Medicare’s Finances and the Aduhelm Saga

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

The program is vulnerable to expensive new drugs.

It’s always worth taking a look at the finances of Medicare, given its contribution to the health and well-being of older Americans and its dependence on the payroll tax – the key source of revenue for Social Security. The topic is much more exciting – and frightening – in the wake of Aduhelm – a drug developed by Biogen to treat early-stage Alzheimer’s disease with an original ask price of $56,000 per patient per year.

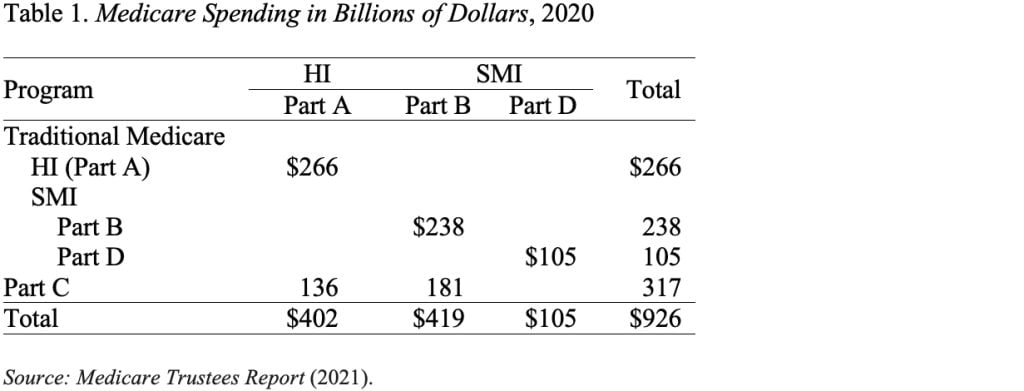

Traditional Medicare is composed of two programs (see Table 1). The first – Part A, Hospital Insurance (HI) – covers inpatient hospital services, skilled nursing facilities, home health care, and hospice care. The second – Supplementary Medical Insurance (SMI) – consists of two separate accounts: Part B, which covers physician and outpatient hospital services; and Part D, which covers prescription drugs. Medicare also includes Part C (the Medicare Advantage plan option), which makes payments to private plans that provide both Part A and Part B services.

Each Medicare program has its own trust fund and its own source of revenues. Part A (HI) is paid for primarily by a 2.9-percent payroll tax, shared equally by employers and employees. In addition, high-income workers pay a 0.9-percent tax on their earnings above a threshold of $200,000 for singles and $250,000 for married couples. The HI trust fund also receives a portion of federal income taxes that Social Security recipients pay on their benefits. SMI is financed by a combination of general revenues – about 75 percent – and participant premiums – about 25 percent.

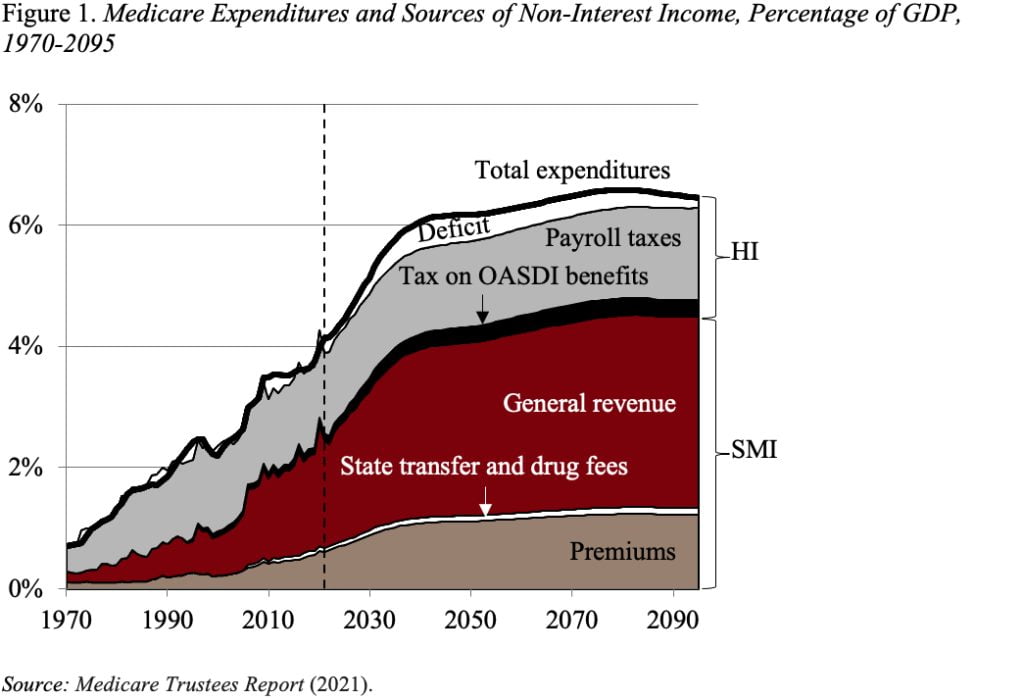

Figure 1 shows total Medicare spending and its sources of income. SMI is adequately financed for the indefinite future because the law provides for general revenues and participant premiums to meet the next year’s expected costs. Of course, an increasing claim on general revenues puts pressure on the federal budget and rising premiums place a growing burden on beneficiaries. In terms of HI, the small trust fund is projected to be exhausted in 2026, and revenues are not sufficient to cover costs, yielding a long-term deficit shown at the top of the figure.

In addition to projecting the program’s finances under current law, the actuaries also prepare an alternative scenario. This scenario limits the extent to which Medicare payments to hospitals and physicians fall below those made by private insurers. The concern is that prices can only be reduced so far before jeopardizing beneficiaries’ access to mainstream medical care. Under these alternative assumptions, spending as a share of GDP would be about 2 percentage points higher, requiring more general revenues and higher beneficiary premiums and roughly doubling the HI deficit.

The alternative projections, however, do not address the potential impact of much higher drug prices. This issue became particularly salient with Biogen’s introduction of Aduhelm to treat early-stage Alzheimer’s. Since Aduhelm is administered intravenously by physicians, it would be covered under Medicare Part B.

Two aspects of the Aduhelm issue are fascinating. On the one hand, the efficacy of Aduhelm is unproven; patients face serious risks; and the drug’s FDA approval was extremely controversial, so Medicare officials faced a real dilemma. On the other hand, what would have been the implications – in an environment where Medicare does not have the ability to negotiate prices – if clinical trials had clearly demonstrated that the drug could slow cognitive decline and Biogen had kept the price at $56,000 per year?

In the case of Aduhelm, Medicare officials issued a draft decision in January to limit coverage to those in clinical trials. The basis for their decision was concerns that the benefits of the drug did not outweigh the safety risks. Price played no role. The final decision is expected by April.

More next week!!