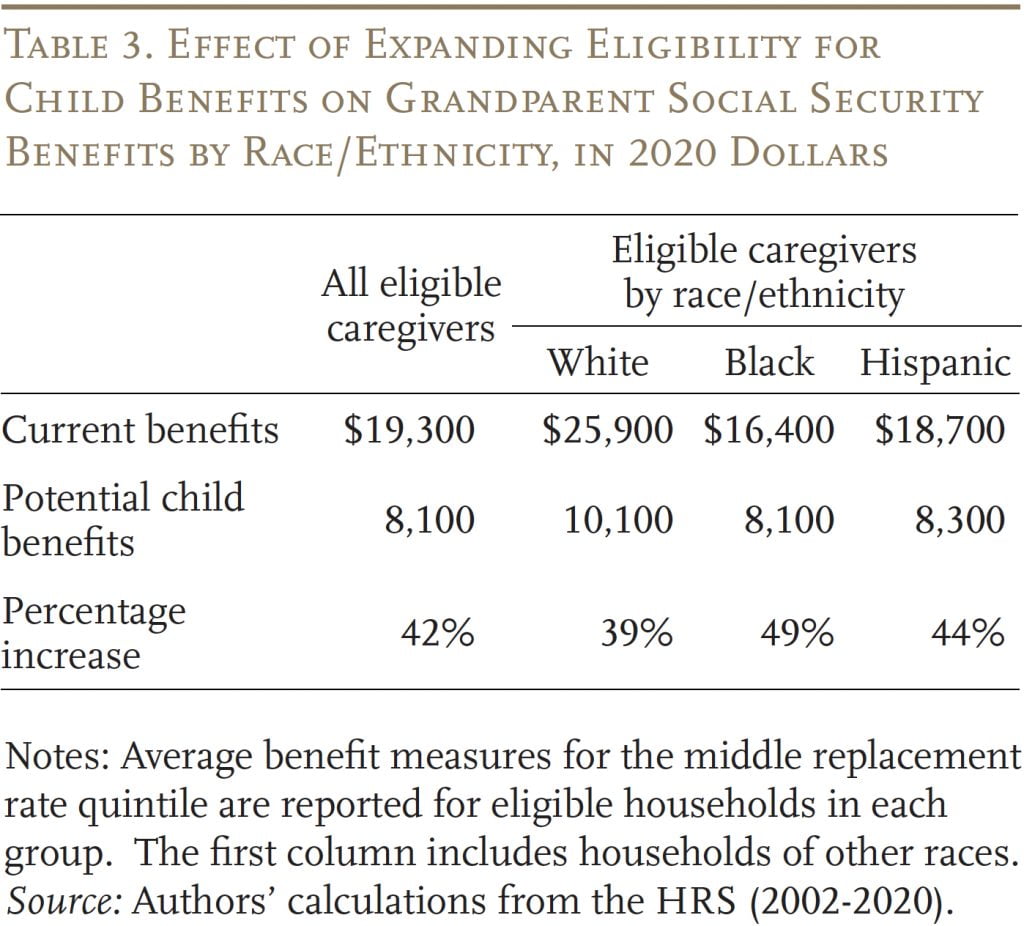

The next step is to determine how much grandparent caregivers would get if their household were eligible for child benefits under the more expansive eligibility criteria. The amounts turn out to be substantial – the typical eligible household would receive $8,100 in child benefits on top of their current annual benefits of $19,300 (see Table 3). While Black and Hispanic caregivers would receive lower dollar amounts than White caregivers, both groups would enjoy a higher percentage increase in annual benefits.17Although child benefits are calculated as 50 percent of the highest-earning grandparent’s Primary Insurance Amount, households can receive more than a 50-percent increase overall if they care for multiple grandchildren, or if the highest-earning grandparent is no longer present in the household.

