Why Women’s Money Behavior Should Be Studied Separately from Men

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

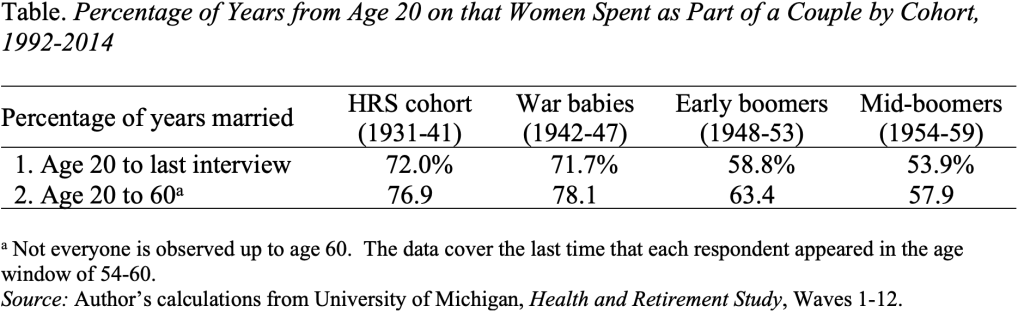

Women’s adult years spent as part of a couple declined sharply.

People are often interested in studying the saving behavior of women. I have generally resisted that approach because women have traditionally lived in households where the couple makes decisions jointly. In that world, I would think that married women and single women would look more different than men and women.

But the times are changing, so it makes sense to see if women are still spending most of their lives in households. To find out, we (actually our research associate Sara King) looked at the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), which has interviewed people ages 50 and older every two years since 1992. The question is what percentage of women’s years – between age 20 and the last time interviewed – are spent as part of a couple. The HRS asks detailed questions about both current and past marital status. In a few cases, the responses were crazily inconsistent, so these women were eliminated from the sample.

The results are shown in the first row of the table, and they are very interesting. For the earliest cohort, those born 1931-41, 72% of women’s years between age 20 and the last interview were spent married. By the mid-baby-boomer cohort, those born 1954-59, the share had dropped to 53.9%. That drop means that women have gone from spending most of their lives as part of a couple to spending almost half of their lives single.

One concern with the numbers in the first row of the table is that the ending age differs across cohorts. That is, the ages of mid-boomers in 2014, the date of the latest interview, were 55 to 60, while the ages for the HRS cohort in 2014 were 73 to 83. Therefore, it’s possible that the results in the first row could just be due to the age ranges and/or years spent as a widow.

Therefore, we calculated a second set of numbers based on a standard age, which appear in the second row of the table. Interestingly, the pattern persists. The percentage of years that women spent as part of a couple has indeed declined. It may be that, once the whole lifespan of mid-boomers has elapsed, women in that cohort will have spent less than half their adult years as part of a couple.

How did this dramatic change come about? First, the average age of first marriage rose by about 3 years between the HRS cohort and the mid-boomer cohort. Second, women spend more time divorced. And third, more women never marry.

The bottom line, however, is that if women as a group are going to spend about half of their adult years in a couple, it probably makes sense to separately explore their savings and investment behavior.