How Has the Decline in Assumed Investment Returns Affected Public Pension Costs?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Much less than you would think.

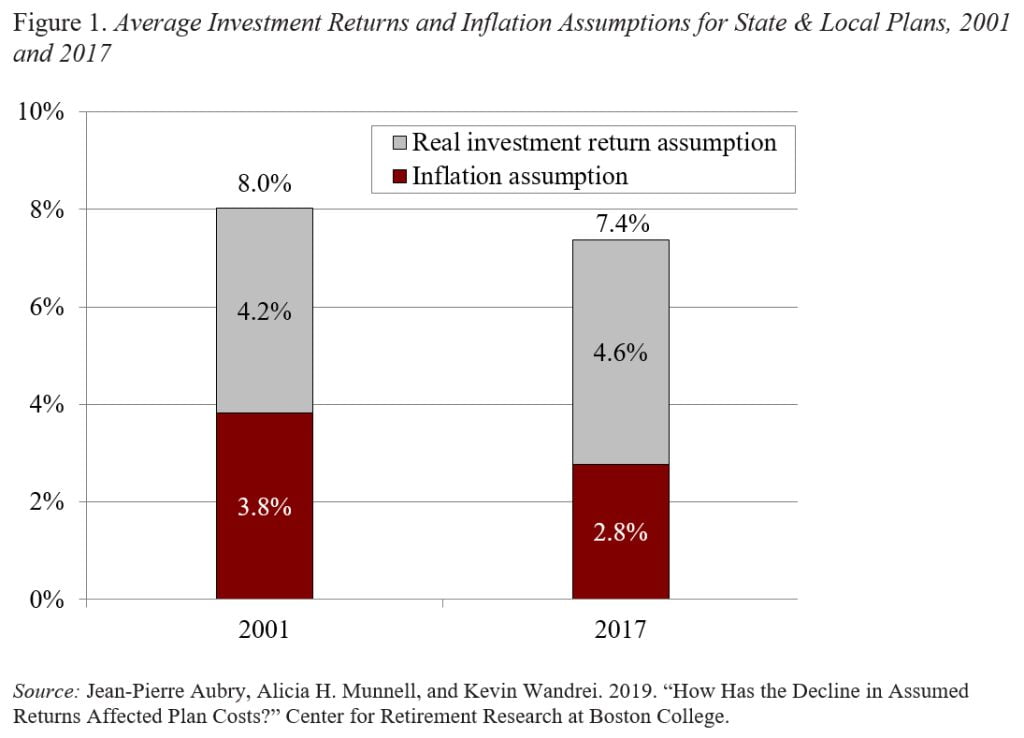

Many state and local pension plans have lowered their long-term investment return assumptions in the wake of the financial crisis. Such a change is generally viewed as a positive development for pension funding discipline, bringing assumptions more in line with market expectations and forcing plan sponsors to increase annual required contributions. A study recently released by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College shows in this case, however, the decline is actually due to lower assumed inflation, not a lower real return (see Figure 1).

In a fully-indexed system where benefits fully adjust with inflation, a lower inflation assumption should actually have no impact on costs. Yes, lower nominal returns will produce less revenue. But, lower inflation will also decrease initial benefits (through lower wage growth) and the cost-of-living-adjustment (COLA) paid after retirement.

At the same time that plans have lowered their inflation assumption, they have changed their asset allocation and increased their assumed real return from 4.2 percent to 4.6 percent (again see Figure 1). A higher real return – all else equal – lowers costs. Therefore, a quick assessment of these underlying assumption changes suggests that plans may have actually lowered their costs with the decline in the assumed return.

But, while public plans may seem like fully indexed systems because they provide benefits based on final earnings and offer post-retirement COLAs, they are not. In reality, not all benefits are based on final earnings, and most COLAs are not designed to fully compensate for inflation.

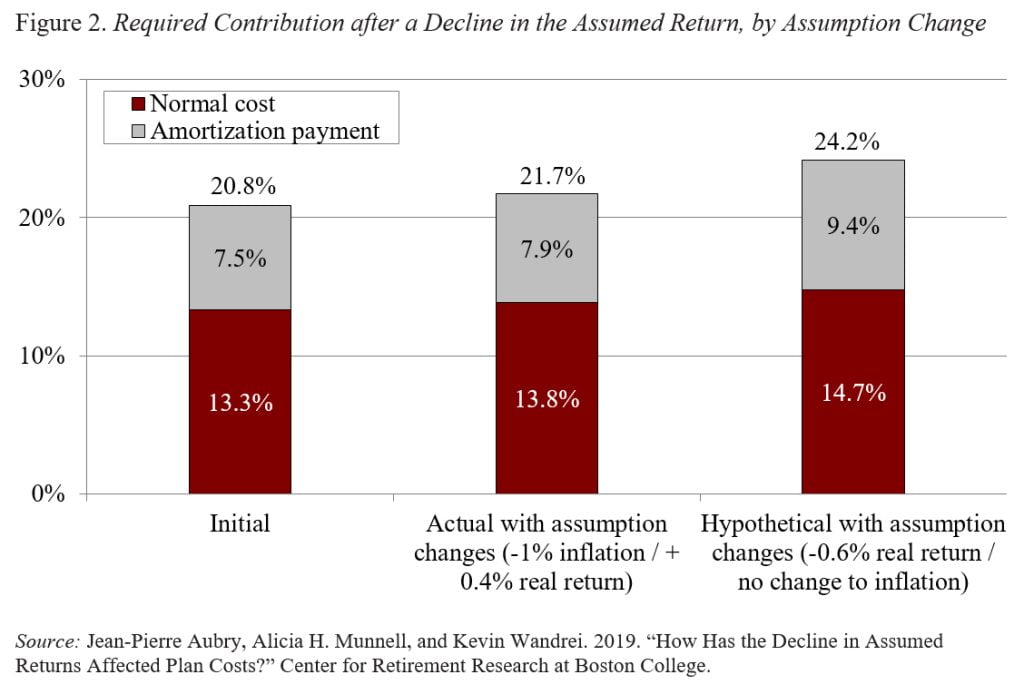

Because benefits before and after retirement are not fully linked to inflation, they do not decline one-to-one with lower inflation. Thus, as inflation assumptions drop, costs increase. What is the overall impact of these opposing dynamics? In 2010, when plans began to lower their assumed returns in earnest, the required contribution for plans was 20.8 percent – 13.3 percent of payroll for normal cost and 7.5 percent of payroll for the amortization payment (see Figure 2). The changes in the underlying assumptions that have resulted in the lower assumed returns – the 1-percentage-point decrease in inflation and the 0.4-percentage-point increase in the real return – would have raised the required contribution by 0.9 percent of payroll (20.8 percent to 21.7 percent). But, under a hypothetical scenario in which lower assumed returns are instead driven by a reduction in the assumed real return, the increase in the required contribution would be more than three times as high at 3.4 percent of payroll (20.8 percent to 24.2 percent).

In short, lower inflation and a higher real return increased costs, but the increase was much smaller than if the decline in the assumed return was due to a lower real return.