Increase the Retirement Age, but Only for Those Who Can Work Longer

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Let’s see if we agree on what the retirement age is today.

With the projected depletion of the Social Security trust fund assets in the 2030s, policymakers are looking for ways to bridge the gap. One of the major proposals is to increase the retirement age. Certainly, with average life expectancy increasing, longer careers could be one way to ensure an adequate retirement with less reliance on Social Security.

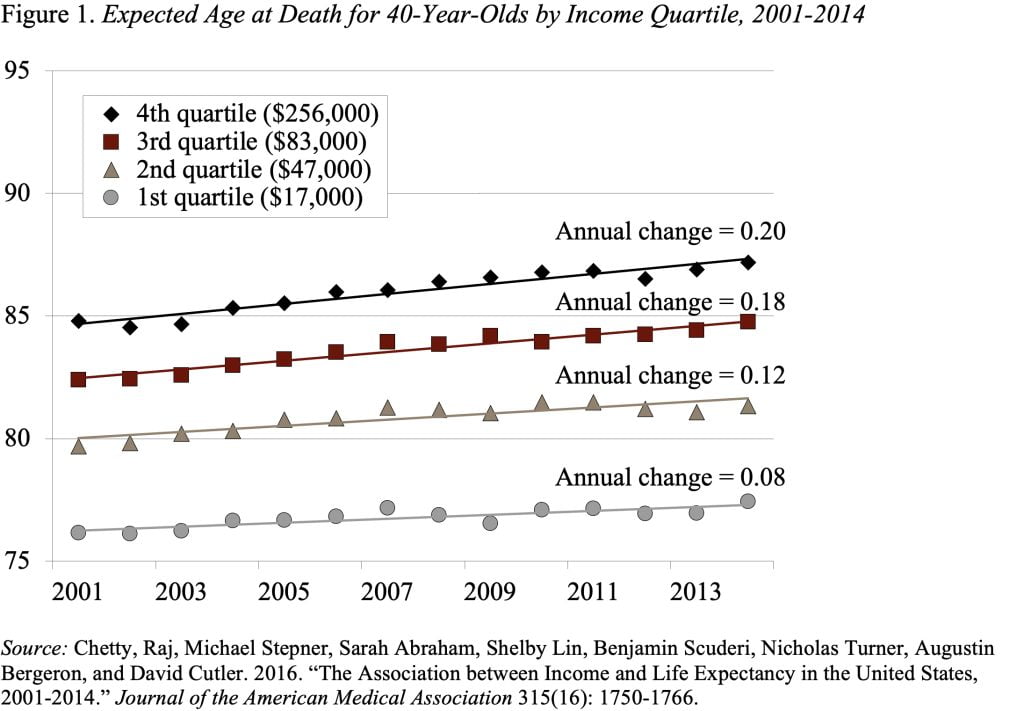

The problem is that life expectancy varies significantly across the income spectrum, and the gains in life expectancy have been much greater for the wealthy than for the poor (see Figure 1). Thus, increasing the retirement age across-the-board for all workers should be a non-starter. But incorporating later retirement into the system where possible may avert sweeping changes that could do harm to the vulnerable.

Before we do anything, however, we need to at least agree on the retirement age in the current Social Security system. Today workers can claim their benefits any time between 62 and 70. Benefits claimed before age 70 are actuarially reduced, based on average life expectancy. In other words, the claiming age affects monthly benefits but, on average, is intended not to alter total benefits paid over the lifetime.

Despite the fact that 70 is the age at which Social Security pays the highest benefit, the policy conversation focuses on raising the “Full Retirement Age” (FRA), which used to be the age at which workers received the highest lifetime benefits. For a long time, the FRA was 65, but the 1983 Social Security amendments increased the FRA from 65 to 67 over a 23-year period. The increase to age 66 was phased in between 2000 and 2005, followed by an 11-year hiatus, and from 66 to 67 between 2017 and 2022.

Many suggest moving the FRA higher. Raising the FRA, however, is not just a question of “postponing” claiming for those who can work longer; it is a benefit cut. For example, compared to when the FRA was 65, those who are able to delay retirement to 67 receive two years less of benefits and those who cannot adjust their retirement behavior get lower benefits due to the increased actuarial adjustment. Importantly, those forced to claim at 62 used to receive 80 percent of the full benefit, but now they receive only 70 percent. If the FRA were increased to age 70, that amount falls to 55 percent. So, changing the FRA is a blunt instrument that affects both those who can work longer and those who cannot.

We need a different approach. We need to identify the guys who are going to end up in the fourth quartile of the income distribution and change the rules so they must work longer to get their current benefits. The question is how to do that operationally. One option is to simply use, say, the highest 10 years of average indexed earnings to identify the winners. But since the final score is not absolutely clear till the end of the game, such an approach may not leave workers with enough time to plan wisely. An alternative is to identify the retirement age based on factors that occur early in life, such as level of education – the evidence suggests that college graduates have the ability to retire much later than those without a college education.

The important point is that the population is not homogenous. The more privileged in our society are living longer and healthier lives; but the majority have not seen great gains in life expectancy, much less in healthy life expectancy. Let’s be clever here and raise the retirement age for those who can work, without doing any further damage to those who cannot.