People Aren’t Giving Up Their Day Jobs for Uber

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

New study provides unique window on gig economy.

Talking about the gig economy is clearly cool. The problem is that commentators use a wide range of definitions, and estimates vary widely not only on the prevalence of gig activity but also the trend. Into this morass comes work from the team at the JP Morgan Chase Institute, which presents a clear picture of what’s going on using well-defined concepts and a fabulous data set.

The data consist of transactions by 39 million de-identified account holders who use a Chase checking account as their primary financial tool. The study includes 128 online platforms that connect suppliers with customers, mediate payments, and allow participants to enter and leave when they want. The scope of this analysis represents a significant increase from the 42 platforms included in a 2016 study, although the original platforms continue to account for the bulk of the activity.

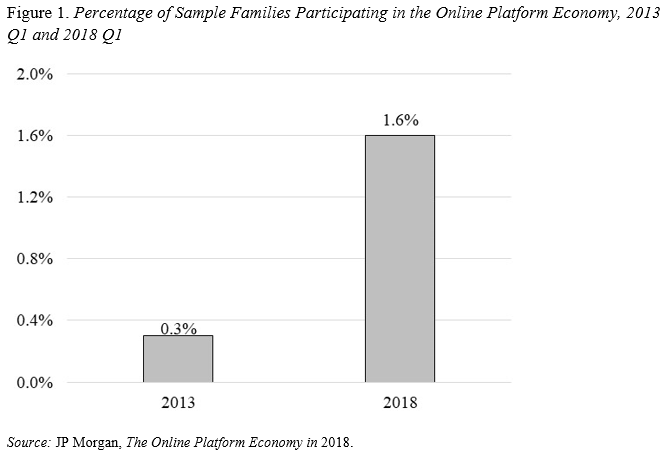

The results show that, from October 2012 to March 2018, 38 million payments from the Online Platform Economy went to 2.3 million Chase checking accounts. These accounts amounted to about 6 percent of the 39 million account holders in the sample. To get some idea of the growth in platform transactions, the fraction of the sample who earned platform income in the first quarter increased from 0.3 percent in the first quarter of 2013 to 1.6 percent in the first quarter of 2018 (see Figure 1). Generalizing these fractions to the 126 million U.S. households suggests that 2 million households per month, or 5.5 million households over the year, participated in the Online Platform Economy.

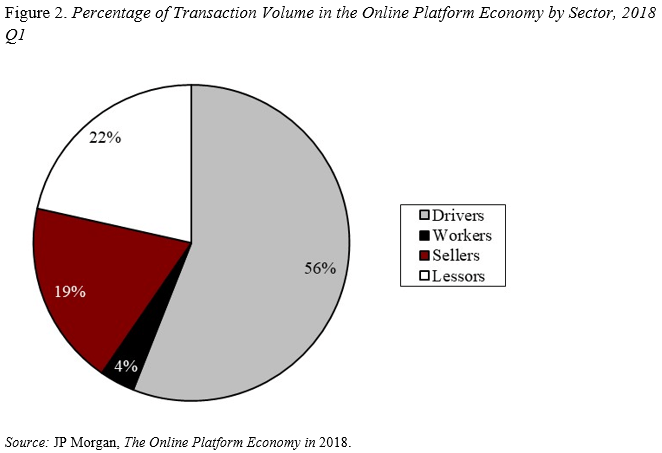

The authors disaggregate the Online Platform Economy into four sectors:

- Drivers, who transport people or goods;

- Workers, who offer services such as home repair, dog walking, etc.

- Sellers, who offer crafts, used books, etc.

- Lessors, who rent out homes, parking spaces, etc.

As Figure 2 shows, drivers account for the bulk of platform participants in the first quarter of 2018. While the percentage participating as drivers has increased in the last five years, average earnings from the transportation sector declined by more than 50 percent. Whether the decline reflects a fall in wages, a decline in hours, or both, driving is less and less likely to replace a full-time job.

The overall conclusion emerging from the report is that people are not quitting their day jobs to participate in the Online Platform Economy. Most families continue to rely on traditional sources of income; only a small percentage receive platform earnings. The majority of those who do participate engage on only an occasional basis (less than three months) and generally earn less than $1,000 a month. On average, platform earnings account for only about 20 percent of income for those who have participated at any point in a year.

The JP Morgan Chase Institute analysis, of course, is only one window on the gig economy. Its sample consists of families rather than individuals and overrepresents younger families, male-headed families, and families in the West. Nevertheless, the unit of observation and the demographic differences with the U.S. population are consistent over time, so these factors are not driving the trends.

Until somebody convinces me otherwise, I’m staying with the conclusion that we are not all about to quit our day jobs and become Uber drivers.