Is Job Automation Connected to Disability?

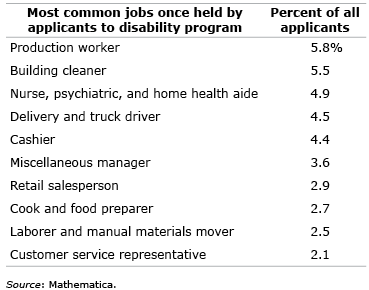

Manufacturing workers file more applications to the federal disability program than any other workers. What seems new is that jobs like administrative assistant and retail worker aren’t that far behind.

Is one possible explanation that the computerization of once-routine occupations like these plays a role in decisions to apply for disability benefits?

Consider the example of a retail worker with a bad back who is laid off, or perhaps she quits because she struggled to handle the cognitive challenges of increased automation. Even simple tasks such as processing customer transactions or locating a product at another store now require computer skills. And the worker’s skills may not match up with the technical qualifications needed to find a new job in a labor market where routine jobs are rapidly disappearing.

Given her disability, the worker might decide that her best – or only – option to ensure she has some income is to apply for disability benefits.

A study by Mathematica researcher April Yanyuan Wu did not find direct evidence that this skills mismatch triggers applications. But her findings suggest it might be a factor.

Wu provided new statistics on the types of jobs once held by disability applicants and on the changes over time in the job attributes, compared with the changes in job attributes facing the general working population.

Between 2007 and 2014, for example, the share of the applicants’ former jobs that required computer skills rose by 18 percentage points, outpacing the increase for the labor force overall. At the same time, jobs requiring moderate cognitive ability also increased more for people with disabilities than it did for all workers.

Stress is a telling indication of the challenges of increased job automation. The growth in high-stress jobs once held by people with disabilities was much larger than for workers overall, according to the study, which was funded by the U.S. Social Security Administration.

Finding ways to help workers with disabilities transition to other jobs would be one way to address this problem, Wu said.

To read this study, authored by April Yanyuan Wu, see “In What Occupations Did SSDI Applicants Work? New Statistics and their Implications for Policy.”

The research reported herein was derived in whole or in part from research activities performed pursuant to a grant from the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium. The opinions and conclusions expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the opinions or policy of SSA, any agency of the federal government, or Boston College. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, make any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof.