Economic Insecurity for Older Adults in a High-Cost State

The brief’s key findings are:

- This study explores whether living in a high-wealth, high-cost state – like Massachusetts – helps or hurts retirees meet their basic needs.

- In Massachusetts, the cost of living outweighs higher incomes and wealth, so retirees are more likely to struggle than those in other states.

- Low-income retirees say they often need to adjust to a lower standard of living and that Social Security benefits and housing subsidies are key lifelines.

- State policymakers could help by: 1) improving property tax deferrals; and 2) adopting an auto-IRA to help workers save if they have no employer plan.

Introduction

Across the nation, many older adults struggle to make ends meet. The Elder Index, produced by the Gerontology Institute at UMass Boston, suggests that roughly one-third of older households have incomes below what it takes to meet basic needs and age in place. One question is whether living in a high-wealth, high-cost state such as Massachusetts makes things better or worse. On the one hand, Massachusetts’ salaries are higher than average and the state’s older households are more likely to be White and have a college degree, factors that are associated with greater financial stability. On the other hand, Massachusetts has an extraordinarily high cost of living and persistent economic inequality. Regardless of the state’s relative situation, the second question is how do older residents with low incomes cope.

This brief, which is based on a recent collaboration between Boston Indicators and the Center for Retirement Research, uses quantitative analysis to explore Massachusetts’ relative standing and a qualitative approach – interviews with older residents – to determine how those facing financial pressures make ends meet.1

The discussion proceeds as follows. The first section compares Massachusetts to the rest of the nation, using the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). The exercise shows that older households in Massachusetts are more likely to have inadequate income, as measured by the Elder Index, and that racial disparities are especially severe. The second section reports the findings from semi-structured interviews with older residents of greater Boston. Key findings are that many older adults must adjust to a lower standard of living in retirement; Social Security and subsidized housing are lifelines; and other government benefits also play an important role.

The final section concludes that two initiatives at the state level could make for a better future. First, high housing costs – including property taxes – are a major contributor to economic stress. Massachusetts, like many states, allows qualifying older adults to defer property tax payments for as long as they remain in their homes, but the program should be reformed to encourage participation and ensure financial sustainability. Second, retirees need more than Social Security, but many lack meaningful employer-based saving. Massachusetts could help close the savings gap by adopting the Secure Choice Savings Program – an automatic IRA for employees without access to an employer-sponsored retirement plan. These two changes would greatly improve the future financial well-being of Massachusetts’ older residents.

Financial Well-being of Older Households

Massachusetts is a high-income, high-wealth state, but it is also marked by high costs and persistent economic inequality. To assess the financial security of older adults in Massachusetts relative to the nation, the analysis proceeds in three stages. The first stage documents the financial resources available to older households in Massachusetts and compares those outcomes with other states. The second compares older households’ financial resources to the local cost of living to estimate the share of households unable to pay for their basic needs. The third replicates this analysis for different racial and ethnic groups.

Financial Resources: MA vs. Rest of U.S.

This analysis uses data from the 2019-2023 waves of the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). The SIPP has detailed information on the value of the house, financial assets, business ownership, and other non-financial assets, as well as mortgage and other debt. Crucially, it also identifies where the household resides and has sufficient sample size to examine Massachusetts specifically.2