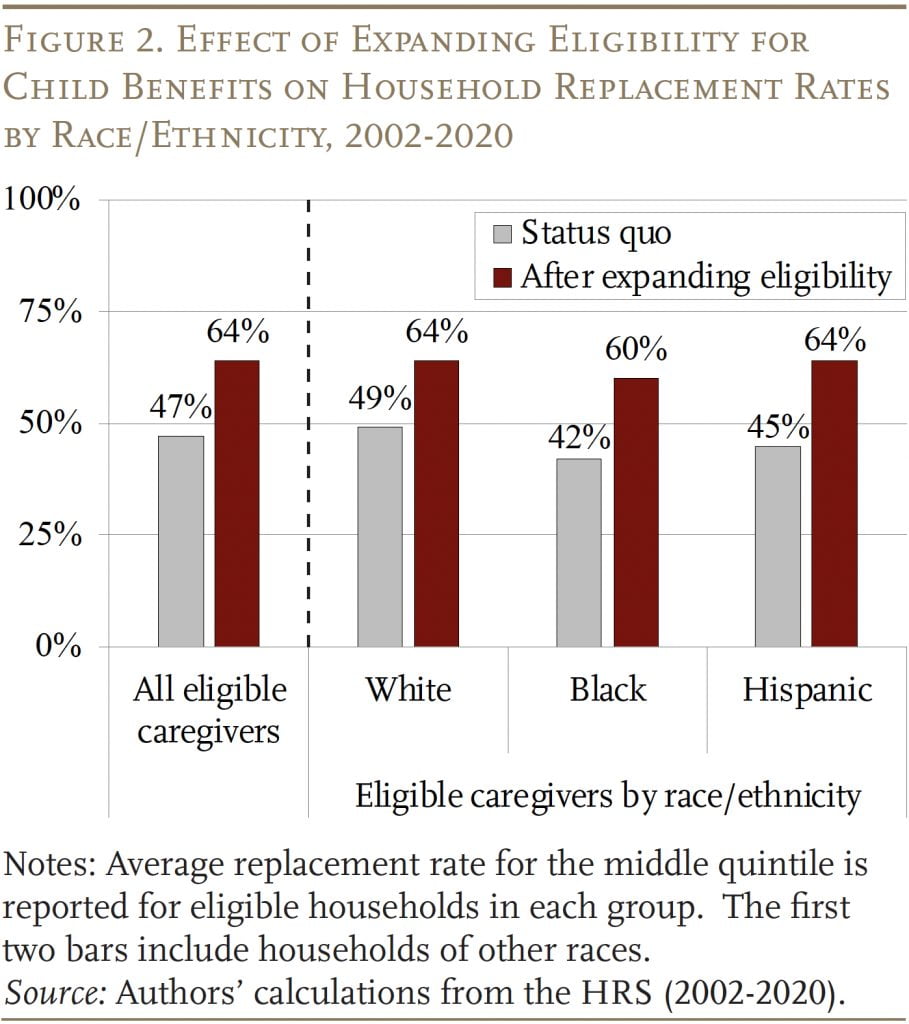

The additional income from expanded child benefits would notably improve households’ replacement rates (see Figure 2). The typical caregiver’s replacement rate would rise from 47 percent to 64 percent. Again, Black and Hispanic households would see greater improvements than White households, as they would experience increases of 18 and 19 percentage points, respectively.

Conclusion

Grandparents who raise grandchildren are disproportionately Black and Hispanic, and have almost no personal savings. Despite being more vulnerable to financial insecurity, most of these caregivers receive little formal support because they do not have legal custody of the grandchildren in their care.

To reduce the financial strain of grandparent caregiving, Social Security child benefits could be a valuable tool. The most obvious approach would be to substitute the current IRS requirements for the SSA’s current requirement of adoption. Around half of caregiver households would benefit from expanded access to these benefits, and replacement rates for those affected are estimated to increase by 17 percentage points, on average. Notably, Black and Hispanic households would enjoy a substantial increase in income.

An important caveat is that a meaningful share of grandparent caregivers would still not be helped by such a policy change because they have not yet retired and claimed their own Social Security benefits. Consequently, Social Security child benefits can best be viewed as a complement to other existing forms of support.

References

Advisory Council to Support Grandparents Raising Grandchildren. 2021. “Supporting Grandparents Raising Grandchildren (SGRG) Act, Initial Report to Congress.” Washington, DC.

Baker, Lindsey A., M. Silverstein, and N. M. Putney. 2008. “Grandparents Raising Grandchildren in the United States: Changing Family Forms, Stagnant Social Policies.” Journal of Social Policy 7: 53-69.

Chen, Anqi, Alicia H. Munnell, and Laura D. Quinby. 2023. “Why Do Late Boomers Have So Little Wealth and How Will Early Gen-Xers Fare?” Working Paper 2023-6. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Fuller-Thomson, Esme, Meredith Minkler, and Diane Driver. 1997. “A Profile of Grandparents Raising Grandchildren in the United States.” The Gerontologist 37(3): 406-411.

Hadfield, J. C. 2014. “The Health of Grandparents Raising Grandchildren: A Literature Review.” Journal of Gerontological Nursing 40: 32-42.

Internal Revenue Service. 2015. “Revenue Procedure 2015-53.” Washington, DC.

Liu, Siyan and Laura D. Quinby. 2023. “How Can Social Security Children’s Benefits Help Grandparents Raise Grandchildren?” Working Paper 2023-9. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Munnell, Alicia H., Abigail N. Walters, Anek Belbase, and Wenliang Hou. 2020. “Are Homeownership Patterns Stable Enough to Tap Home Equity?” The Journal of the Economics of Ageing 17: 100277.

