Cut Medicare? Ok, But How?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

In his address to Congress on September 8th, President Obama indicated his willingness to cut Medicare. Certainly Medicare is a major contributor to the deficit, and reducing Medicare costs would help the long-run fiscal outlook. The question is how to cut the program. The smart cuts can’t be done by politicians, but rather involve eliminating unnecessary medical spending. All the usual suspects have the potential to do more harm than good.

Raise age of eligibility from 65 to 67. Such an increase would bring Medicare eligibility in line with the Social Security full retirement age. It could also encourage people to delay retirement so they do not spend periods without health insurance. But basically, this is a cost shifting proposal. Medicare costs would go down, but individuals and (the dwindling number of) employers that offer retiree health insurance would have to pay more. States’ spending on Medicaid would also be higher.

Raise Part B premium to 35 percent of program costs. Medicare Part B allows beneficiaries to obtain coverage for physician services and other outpatient services by paying a monthly premium. The current standard Part B premium is $115.40. Raising the premium to 35 percent of program costs would increase the premium to $161.56. This increase would be a meaningful reduction in monthly income for most retirees. It would also raise costs for states that pay premiums for people eligible for coverage through both Medicare and Medicaid. It is just another form of cost shifting.

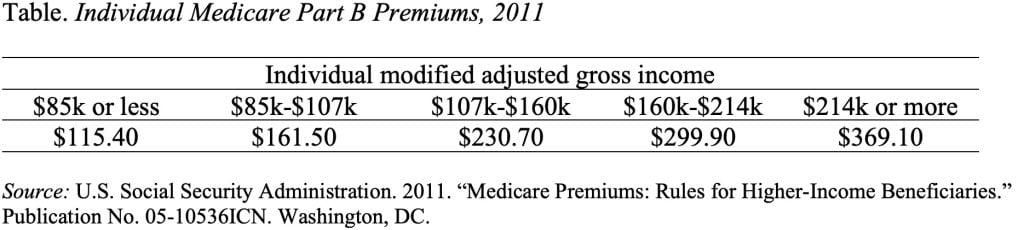

Means-test premiums. If the program is in trouble, why not make higher income people pay more? The answer here is that they already do. As the Table shows, Medicare Part B premiums for high income people are3.2 times the standard premium. Premiums for Medicare Part D, the prescription drug program, are also means-tested.

Raise co-payments and deductibles. Medicare Part A (primarily hospital and post-acute care) has a deductible of $1,132 for “each spell of illness” and enrollees are subject to substantial daily copayments for extended hospital and skilled nursing stays. Medicare Part B has an annual deductible of $162 and a co-payment of 20 percent for most services and a higher percent for others. Because the cost-sharing requirements are substantial, most participants obtain supplemental coverage through their employers, a Medigap policy, or Medicaid. Nevertheless, the risk with raising co-pays and deductibles is that people forego primary care visits and end up being hospitalized with more expensive problems.

Cut payments to providers. Such across-the-board cuts (which will kick in if the special congressional committee does not reach agreement) raise two issues. First, they do not distinguish between providers or between services. In high spending areas, all providers would face cuts, even those that did not contribute to the problem. Similarly, payments for all services, regardless of their value to the patient, would be cut. Second, they are very hard to enforce as evidenced by the fact that Congress has repeatedly overridden dollar caps on payments to physicians.

If the usual suspects aren’t the answer, then how do we get Medicare spending under control? Here, I am not the expert. One issue is the extent to which doctors practice defensive medicine because of fear of being sued. If frivolous lawsuits are a real problem, then tort reform would help.

The other area is treatments that are either not effective or more expensive than others that would produce equally good results. In a recent New York Times Op-ed “Cut Medicare, Help Patients,” Ezekiel J. Emanuel and Jeffrey B. Liebman cited a number of such ineffective or excessively expensive treatments that are currently covered by Medicare, including colonoscopies for people over 75 even though researchers find no evidence they save lives, Avastin for the treatment of breast cancer even though the Food and Drug Administration found it is not effective, and stents for heart patients without trying the less expense drug therapy first.

Eliminating such ineffective and inappropriate treatments is the best way to control Medicare spending and reduce the deficit. Congress cannot select medications and procedures; only doctors and hospitals can. They are more likely do it if payments are based on the quality of the care provided patients than on the number of procedures. None of the usual suspects for cutting Medicare are likely to improve the incentives to practice better medicine.