Paid Sick Time Wins on Ballots

In last Tuesday’s election, voters in Massachusetts and three cities – Oakland, California, and Montclair and Trenton, New Jersey – approved paid sick time initiatives that benefit working mothers in particular.

These election results come on the heels of a slew of similar initiatives approved in the past year covering all or certain groups of workers in California and in San Diego, Washington, DC; Eugene, Oregon; several New Jersey municipalities; and the Tacoma suburb of SeaTac, according to an inventory of sick time laws compiled by the advocacy group, A Better Balance.

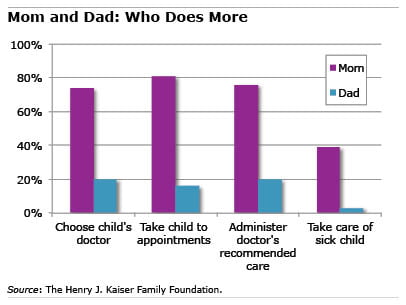

Mandated paid sick time for employees is growing in popularity but is still unavailable to significant numbers of working mothers, who, the data show, are more often responsible for children’s health than fathers. This issue is one more thing that – like lower pay – can disadvantage single women struggling to secure their personal finances today or save for retirement in the future, especially low-income women.

Research by Usha Ranji, associate director of women’s health policy for the health care non-profit organization, the Kaiser Family Foundation, found that 39 percent of working moms are forced to miss work when a child is sick, because they don’t have back-up child care; of them, 60 percent do not get paid for that time – a decade ago, fewer than half of this group were in this position.

Low-income mothers, Ranji adds, “are the ones who are more likely to stay at home when their kids are sick, and they’re less likely to get paid. I think that’s really important.”

Low-income mothers, Ranji adds, “are the ones who are more likely to stay at home when their kids are sick, and they’re less likely to get paid. I think that’s really important.”

The absence of paid sick time also affects husbands and fathers. But according to a survey last year by the Kaiser Family Foundation, wives are far more likely to stay home from work to care for a sick child, and 43 percent of all working mothers are not offered paid sick days by their employers.

The voter-approved initiatives mark an improvement, but many working mothers still face the dilemma: stay home or earn money.

Comments are closed.

This is all well and good and it initially benefits the incumbents. But longer-term, it tends to force exactly these women out of the workforce. I once worked as a consultant in a large European company and their central purchasing department (that handled all the larger contracts) had a staff of about 30. The manager once told me privately, when I saw he was hiring men most of the time, that although the work was typically a women’s domain (a lot of translating into foreign languages and a lot of typing), “I have a staff of about 30 – currently I have 7 women out on maternity leave. If they all came back I wouldn’t know what to do. But I don’t know if they choose to come back nor can they give me a clear indication or they’ll lose their status. I can certainly not afford to hire any more women under the age of 50.” While this is not exactly the same as sick leave in general, if you frame it so that mothers are likely to take more paid time off than other staff, the conclusion is obvious: they are pricier for the same work than others and thus will get hired less and fired more. I’m not sure how anyone can call that progress.