Great Recession Cut Late Boomers’ Retirement Wealth

The baby boomers born in the early 1960s, at the tail end of the demographic wave, had about $280,000 in retirement wealth when they reached their early 50s. That’s significantly less – about $50,000 less – than the late-1950s boomers had at the same age.

Some of this shortfall might’ve been anticipated for the youngest boomers. Each new crop of boomers has taken a bigger hit in their Social Security checks because the statutory age for collecting the full monthly benefit has been creeping up. The shrinking checks are against the backdrop of dwindling pensions. (Retirement wealth includes the current value of worker’s future Social Security and traditional pension benefits, as well as retirement savings.)

But, while Social Security and traditional pensions are smaller, the decline in late boomers’ wealth overall was not preordained. They were the first generation to have access to a 401(k)-style retirement plan for their entire careers, and they could’ve accumulated enough money in savings to make up for the other losses. But they didn’t.

The single biggest reason for the shortfall in savings was the 10 percent spike in unemployment during the Great Recession that followed the stock market crash, finds a new study that separates out the economic and demographic reasons behind the decline in late boomer households’ wealth.

The unemployed were forced to reduce contributions to employer retirement accounts, and the financial damage was worse for the late boomers than for the people born earlier in the baby boom. The “link between work and wealth accumulation declined significantly for late boomers, compared to mid-boomers,” the researchers explained.

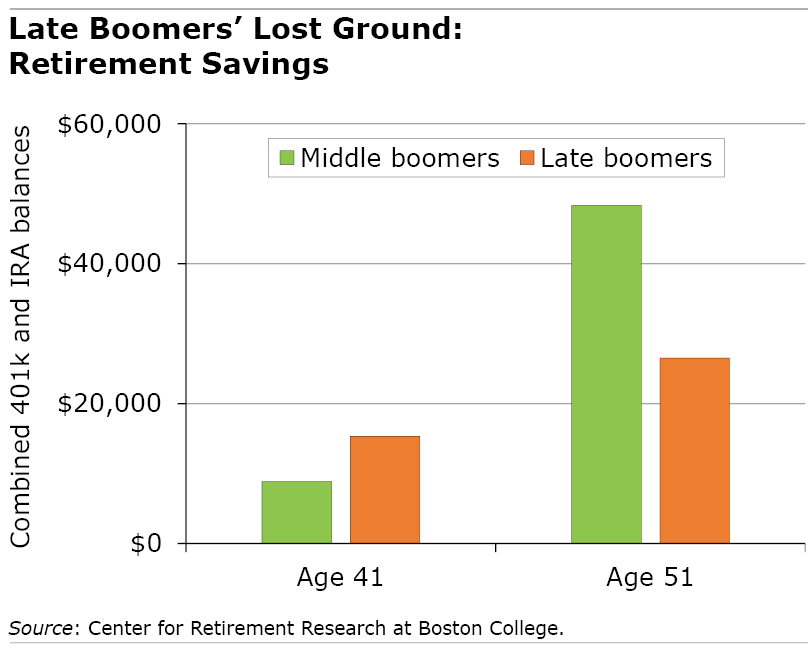

Prior to the Great Recession, the late boomers were ahead of the workers who were born earlier in the boom. At age 41, late boomers had $15,329, on average, in their 401(k)s and IRAs – substantially more than the middle boomers born in the late 1950s had saved by that age.

But after the recession, the tables had turned. By age 50, late boomers had around $28,000 in savings – half of what the mid-boomers had at 50.

The weak labor market took its toll in two ways. The late boomers’ employment rate, which had been 98 percent before the Great Recession, dropped below 80 percent a decade later and stayed there for several years. Those newly unemployed workers lost the ability to save in a 401(k) or may even have been forced to withdraw money to pay bills.

The recession did not spare the late boomers who remained employed either, and their 401(k)s took an indirect hit. Income tends to level out or decline around age 50, but the late boomers’ incomes fell sharply in their 40s, which are usually the peak earning years. At 50, their household earnings averaged around $73,000, compared with $104,000 and $88,000, respectively, for early and mid-boomers at 50.

Smaller paychecks translate to smaller 401(k)s, because some people stop contributing altogether. If workers do keep up their regular 401(k) contributions, the amounts are smaller because contributions are a set percentage of a worker’s earnings.

Demographic changes have also reduced late boomers’ average wealth accumulation but to a lesser extent. People of color have vastly less wealth than Whites, and the Hispanic and Black populations have grown, so as the retired population becomes more diverse, average balances look smaller.

However, the wealth gap between workers of color and White workers actually narrowed, mostly because their Social Security wealth increased.

The main culprit in late boomers’ misfortune was the Great Recession – and that may be good news for the generations that follow. As the economic calamity recedes in the rear-view mirror, “some of the downward pressure on wealth holdings should abate,” the researchers predicted.

To read this brief by Anqi Chen, Alicia Munnell, and Laura Quinby, see “What Happened to Late Boomers’ Retirement Wealth?”

The research reported herein was derived in whole or in part from research activities performed pursuant to a grant from the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the opinions or policy of SSA, any agency of the federal government, or Boston College. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof.