How Are Public Pensions Faring with Falling Markets and Rising Inflation?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Mitigating factors make adverse developments bearable.

My colleague, JP Aubry, just released an update on the state of public pensions in the wake of falling markets and rising inflation. Despite the recent alarm about the impact of lower asset prices and higher inflation on pension finances, his assessment is relatively sanguine.

Admittedly, fiscal year 2022 has been difficult for state and local pension plans, with large losses in both stocks and bonds. But this experience has to be considered against the background of 2021, when pension funds enjoyed outstanding investment returns, as well as federal COVID-19 relief and tax revenue windfalls that helped governments make their required pension contributions.

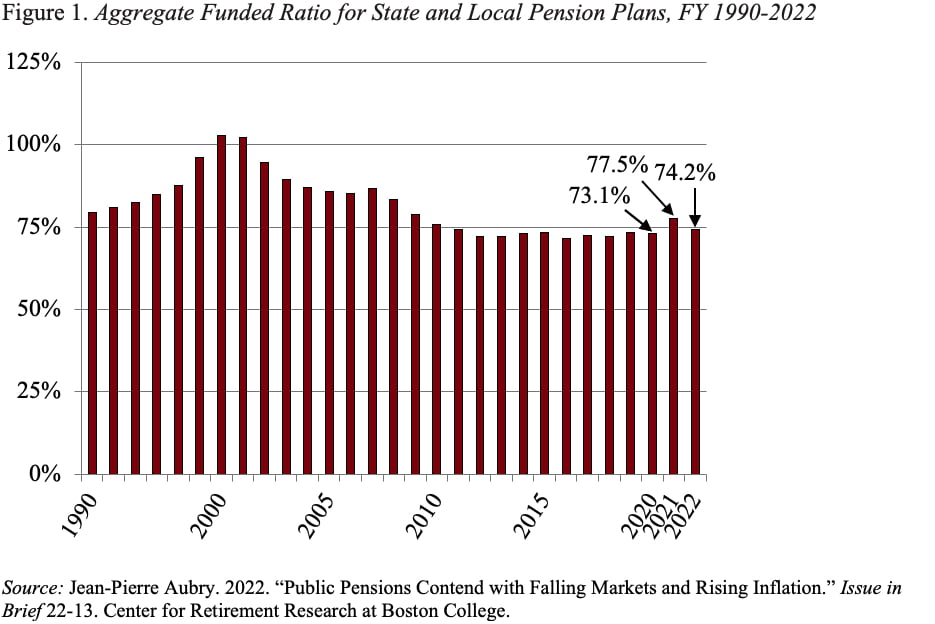

Data for 2021 and projections for 2022 suggest that the aggregate actuarial funded ratio rose by 4 percentage points in 2021 and decreased by 3 percentage points in 2022 (see Figure 1). While the rise and fall tracks with stock market performance over this period, the impact of market fluctuations is muted significantly due to actuarial smoothing techniques used when reporting actuarial assets. Nevertheless, the bottom line is that the market declines erased some but not all the gains from 2021.

On the other hand, public plans face the new challenge of higher future outlays due to inflation. The Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers, in June 2022, rose at a 12-month pace of 9.1 percent – a rate not seen in four decades. Inflation puts direct pressure on public pension finances because, unlike defined benefit plans in the private sector, these plans provide some form of cost-of-living adjustment (COLA).

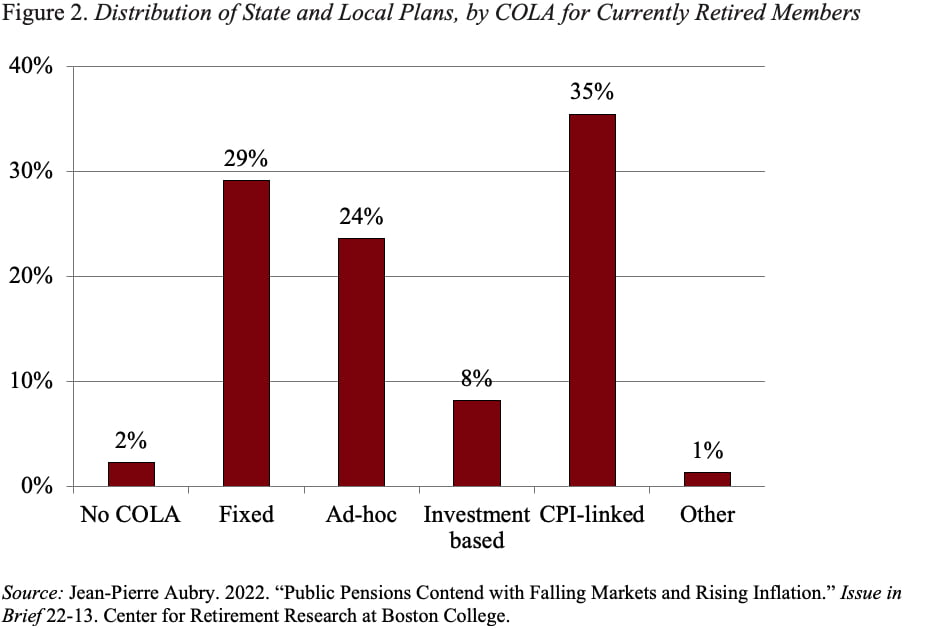

Here too, however, JP cites mitigating factors. Most plans – especially in the wake of the Great Recession – have placed limits on their COLAs. Currently, just over a third of public plans provide CPI-linked COLAs to their current retirees (see Figure 2). The others provide either a modest “fixed rate” adjustment not linked to the CPI, an intermittent “ad hoc” adjustment not necessarily linked to the current rate of inflation, or an “investment-based” adjustment tied to some financial metric, such as the plan’s overall funded level.

Importantly, of the plans offering automatic CPI-linked COLAs, less than 10 percent provide complete inflation protection. Thus, the vast majority of plans with CPI-linked COLAs cover only a portion of annual inflation increases and/or place caps on the maximum COLA. On average, CPI-linked plans guarantee about 85 percent of the CPI increase up to a maximum of 3.5 percent.

Of course, the flip side of limited COLAs is that high inflation erodes the purchasing power of retiree pension benefits. If the burden on retirees becomes too great, pressures could build to provide greater inflation protection – which would cost plans more. But as things stand now, inflation should not cause major problems for state and local plans.