High Fees Hurt Public Plan Funding

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Fees are in the news. CalPERS plans to cut the number of money managers in half, and drop its hedge funds. New York City is on a rampage about fees eating into its pension plan returns. And the Governor of Pennsylvania is calling on the state’s two pension systems to reduce investment manager fees.

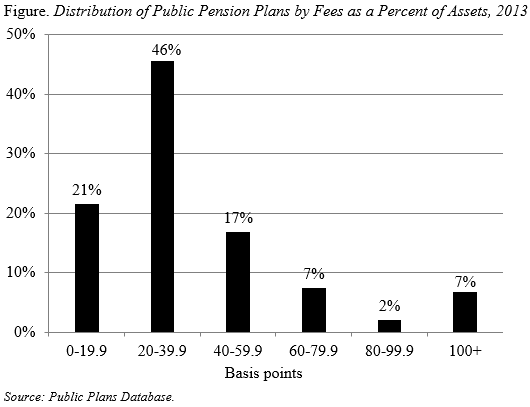

The Figure shows the distribution of plans by fees paid, where fees are measured as basis points of assets under management. The fee ranges from under 20 basis points (0.2 percent) to more than 100 basis points (1.0 percent). Average asset weighted fees in 2013 were 40 basis points.

The Chief Investment Officer of CalPERS, the largest public pension plan in the country, announced a plan to lower fees, risks and complexity by reducing the number of direct relationships with private-equity, real estate and other external funds from 212 to 100 over the next five years. In 2013, CalPERS’ fees amount to 102 basis points, making it a very high cost plan. Moreover, press reports suggest that the reported number does not include the carry interest cost and performance costs associated with private equity investment. CalPERS had earlier (September 2014) eliminated its hedge fund program in an effort to reduce both the complexity and costs in its investment portfolio.

In Pennsylvania, the Governor is shining the spotlight on fees to help improve the funded status of the state’s pension plans. In 2013, Pennsylvania Public School Employees Retirement System paid fees of 114 basis points and Pennsylvania State Employees Retirement System 66 basis points. It’s important to note that Pennsylvania not only pays high fees but also have been among the poorest in making the annual required contribution.

One could argue that California and Pennsylvania were earning extraordinary returns in exchange for the high fees. But an analysis released by New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer suggests this may not be the case. The analysis found that high fees and the failure to hit investment targets had cost the New York City five pension funds $2.5 billion over the last decade. As a result, the City plans overhaul how it engages with investment managers to ensure that fees and value are better aligned.

Are fees really important? Yes, reducing fees would have a noticeable effect. CalPERS and the Pennsylvania plans had fees over 100 basis points in 2013. The average for the 150 plans in our sample is about 40 basis points. If high-fee plans could do away with that 60 basis point difference, over a 30-year period their assets would be about 18 percent higher. That would raise the funded status of CalPERS from 75 percent to 88 percent and Pennsylvania plans from around 60 percent to 71 percent. So reducing fees is not a solution to the funding problems, but a step in the right direction.