Eliminating Tax on Social Security Benefits Is a Supremely Unhelpful Idea

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

That said, the taxation of Social Security benefits could be better designed.

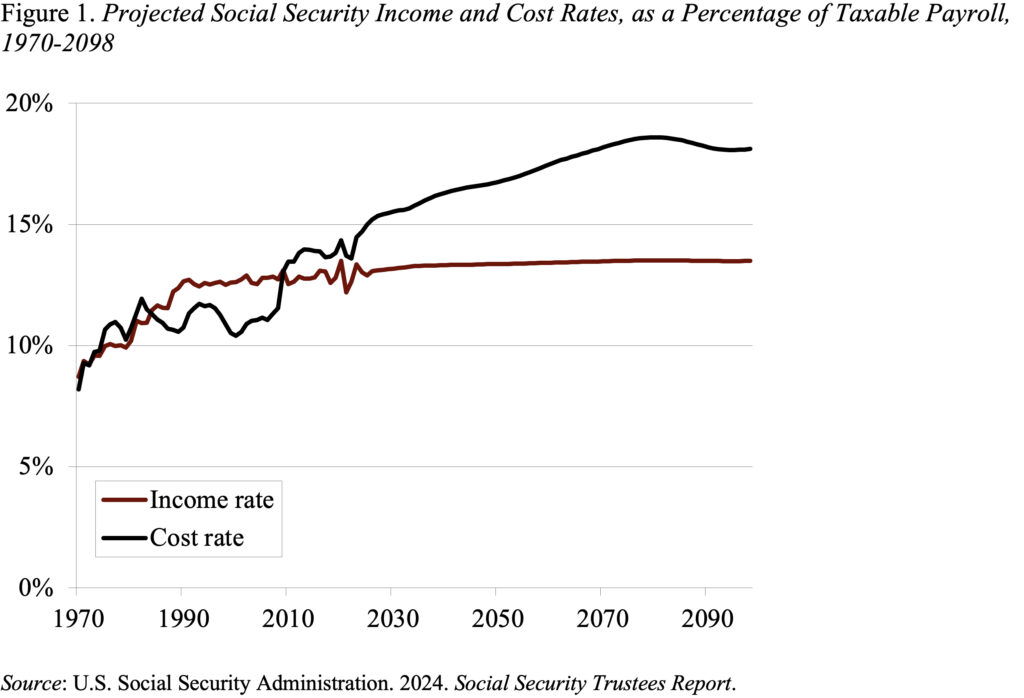

Social Security, the backbone of our retirement system, is facing a financing problem. Costs have been rising and the tax rate has been fixed, creating a gap between money coming in and benefits going out (see Figure 1). In the short term, the government is using the assets in the trust fund – accumulated in the wake of the 1983 amendments – to bridge the gap. Those trust fund assets will be depleted in the first half of the 2030s, and, if Congress fails to act, benefits will be cut by about 20 percent.

To maintain the current level of benefits – a commitment contained in the Republican party platform and supported by Democrats – the system needs more money. So, it is really annoying to hear former President Trump propose to cut the money going into the program by eliminating the taxation of Social Security benefits.

The taxation of benefits, also introduced in 1983, not only produces revenues to cover outlays but also helps make the system more progressive. The benefit structure already replaces a much larger share of pre-retirement earnings for the low paid than the high paid. The taxation of benefits under the federal income tax, which imposes higher rates on those with higher incomes, reinforces this goal.

That said, the taxation of Social Security benefits could be better designed in terms of the nature of the threshold and the share included in income.

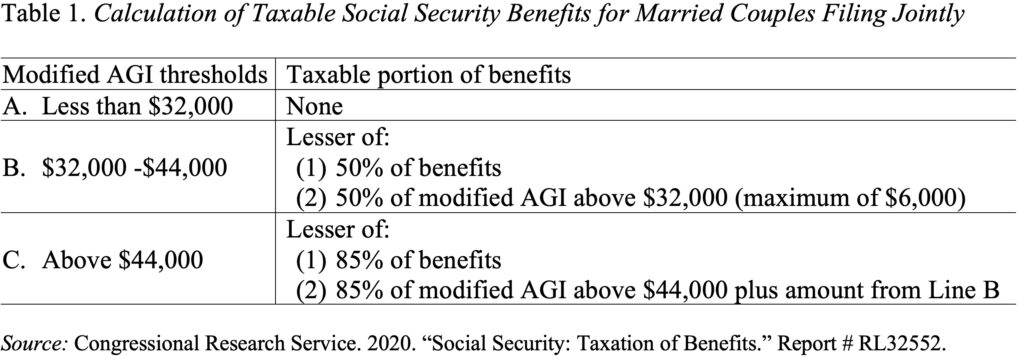

Under current law, married couples with less than $32,000 of modified adjusted gross income (AGI) do not have to pay taxes on their benefits. (“Modified AGI” is AGI as reported on tax forms plus nontaxable interest income, interest from foreign sources, and one-half of Social Security benefits.) Above this threshold, recipients must pay taxes on up to either 50 percent or 85 percent of their benefits (see Table 1).

Unlike the rest of the federal income tax, the thresholds for calculating Social Security taxes are not indexed for inflation. As a result, over time inflation forces many who currently do not pay taxes on their benefits to include 50 percent of their Social Security in their tax calculations and many others who only include 50 percent to pay taxes on up to 85 percent. If policymakers want a threshold, they should select a level below which people do not have to include Social Security benefits in their income and then index that level for inflation. My view is that virtually everything in the policy world should be indexed for inflation.

Second, the benchmark for the current approach to taxing Social Security really does not make sense today. While defined benefit plans offered a reasonable benchmark in the 1980s, today most private sector workers are covered by 401(k)s. Since 2006, when Roth 401(k)s became available, taxes can be levied in two ways. In the traditional 401(k), the employee puts in pre-tax dollars and is taxed when the money is withdrawn in retirement. In the Roth 401(k), the employee puts in after-tax dollars and pays no tax in retirement. Social Security contributions can be thought of as one-half traditional and one-half Roth. From this perspective, taxing Social Security like private plans would suggest that the half of Social Security benefits financed by the employer’s pre-tax contribution should be taxable in retirement and the Roth-like other half, where taxes have already been paid, should be excluded. In other words, today 50 percent – not 85 percent – of Social Security benefits might be viewed as the appropriate share of benefits to include in adjusted gross income.

In short, a thoughtful reconsideration of the taxation of Social Security benefits could be included in any process to solve Social Security’s 75-year financing shortfall. But coming out with a one-off proposal to eliminate all taxation of Social Security benefits is supremely unhelpful.