This Is How the Republican Healthcare Bill Will Affect the Elderly

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Under the American Health Care Act, states will bear a growing burden of the health costs for an aging population.

Most people are focused on the Congressional Budget Office’s scoring of the American Health Care Act (AHCA) that is designed to repeal and replace Obamacare. But retirement’s my game, so I’m interested in how changes in legislation will affect the elderly. So, I did what I usually do; I asked my colleague Melissa McInerney, a Tufts University economics professor and health expert who is visiting the Center this year.

She said the component of the legislation that restructures Medicaid would impact the nearly 7 million people ages 65 and over enrolled in the Medicaid program. For these low-income seniors, Medicaid covers Medicare cost-sharing (such as premiums and deductibles), services that Medicare does not cover (such as vision and hearing), and – most importantly – long-term care.

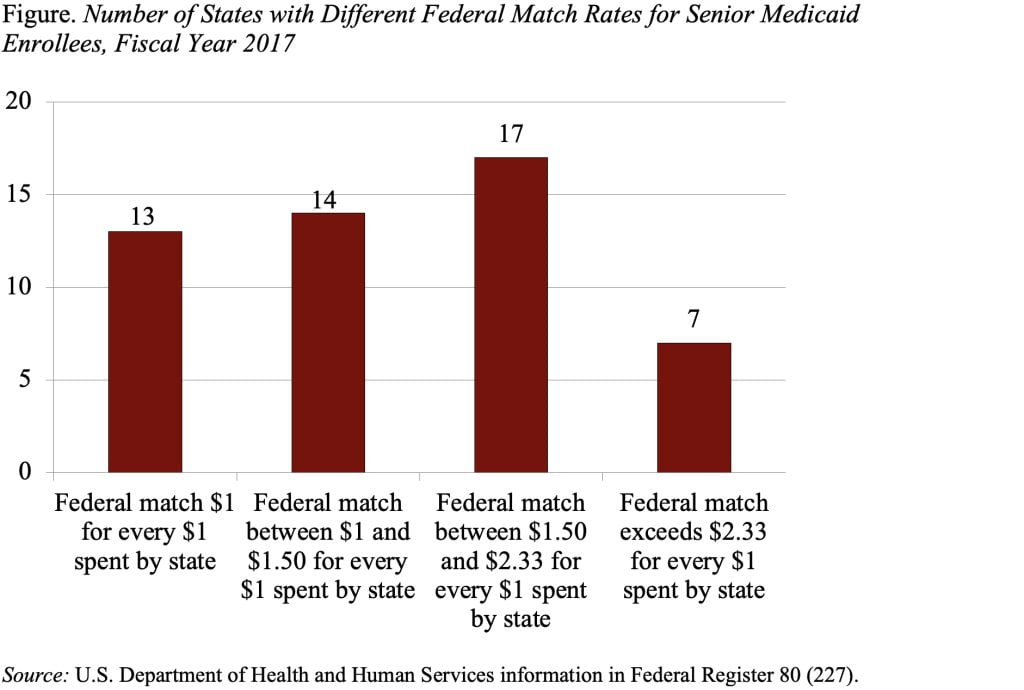

Under current Medicaid arrangements, states and the federal government share in the financing of benefits. For example, in Massachusetts, the federal government matches the state’s Medicaid spending dollar for dollar. In poorer states, the federal government matches up to $2.94 for every dollar spent by the states. The figure shows the number of states with various matching rates.

The AHCA will replace the matching arrangement with a set amount per enrollee. These amounts will vary across states, so that states that had higher Medicaid costs in the past receive higher amounts from the federal government. And the federal contribution per enrollee will be higher for groups with higher medical costs, so that the payments for seniors or adults with disabilities will be larger than those for children, whose medical costs are typically lower.

But even with these adjustments, the burden on states is very likely to increase over time as the needs of senior Medicaid enrollees change. For example, as the Baby Boomers grow older, the average age of the senior population will rise. An older population means a greater need for expensive services like long-term care, driving up the average per capita Medicaid costs for seniors. However, the federal contribution will be based on historic state spending on seniors. In addition, the federal payments will only be adjusted by changes in the medical component of the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which reflects spending on the general U.S. population – young and old, healthy and sick. For both these reasons, the costs of insuring seniors are likely to grow faster than the federal payments for seniors, leaving the state responsible for an increasing share of Medicaid costs.

Since the cost of insuring seniors and adults with disabilities already comprises 63 percent of Medicaid costs, the ACHA will leave states responsible for a large amount of Medicaid spending. This outcome is very different from the current system, where any increase in state Medicaid spending would be matched at least dollar for dollar and in many case by a higher rate.

How will states respond? They could reduce enrollment, limit benefits, or pay providers less. Any one of these responses would be harmful to seniors who receive support from the Medicaid program.