Dicey Retirement: The Long Ride Down

No one really needs confirmation of how tough the Great Recession was. But the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College has quantified the decline – and it’s brutal.

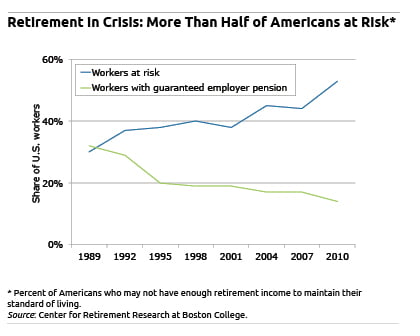

Investment losses and falling home prices placed 53 percent of U.S. households in danger of a decline in their standard of living once they quit working and retire, reports the Center, which funds this blog. That’s up sharply from 45 percent in 2004, prior to the financial boom, which created a strong – albeit fleeting – increase in Americans’ wealth.

The longer-term erosion in Americans’ retirement prospects is even more troubling and reflects deeper issues. The Great Recession just hammered the point home.

In 1989, just under one-third of Americans faced such dicey retirement prospects. The steady erosion since then coincides with the near-extinction of traditional employer pensions that guaranteed retirees a fixed level of income. It turns out that the DIY system that replaced them, a system reliant on Americans’ ability to save in their 401(k)s, is not working.

Older baby boomer households with 401(k)s have just $120,000 saved for retirement, according to the Center. That’s not even enough to pay estimated medical costs not covered by Medicare. Retirement savings for all older boomer households is a paltry $42,000 – that means a lot of people have no savings.

Economic forces are making saving for retirement difficult.

Former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich in his 2011 book, “Aftershock: The Next Economy and America’s Future,” notes that it’s difficult to save money when U.S. wages have stagnated due to foreign competition, productivity gains, economic booms and busts and other factors out of our control. Further, he blames stagnant wages for the run-up in debt over the past 15 years – debt is the opposite of saving.

To be sure, the increase in the Center’s National Retirement Risk Index (NRRI) to 53 percent is based on 2010 data from the Federal Reserve’s triennial Survey of Consumer Finances. Plunging home values nationwide accounted for half of the increase in the share of all U.S. households at risk. But the 2010 data do not reflect recent, slight improvements in house prices and the 2012 stock market rise.

From 2007 to 2010, the increase in the NRRI was mildest for the low-income people who can count on Social Security for most or all of their retirement income, according to a research brief detailing the NRRI. Retirement prospects for middle- and high-income Americans worsened more, due to 24-percent drops in both housing prices and the stock market between 2007 and 2010.

The assumptions behind this dire outlook are conservative, too: More than half of Americans are expected to be at risk, “even if they work to age 65,” the Center said.

The NRRI is calculated using estimates of what are known as “replacement rates” for U.S. households. A replacement rate is the ratio of a household’s retirement income to the income earned during the household’s working years. The index is the percentage of all households whose projected retirement income falls more than 10 percent short. [And, yes, this index already takes into account the fact that retirees no longer need to save or pay payroll taxes.]