Nursing Homes Can’t Meet the Care Needs of an Aging Population

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Where are we going to get the workers to care for us? How are we going to pay them?

In my view, long-term care is one of the major challenges facing an aging society. Care can take the form of a nursing home, formal care provided in the community or home, or informal care provided by family or friends. KFF recently released a really nice summary of the state of play on the nursing home front in the process of describing a proposed rule that would create new staffing requirements.

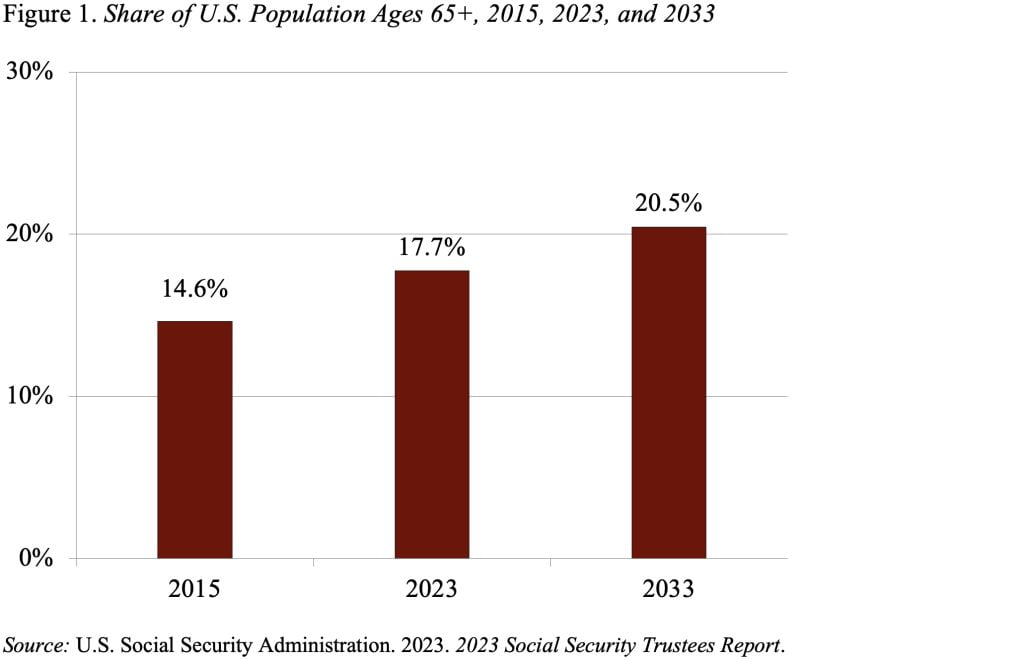

Nobody really wants to go to a nursing home, and the long-standing staffing issues combined with the death of 170,000 residents during COVID have contributed to a decline between 2015 and 2023 in the number of nursing homes and nursing home residents. This decline has occurred despite a significant increase in potential customers as the population ages (see Figure 1).

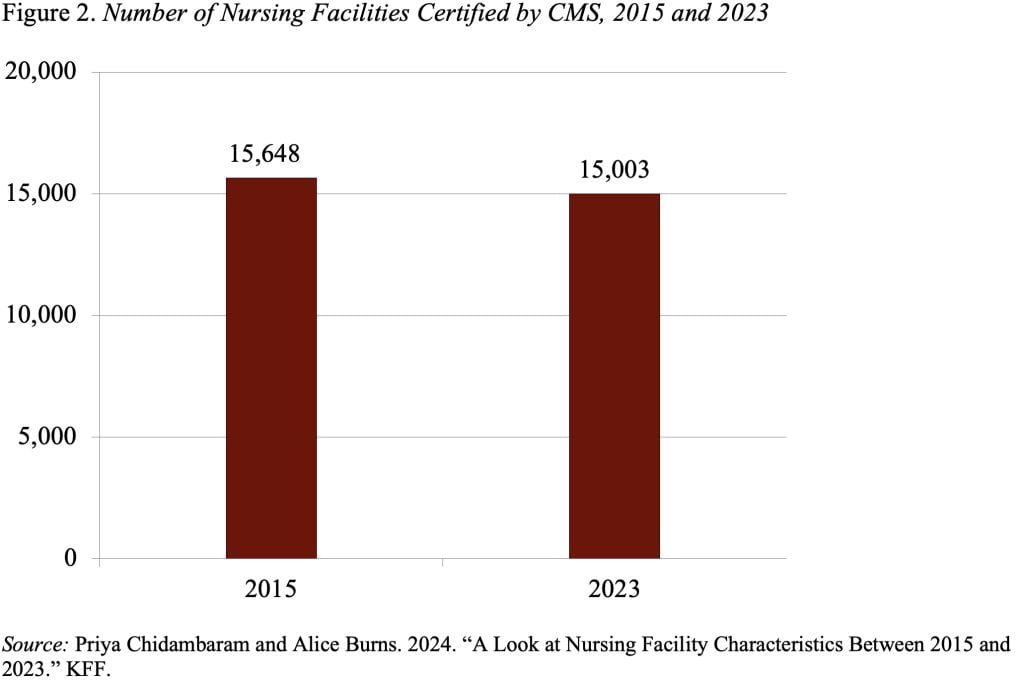

Let’s start with the simplest measure – the number of nursing homes. To be eligible for reimbursement under Medicare or Medicaid, nursing homes have to be certified by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The number of certified nursing facilities declined 4 percent between 2015 and 2023 (see Figure 2).

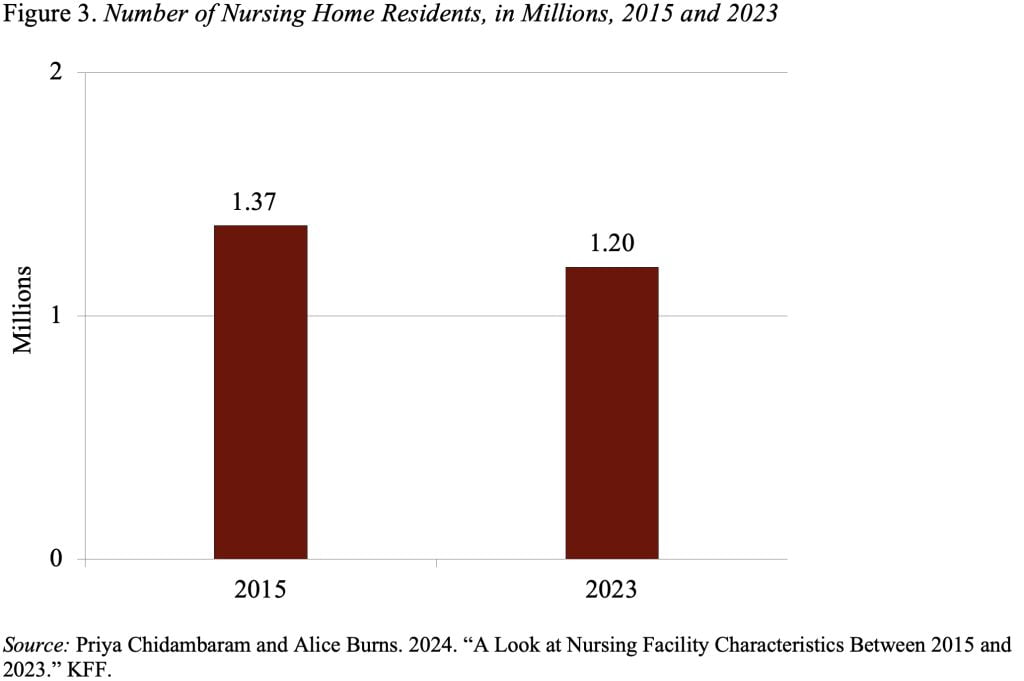

Over the same period, the number of nursing home residents declined by 12 percent, as people increasingly opted for care in their community or home (see Figure 3). The COVID deaths exacerbated the decline.

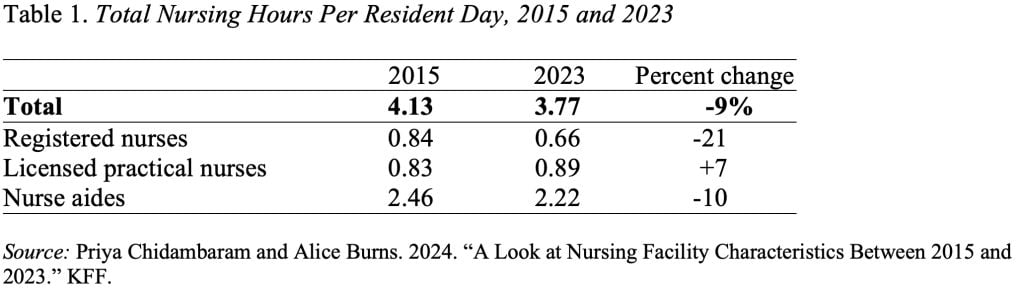

And the remaining residents received fewer hours of care. The decline was driven by a 21-percent drop in the care provided by registered nurses (RNs), who are responsible for assessing the needs of residents and delivering overall care. The hours of care provided by licensed practical nurses (LPNs), who are responsible for making sure each resident’s plan of care is carried out, actually increased slightly. The third part of the team consists of nurse aides, who work under the licensed nurses and assist with activities of daily living, such as eating, bathing, dressing, walking, and using the bathroom. The hours provided by nurse aides, who are the people who spend the most time with the residents, declined by 10 percent (see Table 1).

Interestingly, the Biden administration’s new proposed staffing rule for registered nurses of 0.55 hour per resident day is slightly lower than the average provided in 2023. The proposed minimum of 2.45 hours for nurse aides is slightly higher than the average currently provided. The rule includes no proposed minimum for licensed practical nurses.

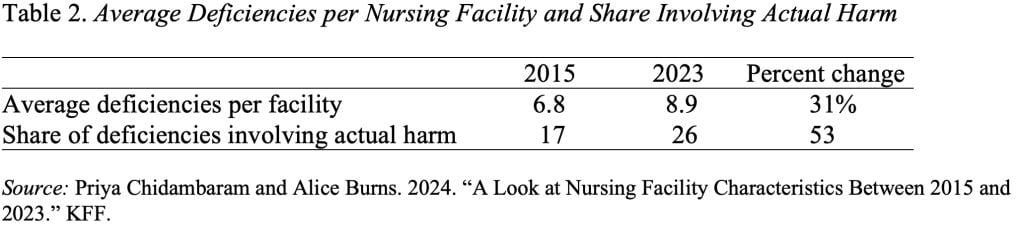

The average, however, could hide a lot of variation among nursing facilities, and the data on the average number of deficiencies and the share of facilities with serious deficiencies suggest that many facilities are providing significantly fewer hours than the new proposed minimums (see Table 2).

The proposed new rule for minimum hours recognizes the staffing problem at nursing homes, but also raises the larger questions of whether we have sufficient workers to care for an aging population and how we are going to pay for all that care.