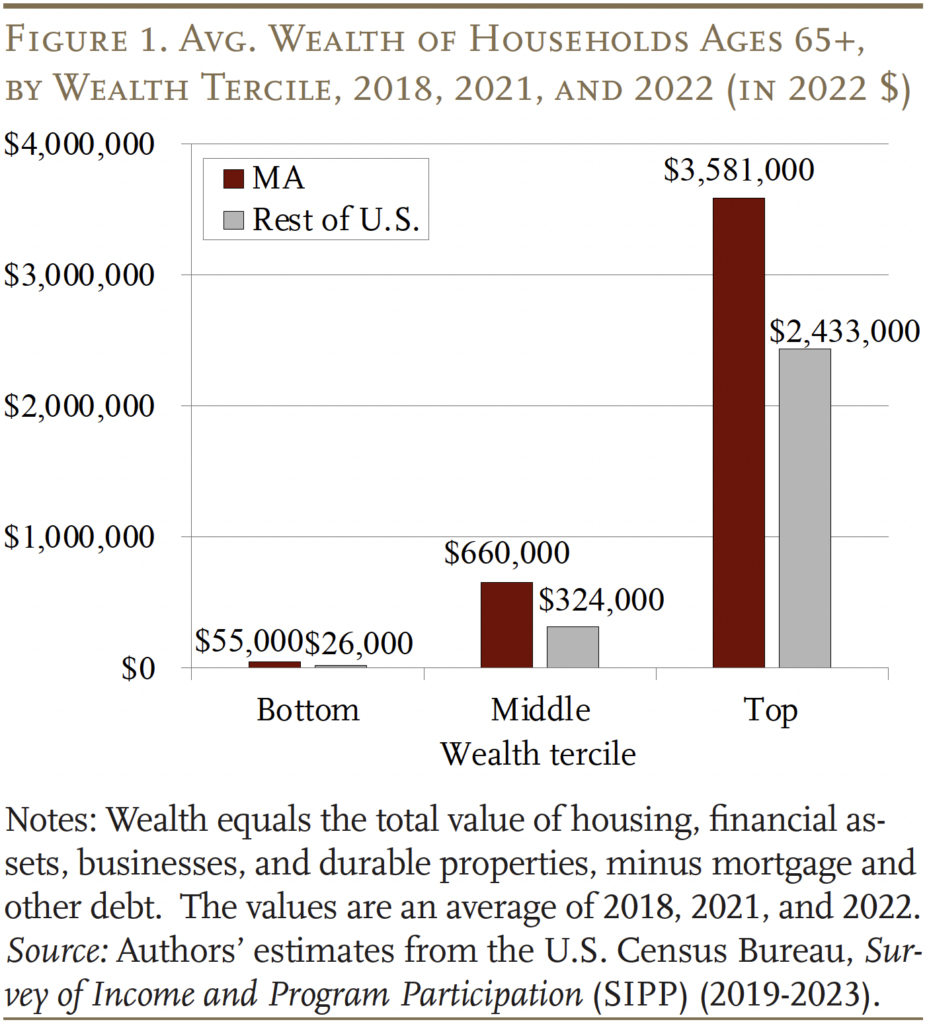

Figure 1 compares the wealth holdings for the bottom, middle, and top third of older households in terms of wealth.3 Two points stand out. First, as expected, older households in Massachusetts are wealthier than their counterparts in other states. Even the bottom third of older households in Massachusetts has twice the resources, on average, as the bottom third in other states. Second, the distribution of wealth is highly skewed, with the bottom third of older households in Massachusetts having just over $50,000, on average, and the top third over $3.5 million.

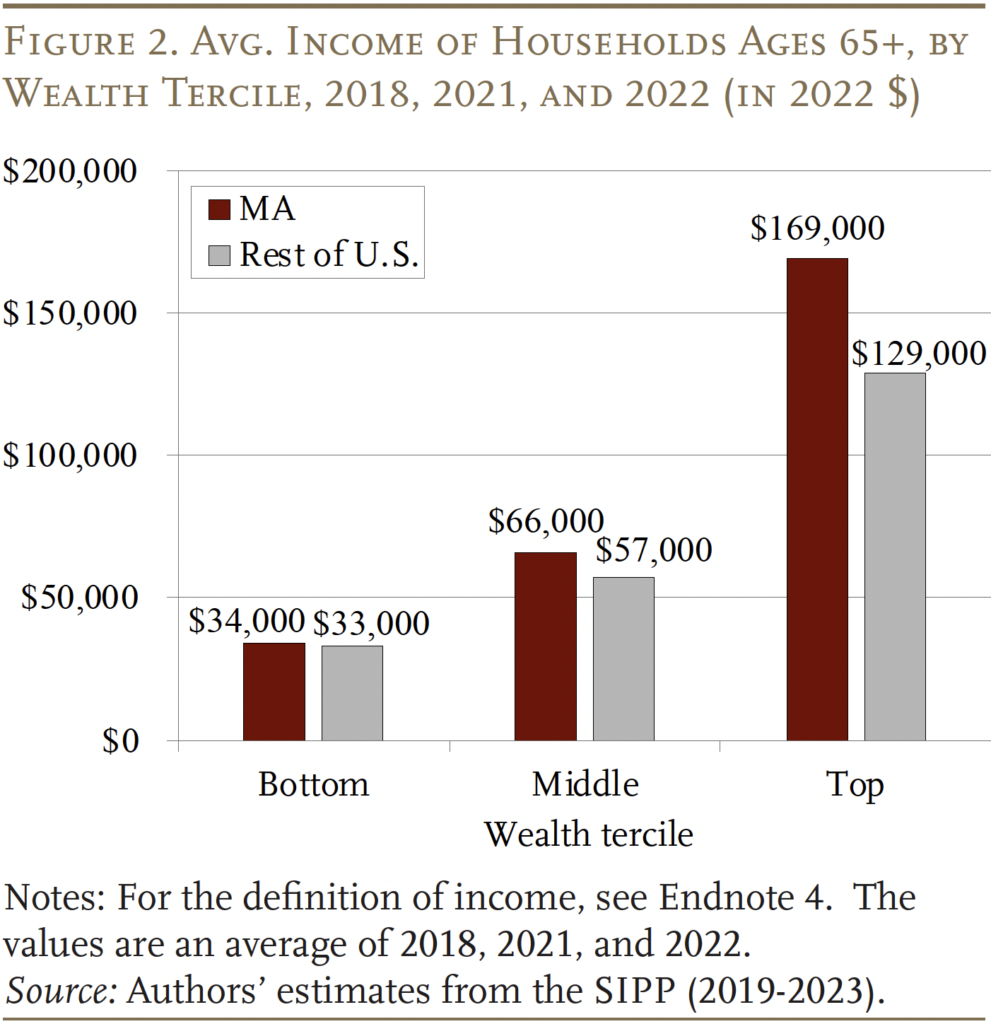

Interestingly, however, large disparities in wealth do not always translate into similar gaps in income (see Figure 2).4 Indeed, while income is also higher in Massachusetts than in the rest of the country, the gaps are relatively modest. For example, older households in Massachusetts in the bottom third have twice as much wealth as their counterparts in other states, but only 5 percent more income.