Murray, Julie, Jennifer Ehrle Macomber, and Rob Geen. 2004. “Estimating Financial Support for Kinship Caregivers.” Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Radel, Laura, Matthew Bramlett, Kirby Chow, and Annette Waters. 2016. “Children Living Apart from Their Parents: Highlights from the National Survey of Children in Nonparental Care.” Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

Thompson Gina A., Diana Azevedo-McCaffrey, and Da’Shon Carr. 2023. “Increases in TANF Cash Benefit Levels Are Critical to Help Families Meet Rising Costs.” Policy Brief. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

University of Michigan. Health and Retirement Study, 2022. Respondent Cross-Year Benefits Restricted Dataset. Produced and distributed by the University of Michigan with funding from the National Institute on Aging (Grant Number NIA U01AG009740). Ann Arbor, MI.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2022. “Characteristics and Financial Circumstances of TANF Recipients Fiscal Year (FY) 2019.” Washington, DC.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. 2020. “HHS Could Enhance Support for Grandparents and Other Relative Caregivers.” Washington, DC.

Venti, Steven F. and David A. Wise. 2004. “Aging and Housing Equity: Another Look.” In Perspectives on the Economics of Aging, edited by David A. Wise, 127-180. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Endnotes

- 1Liu and Quinby (2023).

- 2Hadfield (2014).

- 3Fuller-Thomson, Minkler, and Driver (1997) and Baker, Silverstein, and Putney (2008). Grandparent caregivers are also more likely to experience both physical and mental health issues compared to non-caregivers of similar ages (Hadfield 2014).

- 4Radel et al. (2016) and U.S. Government Accountability Office (2020).

- 5Fewer than one-tenth of grandparent caregivers actually claim TANF benefits, possibly due to both the reluctance to transfer the rights to child support and lagging TANF benefit levels (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2022 and Thompson, Azevedo-McCaffrey, and Carr 2023)

- 6Additionally, children with disabilities are eligible for Supplemental Security Income (SSI). However, in 2004, only 0.6 percent of children in the care of grandparents received SSI (Murray, Macomber, and Geen 2004).

- 7In 2002 – the most recent estimate – the share of grandchildren in the care of grandparent caregivers receiving support from Social Security child benefits was only 2 percent (Murray, Macomber, and Geen 2004).

- 8Revenue Procedure 2015-53.

- 9The Supporting Grandparents Raising Grandchildren Act of 2018 created a Federal Advisory Council with participation from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of Education. The Council is currently developing a National Family Caregiving Strategy to identify policies to increase the financial security of family caregivers, including grandparents (Advisory Council to Support Grandparents Raising Grandchildren 2021).

- 10Information on raising grandchildren is limited and inconsistent in the HRS prior to 2002. While this definition is not precisely aligned with the IRS criteria for claiming a dependent grandchild, the share of older households caregiving in the HRS closely tracks results using the IRS criteria in other datasets. See Liu and Quinby (2023) for more details.

- 11Financial wealth includes assets in checking and other financial accounts minus non-mortgage debt. Retirement plan wealth measures the total balance in employer defined contribution retirement plans and IRAs plus the expected present value of defined benefit plans. Social Security wealth calculates the expected present value of retirement, spousal, and survivor benefits based on the respondent’s and spouse’s earnings record. For more detail on our wealth calculations, see Chen, Munnell, and Quinby (2023). We exclude housing wealth because most older households do not tap their home equity for everyday expenses (Venti and Wise 2004, Munnell et al. 2020).

- 12The final sample includes 454 caregiver households that have linked MBR data and have started claiming Social Security OASDI benefits when last observed raising a grandchild with similar demographic characteristics, economic resources, and caregiving patterns as the full sample.

- 13The numerator of the replacement rate, retirement income, equals Social Security income (with or without child benefits) in the SSA administrative beneficiary records plus annuitized financial and retirement wealth. The denominator, pre-retirement earnings, is defined as the average of the highest five years of earnings after age 45 in the SSA administrative earnings file.

- 14Of course, demographic and economic disparities by caregiver status are hardly surprising due to the overrepresentation of non-White groups among caregivers. However, even comparing caregivers and non-caregivers of the same race/ethnicity, caregivers remain economically disadvantaged.

- 15The median claiming age for grandparent caregivers is 62 and nearly a quarter receive Disability Insurance.

- 16We use imputations based on self-reported information on non-job income from other household members. See Liu and Quinby (2023) for more details.

- 17Although child benefits are calculated as 50 percent of the highest-earning grandparent’s Primary Insurance Amount, households can receive more than a 50-percent increase overall if they care for multiple grandchildren, or if the highest-earning grandparent is no longer present in the household.