Minority Retirees: More Healthcare Access

The pandemic has dramatized the grim consequences of Black and Latino Americans having less access to healthcare than whites: disproportionately high death rates from COVID-19.

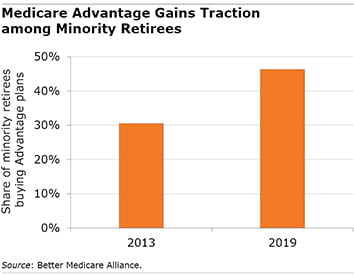

But there has been some progress toward racial equity in an unlikely place: Medicare Advantage plans sold by insurance companies. Enrollment in the plans has increased unabated for years, and minority enrollment more than doubled between 2013 and 2019.

But there has been some progress toward racial equity in an unlikely place: Medicare Advantage plans sold by insurance companies. Enrollment in the plans has increased unabated for years, and minority enrollment more than doubled between 2013 and 2019.

During that time, Advantage plans increased from about a third of the various Medicare options purchased by Black, Latino, Asian and other minority retirees to nearly half, according to the non-profit Better Medicare Alliance.

Dr. Elena Rios, president of the National Hispanic Medical Association, and Martin Hamlette, executive director of the National Medical Association representing Black physicians, said Advantage plans provide retirees with access to preventive services like mammograms and cholesterol checks that keep them healthy.

Advantage plans are “a needed tool in the work of building a more just health care system,” they wrote in a recent Health Affairs article.

The appeal is upfront affordability. The monthly premiums are significantly lower than Medigap premiums, and many Advantage plans charge no premium. They frequently include prescription drug coverage, eliminating the need to pay for a separate Part D drug plan.

The reason Advantage plans are especially popular with minorities is that they tend to have lower incomes than whites and less room in their monthly budgets for medical care. Three out of four minority retirees in Advantage plans have incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty level, compared with half of the whites in the plans.

Like all insurance, however, Advantage policies are a mixed bag. Medicare beneficiaries in poor health may face higher costs down the road if they experience a major medical crisis. In one study, the sickest retirees with Advantage plans had more risk of inordinately large annual out-of-pocket expenses for copayments and deductibles than retirees with Medigap plans.

Advantage plans are standalone insurance policies and distinct from Medigap plans, which are supplements to the basic Medicare coverage. Advantage plans control their prices by requiring patients to use a network of doctors and hospitals that limit where patients can go for care.

But the evidence of improvements in health care access can be found in an independent study by RAND, commissioned by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. While white retirees continue to have better access to medical care, Black, Latino and Asian retirees who purchased Advantage plans have seen improvements over the past decade in key clinical services, including flu vaccinations, eye exams for diabetes patients, and the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and heart disease with medications.

Avoidable hospitalizations and hospital readmissions were also much lower for Advantage customers than for retirees with original Medicare and Part D, according to an Avalere study funded by the Better Medicare Alliance, which advocates for the federal Advantage program on behalf of retirees, medical professionals, and insurers. (Insurers also fund the alliance.) And many plans wrap various services into the policies, and amount to additional coverage for everything from vision care to Meals on Wheels deliveries.

COVID-19 has exposed the racial inequities in our healthcare system. Perhaps the lessons of the pandemic will translate to even more progress for retirees.

Squared Away writer Kim Blanton invites you to follow us on Twitter @SquaredAwayBC. To stay current on our blog, please join our free email list. You’ll receive just one email each week – with links to the two new posts for that week – when you sign up here. This blog is supported by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Comments are closed.

Predatory practices….