Low Fertility Is a Really Big Problem – with an Easy Answer

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Giving money to new parents won’t fix the issue.

In recent weeks, the government released provisional data for 2024 that show the birth rate remains low in the U.S., and reports suggest that the Trump administration wants to encourage Americans to get married and have more babies.

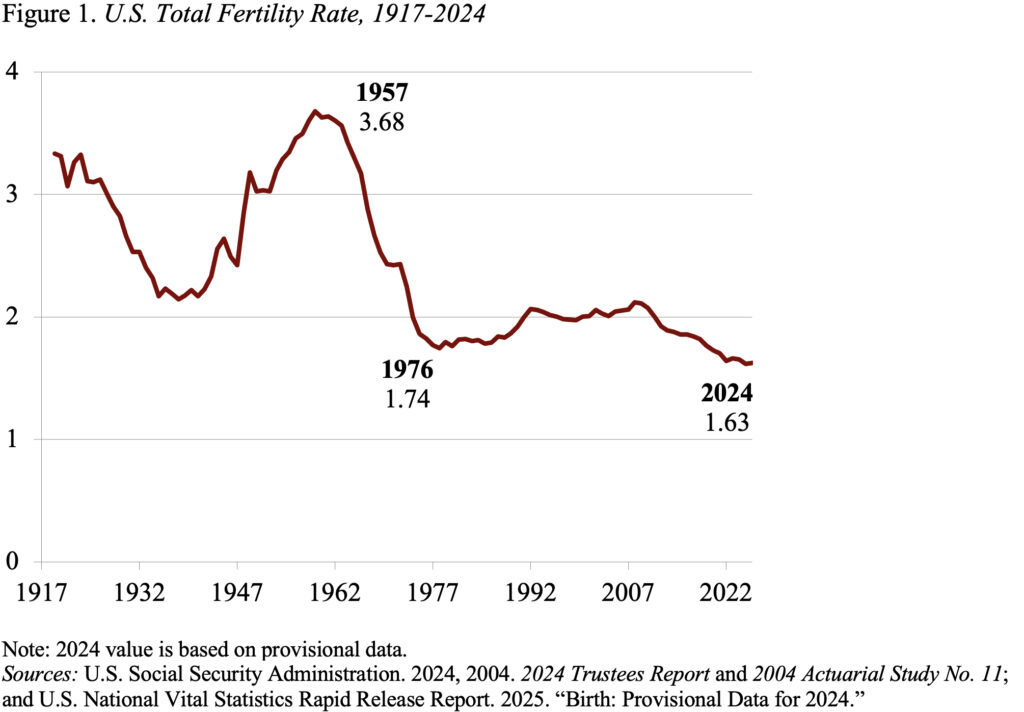

First the facts. Fertility rates have generally been falling since the end of the baby boom in the mid-1960s, and that decline accelerated after the Great Recession. Many observers thought that once the economy recovered, the fertility rate would rebound. It has not (see Figure 1). Today, the hypothetical lifetime number of births for a woman over her childbearing years is 1.63, well below the level required to hold the population steady.

