Don’t Trust the TRUST Act

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

We don’t need “Rescue Committees;” the Social Security 2100 Act could do the job.

Shivers went up my spine when I heard that the TRUST Act might be included as part of additional action on COVID-19. It sounds like a benign piece of bipartisan legislation, but it could well lead to major cuts to Social Security and Medicare.

The TRUST Act would create “Rescue Committees” for any federal government trust fund spending more than $20 billion annually that faces insolvency by 2035. Under these criteria, the TRUST Act would apply to Social Security’s Old Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) program, Medicare’s Hospital Insurance (HI) component, and the Highway Trust Fund. (Social Security’s separate Disability Insurance Trust Fund is scheduled to run out of money in 2065.)

Each Rescue Committee would consist of twelve current members of Congress, with three members chosen by the minority and majority leaders in the House and the Senate. The committee’s job would be to come up with legislative proposals to avoid trust fund depletion and assure the long-run solvency of each program. To be voted out by a Recue Committee, the package would require not only a majority but also at least two members of each party.

Once voted out, Congress would have to consider the package without amendment and within a specified time period. Both chambers and the President would have to approve the legislation for the package to become law. (Unlike in the case of the Defense Base Closing and Realignment Commission, the proposals would not go into effect simply if Congress failed to act.)

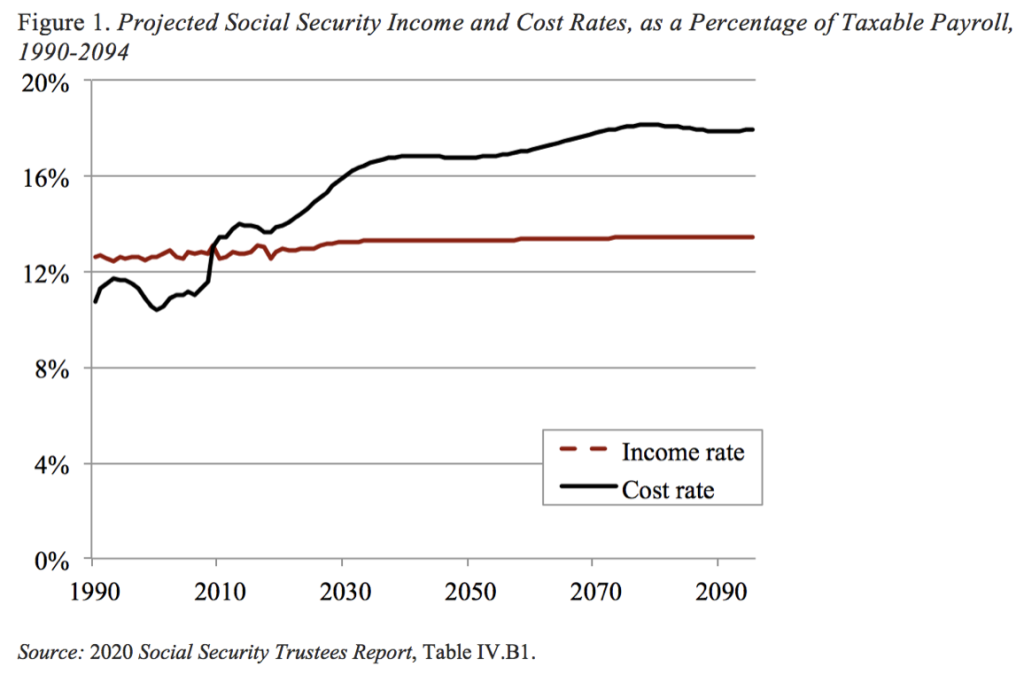

So, what’s so bad, you might ask. My main concern is Social Security. Indeed, it does have a trust fund that is running out of money and it does need to solve a long-run financing problem. Specifically, the cost of scheduled benefits exceeds scheduled revenues (see Figure 1), with the difference being bridged by the assets in the trust fund. These assets are projected to be depleted in 2034, and – if Congress takes no action – benefits will have to be cut by 20-25 percent.

Only two options exist for fixing Social Security – raise income or cut benefits. (No, increasing the retirement age is not a third option. It is simply a benefit cut.) And it’s so easy for negotiators to agree to a 50-50 approach – half benefit cuts and half revenue increases.

In my view, cutting benefits is unacceptable. People absolutely need at least the current level of benefits to have a fighting chance of security in retirement. The National Retirement Risk Index, which the Center produces, shows that – even with the current level of Social Security – more than half of today’s working-age households are at risk of being unable to maintain their standard of living in retirement.

That outcome is not surprising, given that today’s employer-sponsored 401(k) system results in meaningful asset accumulation only for the top one-fifth of the income distribution. The 401(k)/IRA holdings for those in the middle fifth are actually lower for the most recent cohort than for earlier ones. The result is that Social Security serves as the major or only source of income for millions of retirees. Benefits simply cannot be cut.

The financing problem, however, does need to be solved. Fortunately, that’s what the Social Security 2100 Act does. This proposed legislation slightly enhances benefits and substantially increases the income rate, thereby restoring 75-year solvency.

The legislation, which is co-sponsored by about 90 percent of House Democrats, increases benefits for all by shifting the price index to adjust for inflation and reduces taxation under the personal income tax, and helps the most vulnerable through an increase in the special minimum benefit and raising the first factor in the benefit formula from 90 to 93 percent.

To pay for these benefit enhancements and, more importantly to eliminate the 75-year deficit, the legislation: 1) raises the combined OASDI payroll tax of 12.4 percent by 0.1 percent per year until it reaches 14.8 percent in 2043; and 2) applies the payroll tax on earnings above $400,000 (and on all earnings once the taxable maximum reaches $400,000). The legislation includes a small offsetting benefit for these additional taxes.

With this legislation on the table, we don’t need “Rescue Committees.” Let’s have an open debate, then a vote, and see where we are.