Cost of Living

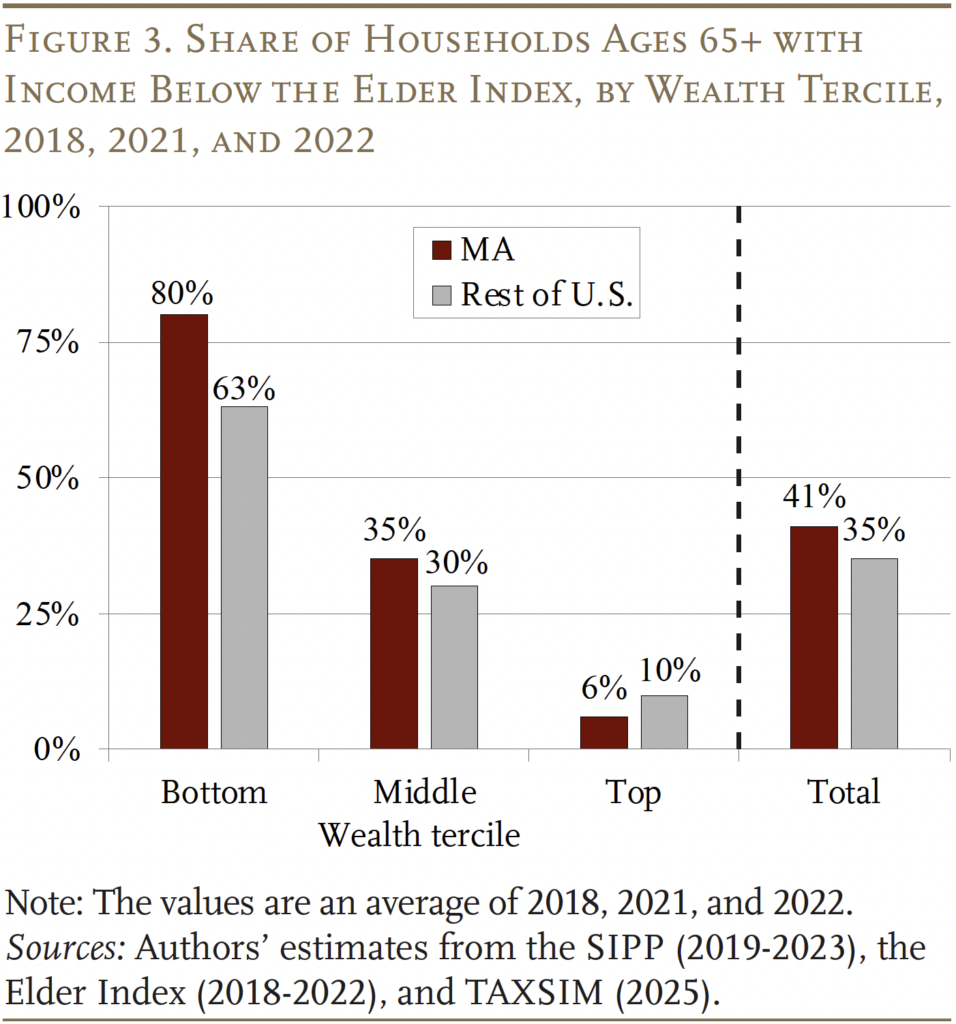

The question is how the high cost of living in Massachusetts affects the well-being of older households. The answer requires comparing each household’s income to a sufficiency budget to estimate the share of households unable to cover basic expenses. The sufficiency budget comes from the Elder Index, which measures the disposable income necessary for a household in a specific county to age in place.5 The budget includes groceries, housing, transportation, and health expenses.6 In addition to geography, the Elder Index varies by marital and home ownership status.

In practice, assessing the share of households falling short requires three intermediate steps. First, since the Elder Index is an after-tax concept, the analysis estimates the federal and state income tax burden faced by each older household in the SIPP and subtracts those taxes from reported income.7 Then, the analysis aggregates the county-level Elder Index up to the state level by taking an average within each state, weighted by the county population. Lastly, the analysis matches SIPP households with the Elder Index based on state, marital status, homeownership and mortgage status, and health. Comparing after-tax income with the Elder Index sufficiency budget yields the share of older households falling short.

Ultimately, Figure 3 suggests that a full 80 percent of low-wealth older households in Massachusetts have insufficient income. In contrast, only 63 percent of low-wealth older households fall short elsewhere in the country. The share drops sharply to 35 percent for middle-wealth households in Massachusetts – not meaningfully higher than other states – and only 6 percent for high-wealth households.

