Our Stubborn State of Financial Illiteracy

The U.S. retirement system is built on people having a working knowledge of finance. Yet financial literacy among a big chunk of Americans ranges from unimpressive to abysmal.

This revelation was again confirmed in a survey that recently debuted by financial literacy guru Annamaria Lusardi, head of the Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center at George Washington University. In a 2011 survey, Lusardi had found that too many Americans were unable to answer three very simple financial questions.

This new survey is more ambitious, though the results are no more promising. It asks 28 questions in eight areas: earning money, budgeting, saving, investing, borrowing, insuring, understanding risk, and information sources. In the nationally representative survey, about one in four people got no more than seven answers (25%) correct.

One telling finding is that the highest scores were for knowledge about borrowing, with nearly two out of three answering these questions correctly. I suspect this knowledge has been gained from experience – experience with high-interest credit card bills and onerous student loan payments, as well as mortgages.

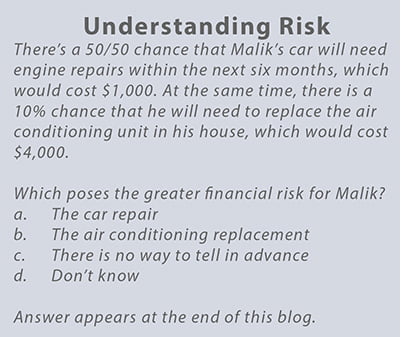

For every other financial topic surveyed, about half or less answered the questions correctly. Questions about risk, which is at the heart of many financial decisions, fared worst – only 39 percent answered these correctly.

For every other financial topic surveyed, about half or less answered the questions correctly. Questions about risk, which is at the heart of many financial decisions, fared worst – only 39 percent answered these correctly.

An important connection is made in the report regarding 18- to 44-year olds, who answered only 41 percent of the questions correctly (versus 55 percent for people over 45). Younger adults also answered “I do not know” most often.

When it comes to retirement, those who would gain more from financial knowledge are the least knowledgeable. Saving that starts in early adulthood can go a long way toward achieving retirement security, thanks to compound investment returns over the many years remaining prior to leaving the work force. It’s unfortunate that those who could benefit from compounding often don’t comprehend its effect.

No surprise that financial knowledge increases as household incomes and education levels rise.

Nevertheless, “It is concerning that so many Americans appear to lack knowledge that enables sound financial decision-making,” the survey concludes. To read the entire survey, click here.

It’s much easier to measure financial literacy – or the lack of it – than to figure out how to fix it, though Lusardi would start with teaching financial literacy in high school.

What is also clear is that everyone bears some responsibility for the dismal state of financial literacy and to do what we can to reduce the harm that financial illiteracy creates.

Answer to risk question: The car repair. While it’s true that it is impossible to predict the future, one can put a dollar value on the financial risk that each breakdown – the car and the air conditioner – might occur. Here’s how to do that: a $1,000 car repair with a 50 percent chance of occurring is a $500 risk ($1,000 x .50). A $4,000 air conditioner replacement with a 10 percent chance of occurring is a $400 risk ($4,000 x .10).

Squared Away writer Kim Blanton invites you to follow us on Twitter @SquaredAwayBC. To stay current on our blog, please join our free email list. You’ll receive just one email each week – with links to the two new posts for that week – when you sign up here.

Comments are closed.

With respect to your example, it depends on how you define financial risk. While you have correctly calculated the expected value of the two risks, one could argue that that is not the risk itself. The risk associated with the car repair, if it is to occur, is $1,000; the risk associated with the air conditioner repair, if it is to occur, is $4,000. Now it’s true that the probability of occurrence is much lower for the air conditioner, but does that change the financial risk?

This article is DREADFUL — par for the course for the whole academic community concerned with the field of finance. The ROOT of the problem is not the people, but the community of finance PROFESSORS. They teach financial DECEPTION.

The sample question illustrates. Financial academics teach misuse of the fear-word “risk” to include NO consideration of dollars, instead mean only the technical uncertainty measure of return-rate standard deviation — for the individual year.