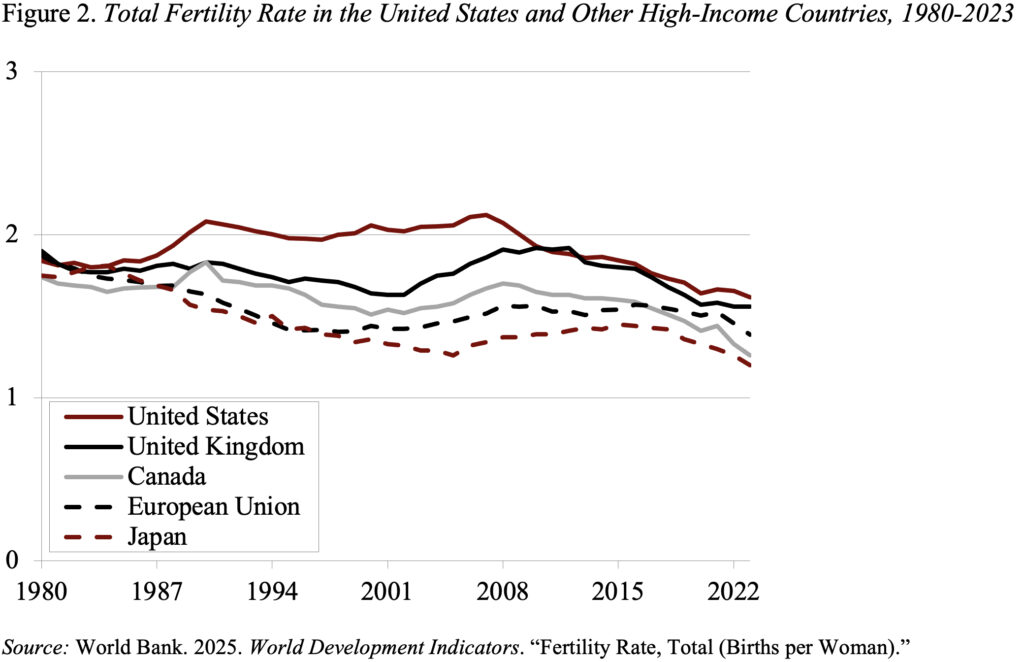

The U.S.’s current fertility rate is not an anomaly; it is roughly in line with the rates in other high-income countries (see Figure 2). Part of the belated convergence reflects a dramatic decline in births among Hispanic women, some of which can be attributed to an increase in the native-born share of Hispanics and some may reflect the declining birth rate in originating countries such as Mexico. The important point is that we should not expect the U.S. rate to rebound in the foreseeable future. (For a great summary of the state of play on the fertility rate see a recent paper for the Aspen Institute by Melissa Kearney and Phil Levine.)

Is low fertility a problem? Some people think it’s a positive reflection of women’s ability to control their own destiny. Indeed, women have gained enormous ground in educational attainment and workplace opportunities.

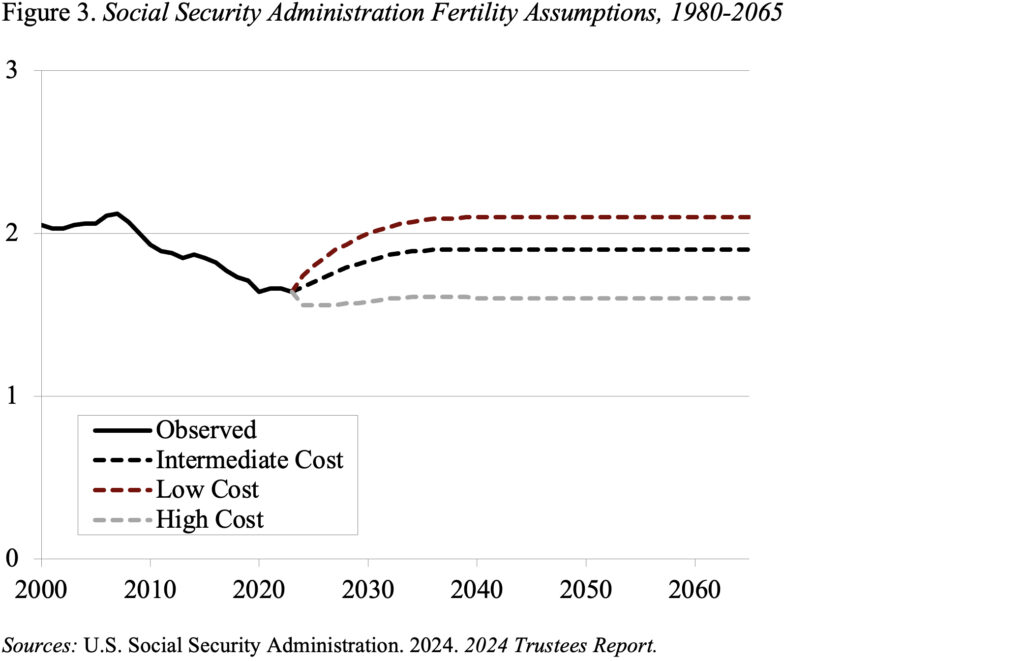

But low fertility does have real economic consequences as well. It can lead to less innovation and slower economic growth. It can also create fiscal problems. And for those of us interested in retirement, a major concern is the impact of low fertility on Social Security and Medicare, both of which fund benefits to retirees through taxes on workers. Although the Social Security Trustees have reduced long-run fertility assumptions somewhat, they still remain significantly above current rates (see Figure 3).

What can be done? Rumor has it that fertility issues will become “a prominent piece” of the administration’s agenda. President Trump has called for a “baby boom,” and JD Vance, as well as Elon Musk, are clear pro-natalists. Some of the ideas in the mix for increasing fertility include a $5,000 cash “baby bonus” to every (married I presume) American mother; reserving Fulbright scholarships for applicants who are married and have children; or educating women on their menstrual cycles so they understand when they are ovulating and can conceive.

The challenge is that, over the last 30 years, many countries have instituted pro-natalist policies – basing benefits on number of children, providing allowances for newborns, or offering child tax credits. The evidence suggests that these efforts haven’t worked. Sweden is a wonderful example, because even with soup-to-nuts support its fertility rate is 1.45 – significantly lower than the U.S. rate.

So, what’s the answer? Tell JD Vance and Elon Musk that $5,000 will do nothing. But also tell them that producing our own babies is not the only alternative. Increasing immigration is a direct way to raise the worker-to-retiree ratio and improve the finances of Social Security and Medicare. Sensitivity analysis by the Social Security actuaries shows that increasing net immigration by 200,000 per year would reduce the 75-year actuarial deficit, which is currently 3.5 percent of taxable payrolls, by roughly 0.2 percent of payrolls. That is, an increase in immigration can offset much of the cost pressure created by low fertility rates.