Racial and Ethnic Disparities

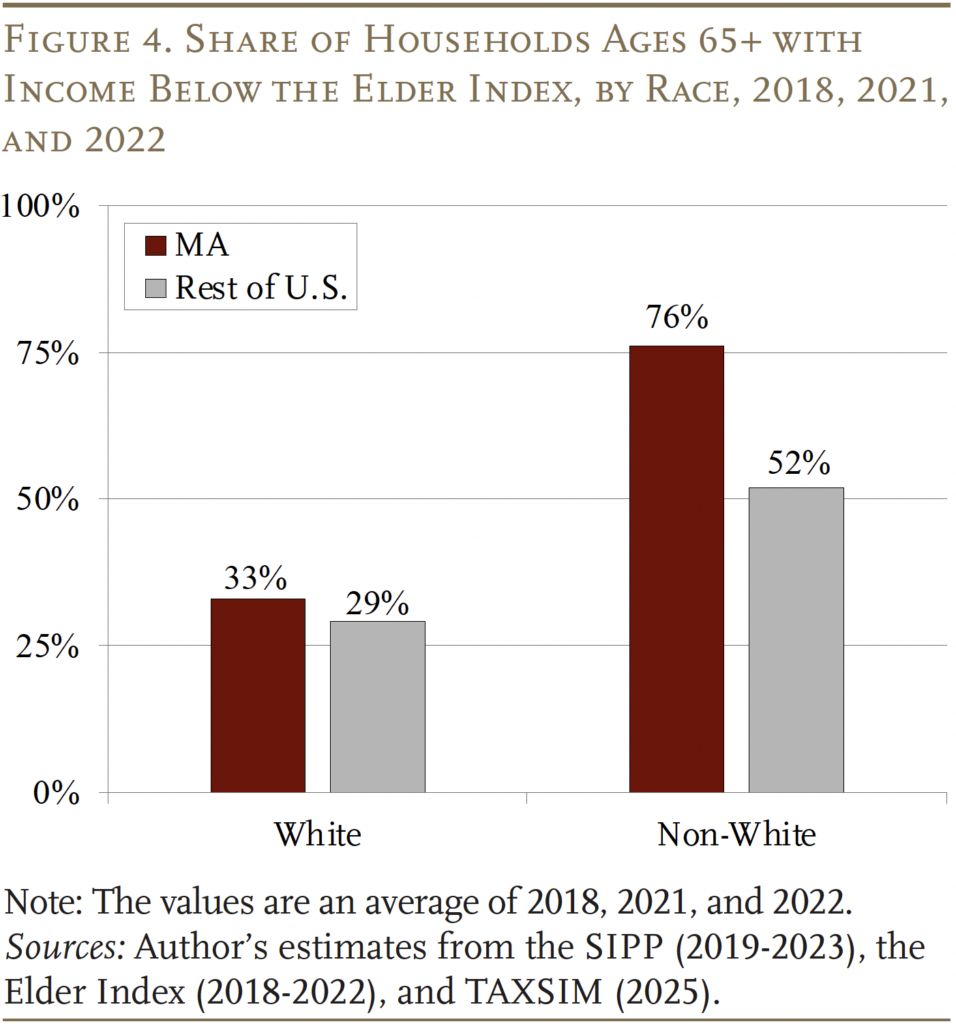

The burden posed by Massachusetts’ high cost of living hits older households of color particularly hard. As shown in Figure 4, about three-quarters of non-White older households in Massachusetts have disposable income below the Elder Index, compared to one-third of White households. This share is much higher than the rest of the U.S., where 52 percent of non-White older households fall short (and 29 percent of White households).

The question, of course, is how low-income older households are able to make ends meet in such an expensive state. The next section explores that question.

Insights from Interviews

While the quantitative analysis documents the financial pressures faced by older households in Massachusetts, it does not capture what life looks like for seniors with little or no wealth or how they make ends meet.

To address these issues, we conducted 29 interviews with low-income (less than $50,000) Massachusetts seniors (ages 65+), living in Boston and its immediate suburbs. The majority of participants (22) identify as Black, three as Hispanic, one as White, and two preferred not to answer. Two participants were men, and the remainder were women. Annual household incomes range from $7,200 to $50,000, with a median of $20,369. Local senior-serving nonprofits provided guidance for interested participants on how to sign up. The interviews were one-hour conversations, either by phone or in person, conducted in English or Spanish. They followed a set of predetermined questions to guide the discussion. Participants were compensated for their time with a gift card.8

Five major findings emerged from the interviews.

1. Many Saw Their Standard-of-Living Decline

The transition from working to retirement brought significant financial and psychological adjustments, as seniors shifted from a period of financial flexibility to one of careful budgeting and restraint. Many described how, when they were working, they spent more freely:

“When I was working, it was different, because I’d spend, spend, spend, spend, spend, I didn’t care, because I knew I had money coming in. But now that I’m not working…I gotta slow down.”

The shift to a reduced income forces retirees to adjust their spending habits, cutting back on non-essential purchases, as one person shares:

“I just retired in December, so I’m just going into being retired. For me, it’s like just learning how to separate spending when I don’t need to spend, only spend when I have to.”

For others, expenses that were once manageable – like dining out or traveling – can become difficult choices, weighed against necessities like housing, healthcare, and utilities. As one person put it:

“I had everything I wanted, everything I needed, or anything I wanted to buy, but, you know, I understand that’s no longer there anymore.”

Retirement is not just a financial adjustment – it is also a shift in mentality. Those who once had financial security but have seen their circumstances change feel a sense of loss, yet are reluctant to accept help. One person described this shift, saying:

“Some people have been on that pedestal and all of a sudden they’re not on the pedestal anymore.”