This deception serves the interests of the fees-extracting financial community instead of the public. It diverts people’s focus and fear to the individual year, where they cannot see the long-term cost of annual financial-community fees.

Want another example? Try “Expected return” for a return that is NOT EXPECTED.

For over a decade, Fi360 and the AICPA have applied finance professors’ deceptions to teach “fiduciaries” use of that deception as the basis for guiding people to expect to meet long-term goals with investments that are expected to fall short.

Until the community of finance professors basing their teachings on these deceptions is purged, any “fiduciary standard” applying academic financial teachings will only make things worse.

An interesting risk question and a good analysis, as far as it goes.

But what about cash flow problems? Many people — who might be able to scrape together $1,000 for the repair — would have serious trouble raising $4,000 for air conditioning.

Which is more serious, loss of car or loss of AC? Many people are very dependent on their cars. (Some might borrow, rent, bus, taxi, car pool, etc.) Many people are only mildly discomforted w/o AC. (What is the temperature, humidity, wind, etc.)

Such an important issue

Why do so many resist classes and/ consultations with professionals?

They hire professionals to take care of their hair, fix their cars etc. Why not consult professionals about their money?

Fiduciary standard! Based on what underlying principles? Should the CFPs be cutting hair or repairing cars, etc.? No discredit to any profession, but great advice by what standard?

What about valuation of the request? If the car is of minimal use and public transportation or a car pool is available, not so risky. But if the house is in Florida and it’s in the summer – you’re going to get the AC fixed somehow.

Annamaria knows better. The answer is not A. The biggest risk is the one that has the greatest effect on utility. To answer the question, you have to know how much more unhappy you will be about a $4,000 loss than about a $1,000 loss. If you are risk averse, the AC may be the bigger risk

The answer to this question may be how an academic financial nerd would look at it, but it’s not real life. Malik would be well-advised to put aside $5,000 to cover both the car and AC. Sooner or later, both are going to go and he will have to come up with a heck of a lot more money than $1,000.

Putting aside a good amount of money to cover emergencies — the old 6-months salary rule — is the financially responsible way to ensure the ability to handle unexpected expenses without going into debt. That’s the rule that should be taught, and the rule we have lived by and taught to our children. The state of financial education in this country is indeed abysmal. But teaching airy-fairy concepts about risk will not help Malik — and thousands like him — manage his money on a practical level.

There are many problems with this area of research, some of which the previous comments have touched on. Most importantly, the economics community has known for years that people often do not think in terms of expected outcomes, and I’m not convinced that we should. The above example question shows just how ridiculous and misleading this line of research can be. Answers will vary due to (a) individual framing, (b) relative utility weights of A/C versus vehicle access, (c) perceived credit availability or ability to save a large sum, (d) initial asset position, etc. The list goes on. Thus, that the paper finds 41% of respondents answered “correctly” means nothing. And with multiple choice answers, they cannot determine how or why people chose that answer, or any other answer. Rather than learning something from this research question, the information gain is at most zero, and more likely negative (mis-information). I sincerely hope this is not the best we as a profession can do.

Interesting comment. This topic reminds me of the new PBS series “Victorian Slum House” where people try to live and work like the poor in East London. Meager earnings reduce them to a grim basic choice of which to pay: Rent, food or clothing? Slum dwellers soon realize without shelter the risk of sickness increases, making it nearly impossible to earn anything. Even today, the biggest financial risk most face in their working years is losing the ability to work and earn income. I wonder if disability insurance is even addressed in the survey?

Love the comments because they say everything is relative. Guess what? It is! Every life is different. Financial literacy is understanding you need health, values, education, a good work ethic, and time. That will carry you through the bad times. If you want more, find three good CFP fiduciaries and give each some money and leave it alone while you follow your values. In time, compounding will reward you. Was a ditch digger all my life. Those three CFPs now say I’ll never out live our money. Have a crystal ball? I held a 5,000,000 deutschmark from the 1920s – worthless shortly after issue. Financial literacy?? Is this hard to understand?