New Alzheimer’s Drug Shows Some Promise, but Has Big Price Tag

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

How to alleviate ravages of the disease without bankrupting individuals or Medicare program?

The Food and Drug Administration recently granted fast-track approval to a new Alzheimer’s drug designed to slow the rate of cognitive decline for individuals in the early stages of the disease. The drug, which will be sold under the brand name Leqembi, was developed jointly by Eisai and Biogen – the same two companies that developed its controversial predecessor Aduhelm – and will be priced at $26,500 per year.

The question is whether Medicare will follow the same path with Leqembi as it did with Aduhelm. Leqembi has received a slightly warmer reception from the medical community than Aduhelm, because a large trial showed it actually slowed the progression of Alzheimer’s (a clinical benefit), as opposed to simply removing plaque from the brain (a surrogate end point). But, as in the case of its predecessor, Leqembi involves side effects, such as swelling and bleeding in the brain, which means patients must receive periodic brain scans after starting treatment.

In the case of Aduhelm, concern over whether the benefits of the drug outweighed the risks led the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid to extend coverage only for individuals participating in randomized clinical trials. The ruling applies not just to Aduhelm, but to all Alzheimer’s drugs that target amyloid and have not received full FDA approval. Leqembi falls under the umbrella on both counts. Hence, in the short run, Medicare is unlikely to extend coverage, and private insurers tend to take their lead from Medicare.

In the longer run, Eisai and Biogen have now applied for FDA approval of Leqembi under the traditional pathway. With clearer assurance that Leqembi helps patients, Medicare could cover it for all eligible patients, perhaps imposing a requirement that the patient’s experience be tracked. Leqembi is now available on the market. But without Medicare or private insurance, only the wealthy will be able to afford the cost of $26,500 per year. They will have to balance the cost against slowing the progression of the disease by 3-5 months. Because the trial ran for 18 months, it’s too early to tell whether Leqembi has any long-term benefits.

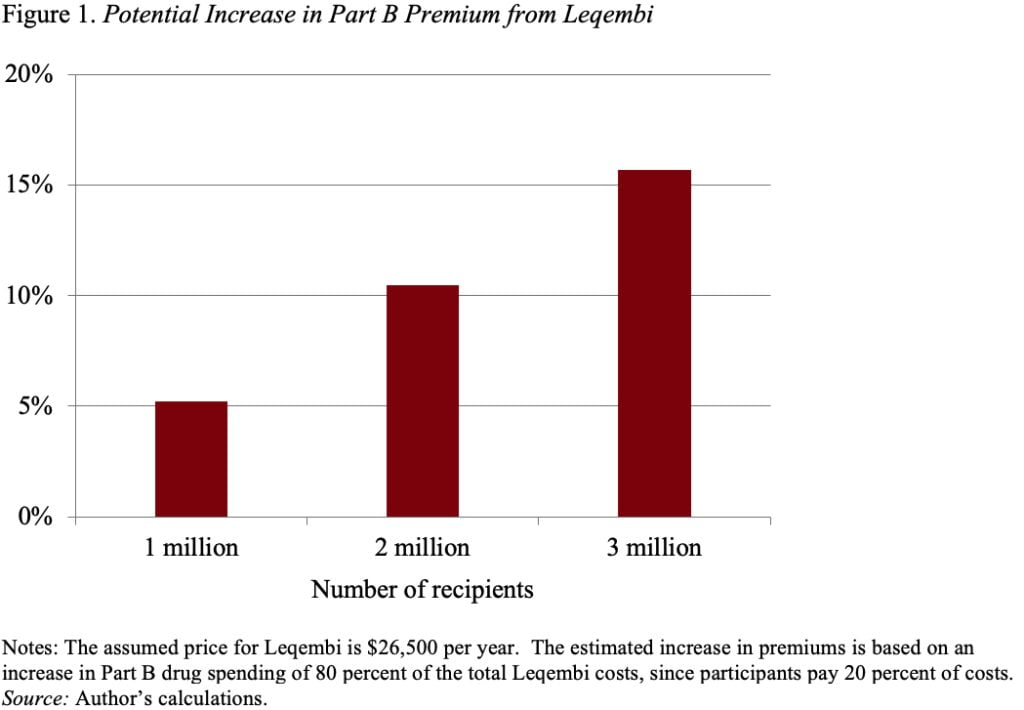

In the longer run, Medicare may well extend coverage in the wake of full FDA approval, and many more individuals will have access. At this point, the impact of Leqembi on Medicare finances becomes an important issue. At a price of $26,500, and assuming 1 million recipients, Medicare’s bill would be $21 billion (Medicare pays 80 percent and beneficiaries pay 20 percent in copayments). A $21-billion increase would require a 5-percent increase in Part B premiums. Those costs over time would rise as more and more people are stricken with Alzheimer’s and become eligible (see Figure 1). (It’s worth noting that, under a provision in the recent Inflation Reduction Act, Leqembi could be required to lower its price for Medicare recipients starting in 2028, but the cost would still be substantial.)

Leqembi patients would also pay high out-of-pocket costs both for the drug and for related medical services, such as regular MRI scans. So, at a minimum, beneficiaries facing the current Leqembi price would pay $5,300 for a one-year supply of the drug. Traditional beneficiaries without a Medigap policy would face the cost directly; those with a Medigap policy would see their premiums rise; and those in Medicare Advantage plans would also be responsible for cost-sharing until they reached their annual out-of-pocket maximum. All these increased expenditures would be devastating to the typical Medicare beneficiary with an income of about $30,000. And, as noted, Leqembi is not a cure, so patients would likely incur these costs for multiple years.

Clearly, the goal of society is to alleviate the ravages of a dreadful disease, but we need to think about how to pay for drugs without undermining the financial security of the nation’s retirees.