2. Low-income Seniors Rely Heavily on Social Security

The survey also asked about the participant’s primary source of income. As one would expect, it turned out to be Social Security, given that low-income households are unlikely to have substantial assets or income from employer-based retirement plans.

Among the 29 seniors interviewed, only two currently had savings in a 401(k) plan and one held an IRA. Several others reported having 401(k) savings earlier in life, but said they had been forced to withdraw from these accounts prior to retirement.

“So, when I retired or stopped working for them, I went through what I had in there [in a 401(k)], and that was going back into the early 90s, because I needed it…”

Four participants had a traditional pension from their past jobs or those of their spouse. However, the level of stability provided by the pension varied. One person reported that the pension and the investments by her union gave her good financial stability, receiving health and dental insurance through the union. Other participants were thankful, but noted the limitations:

“I’m not begging, that’s what I’ll say. Sure, I don’t get everything, but I’m thankful. I’m here. I pay my rent out of my pension. I get my food out of my pension. And I pay my light bill out of my pension.”

Given the limited support from retirement plans, the most important source of income was Social Security. Over half of survey participants (17 of the 29) relied on Social Security for 90 percent of their support.9 Many participants had retired early due to disability or other health issues, which means their monthly Social Security benefits were much lower than if they had delayed claiming.

Since Social Security was never intended to be a retiree’s sole source of support, these benefits left many living in a high-cost state coming up short.10 As a result, one participant was working full-time and three were working part-time. One worker explained:

“My income that I get from Social Security, I don’t think is enough for me to pay my bills, for my car, my car insurance, life insurance, all that. I have to work.”

While some turned to work, other participants turned to means-tested benefit programs. While they lamented this shift in lifestyle, they are extremely grateful that these benefits are available:11

“You know, we’re living again, a very subsidized life, and this is what it has come to. It hasn’t always been like that…but these are different times now for us in my health and age, and this is working for us.”

“…for people that really need it, it’s such a blessing to have those kind of resources in place.”

3. Subsidized Housing is Crucial

For many low-income seniors, subsidized housing provides a lifeline, ensuring they can secure stable living conditions and avoid falling into financial distress. One participant explained:

“I must maintain having a roof over my head, because being homeless is not a joke. So my first priority will be making sure, if I don’t do anything else, I make sure my rent is paid.”

At the same time, others find themselves caught in an income gap – earning too much to qualify for low-income housing, but too little to afford market-rate units.

“… why are they making so many units so expensive for seniors? It’s not helping people like myself and others that retire.”

Others described the long and uncertain waitlists for subsidized housing, saying:

“You just have to be hopeful and say, you’re going to get called, you’re going to get picked for the lottery. But, you know, there’s thousands of applications that go into a lottery.”

For the older adults who own their homes, holding onto their property remains critical – not only because mortgage payments may be more affordable than rent, but also because homeownership represents a long-term investment for their families. Several homeowners explained:

“What do I need with a one-family house? But right now, when I pay for my mortgage, it was cheaper than if I go out here and get a one-bedroom…”

“The only thing that kind of throws me off is the real estate bill…not the mortgage, it’s the property tax.”

“I knew when I retired my income would be different, so I wouldn’t want that expense, those expenses, because owning a house, it’s more expensive…property real estate taxes are just…crazy now.”

Ultimately, whether renting or owning, housing remains the single most important financial concern for low-income seniors. For the majority, subsidized housing is a key strategy for maintaining financial stability and meeting basic needs.

4. Support Networks Are Key for Info on Resources

One respondent articulated the difficulties many older adults face in finding and using the resources available in Boston:

“…I became very resourceful in learning what all the resources that Boston [has]…because depending on who we are, and who we know, we may not…have access to all of that…sometimes don’t hear about it, don’t know how to go about it.”

Another participant spoke about how being new to Boston and, as a native Spanish-speaker, not speaking the language made accessing services especially difficult:

“…in the past it was very hard to sign up for benefits. I didn’t have the information, I didn’t know the language, I didn’t know what resources existed, I didn’t know where they were located.”

While Boston has a wide range of resources for seniors, the participant highlights how difficult it can be for older adults to navigate these offerings and access can be contingent on one’s network and social capital.

In the absence of adequate formal assistance, low-income seniors lean on informal networks to share resources. One person described a culture of mutual aid among their peers:

“If it’s something that I don’t want, I share with them, that’s how we do. We share with each other. We swap off. ‘If you want this, take it. If you want that, take it.”

The overarching theme that emerges from these comments is the necessity for more robust support systems that are easily accessible and well-known to those who need them.

5. Family Provide Non-Monetary Support

Retirement often reshapes family roles and expectations, especially for seniors who once provided financial support to loved ones. Some retirees find themselves setting new boundaries, as they can no longer give money as freely as they once did:

“There’s a big difference now…they’re so used to me giving, giving, giving, giving, so now it’s stuck in their head, like, ‘Even if she isn’t got, I’m gonna go ask her.’”

Many older adults highlighted a widespread recognition that younger generations face high housing costs, student loan debt, and other financial challenges, making it difficult to justify seeking their support:

“I don’t reach out to them for anything like that financially, because I know…they’re just making ends meet and with a mortgage and putting a son through college…”

Nonetheless, some seniors do view family as a last resort in emergencies. One person, when asked whether they had emergency savings, responded with laughter:

“Yes and no: my daughter.”

While these older adults prefer to avoid asking for money, many receive support through caregiving, small gifts, or practical help. One older adult described how their daughter provides small but meaningful gestures:

“…sometimes she’ll say, ‘Mommy, here’s an extra $20 or something. Go buy yourself some lunch.’ A lot of the time she’s in the grocery store shopping for her household, and she’ll see things that I might like…”

Another senior emphasized the importance of emotional rather than financial support:

“We do the moral support thing, the family love, the emotional support.”

While few older adults rely on their families financially, these relationships remain a crucial source of stability – through caregiving, emotional support, and the knowledge that family is there if truly needed.

Conclusion

The most powerful tools for improving the financial security of low-wealth seniors are in federal hands, where policies have the broadest reach and scale. But the growing unpredictability of national policy is making state and local action more essential. Massachusetts cannot solve this challenge alone, but it can take meaningful steps to ease financial pressures for today’s older adults and help tomorrow’s retirees build greater stability. Two active policy ideas illustrate how state-level efforts could make a difference.

First, for the seniors we spoke with who do own homes, property taxes – not mortgage payments – emerged as one of their most pressing financial burdens. Massachusetts, like many states, allows qualifying older adults to defer property tax payments for as long as they remain in their homes. This option can free up much-needed monthly cash, but current participation remains low due to complex application processes and restrictive eligibility rules. The Center for Retirement Research recommends three reforms to strengthen the program: 1) eliminate income limits to widen access; 2) simplify enrollment to encourage participation, and 3) shift the financial burden from municipalities to the state to ensure sustainability.12 These changes would make the program more accessible and impactful, helping more older adults stay in their homes without the stress of rising property taxes.

Second, for workers still decades away from retirement, Massachusetts could help close the savings gap by adopting a Secure Choice Savings Program – an automatic IRA for employees without access to employer-sponsored retirement savings. Auto-IRAs are a long-term strategy, unlikely to assist today’s retirees, but they hold enormous potential for increasing future retirement security. Research from the Center finds that a Massachusetts Secure Choice program could significantly reduce the number of workers approaching retirement with little to no savings and would not pose a long-run burden to state budgets.13 Passing this legislation now would be a forward-looking investment, laying the groundwork for more financially secure senior generations to come.

While the state’s relative wealth offers some advantages, its high cost of living and persistent economic inequality create vulnerabilities for many seniors. Addressing these issues will require targeted efforts to improve retirement security and reduce disparities, ensuring that all older adults can age in place with dignity and financial stability.

References

Aubry, Jean-Pierre. 2024. “A Massachusetts Auto-IRA Program.” Special Report. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Aubry, Jean-Pierre and Laura D. Quinby. 2024. “How Does Inflation Impact Near Retirees and Retirees?” Issue in Brief 24-12. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Chen, Anqi, Alicia H. Munnell, and Nilufer Gok. 2025. “Do Households Have a Good Sense of Their Long-Term Care Risks?” Issue in Brief 25-3. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Dushi, Irena, Brad Trenkamp, Charles Adam Bee, and Joshua W. Mitchell. 2025. “Measuring Income of the Aged in Household Surveys: Evidence from Linked Administrative Records.” Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 24(1): 95-112.

Elder Index. 2018-2022. The Elder Index™ [Public Dataset]. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Boston, Gerontology Institute.

Harrington, Kelly, Luc Schuster, and Laura D. Quinby. 2025. “Wealth Gaps in the Golden Years: Economic Insecurity for Older Adults in a High-Cost State.” Report. Boston, MA: Boston Indicators.

Munnell, Alicia H., Wenliang Hou, and Abigail N. Walters. 2022. “Property Tax Deferral: Can a Public-Private Partnership Help Provide Lifetime Income?” In New Models for Managing Longevity Risk: Public Private Partnerships, edited by Olivia S. Mitchell, 231-257. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

National Bureau of Economic Research. 2025. TAXSIM. Cambridge, MA.

U.S. Census Bureau. Survey of Income and Program Participation, 2019-2023. Washington, DC.

Endnotes

- Harrington, Schuster, and Quinby (2025). ↩︎

- Most surveys of household finances have relatively small samples and do not permit analysis of small geographical areas (even states). For instance, the Survey of Consumer Finances and the Health and Retirement Study do not allow researchers to publish results at the state level. The American Community Survey and the Current Population Survey have larger samples but tend to understate retirement income and lack information on wealth (Dushi et al. 2025). ↩︎

- The results in Figure 1 are very similar to the Survey of Consumer Finances (see Aubry and Quinby 2024). ↩︎

- Income includes labor earnings, Social Security, income from investments, defined benefit pensions, withdrawals from 401(k)s and IRAs, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), other government transfers (such as veterans’ benefits), and other private sources (such as transfers from family or friends). ↩︎

- More details on the budget items included in the Elder Index are available at: ElderIndex.org. ↩︎

- The budget does not include expenses associated with long-term services and supports. However, households with low-to-moderate income and wealth primarily rely on Medicaid for these items, alongside informal care from family and friends. See Chen, Munnell, and Gok (2025) for an overview. ↩︎

- Tax estimates rely on the statistical software TAXSIM, developed by the National Bureau of Economic Research. ↩︎

- Our recruitment approach resulted in a relatively narrow participant sample. In part, this was intentional: we focused on low-income Black and Latino older adults, whose financial challenges stood out in the quantitative analysis and whose voices we wanted to center in this qualitative work. At the same time, our sample ended up being narrower than we would ideally prefer. By primarily drawing participants from two nonprofit organizations, we ended up with a group that shares many common characteristics, such as being predominantly Black (76 percent) and concentrated in the southeastern neighborhoods of Boston (76 percent). Because we recruited participants through nonprofits serving older adults, we were more likely to hear from individuals already connected to support networks. As a result, we may have missed perspectives from low-income seniors who are more isolated from these systems or who rely on different coping strategies, such as living with adult children in the suburbs. Our sample also lacks representation from men and older adults over age 80, who may be less likely to participate in community-based recruitment efforts. While the perspectives we gathered offer deep insight into the experiences of a specific and important group, we acknowledge these limitations and note where they may influence our findings. ↩︎

- It became clear that many older adults were unclear about what type of Social Security income they were receiving – retirement, disability, or SSI. ↩︎

- According to our earlier analysis of the Elder Index, Massachusetts seniors in the bottom third of the wealth distribution need at least $39,473 annually to meet their basic living costs, but the average Social Security income for seniors in this demographic is $15,549. ↩︎

- Nearly all the seniors in our sample receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits, MassHealth, and – for transportation – many rely on the RIDE, which is the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority’s paratransit service. Two also received SSI in addition to Social Security retirement or disability benefits. About a third of participants also received some type of housing subsidy. While these benefits help cover basic needs, they do not always ensure true financial security. Family support also helps, but is less prominent than public benefits. ↩︎

- Munnell, Hou, and Walters (2022). ↩︎

- Aubry (2024). ↩︎