Payroll-Deduction IRAs Are Becoming Cheaper and Easier

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

But that doesn’t mean we should change the contribution limits.

The technology associated with payroll-deduction IRAs is making it easier and cheaper for employers to enroll their employees in these accounts. That’s wonderful. At any given time, roughly half of private sector workers – primarily those at small companies and the relatively lower paid – do not have an employer plan at work, and being enrolled in an IRA dramatically increases their chances of being prepared for retirement. The new state auto-IRA programs, which are currently up and running in California, Illinois, and Oregon, are designed to address this problem.

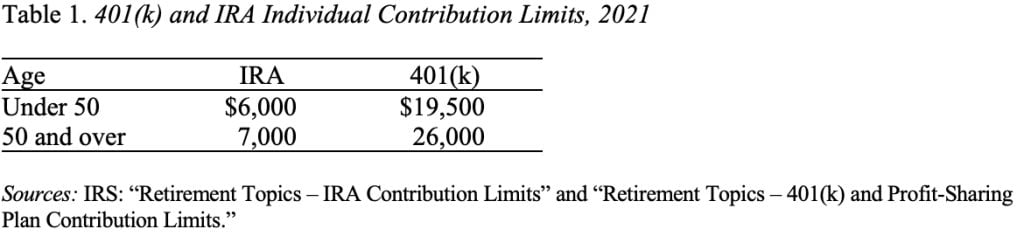

Enthusiasts of the new technology, however, see a market for payroll-deduction IRAs beyond the new state programs. They argue that the growing number of relatively high-paid workers employed on a contract basis could benefit from easy access to an IRA. And, in this context, they argue that the IRA contribution limits should be raised to make them comparable with 401(k) plans. That is, the employee contribution to IRAs should be raised from $6,000 to $19,500 for those under 50 and from $7,000 to 26,000 for those 50 and over (see Table 1).

At first, that seems like a perfectly reasonable thing to do. It would simplify the system and allow higher-paid workers without a plan to save more.

But, in fact, raising the IRA limits risks crowding-out 401(k)s. Such a step would undermine our existing retirement system because 401(k) plans are better for employees than IRAs. IRAs lack important nondiscrimination standards that limit the ability to skew benefits in favor of owners and executives; and they also lack ERISA’s protections for plan participants from imprudent investments, excessive fees, and the like. In fact, 401(k) fees have been coming down – due in part to the fee disclosure rules, which require 401(k) plans to disclose their fees in an easily understandable format. Financial services firms handling IRAs face no such requirement.

Currently, employers have no incentive to drop or refrain from adopting a 401(k) in favor of a payroll-deduction IRA, because 401(k)s permit significantly more generous tax-favored contributions than IRAs and offer the potential for employer contributions. Increasing IRA contribution limits would alter that calculation.

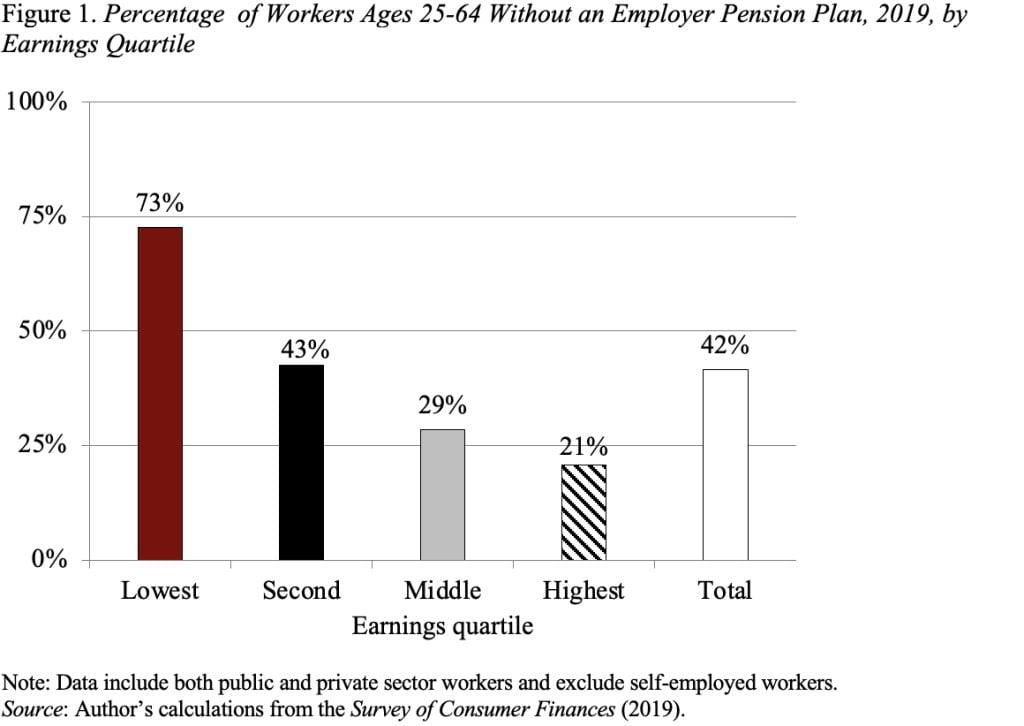

Furthermore, the current IRA contribution limits are unlikely to serve as a constraint on most workers without a retirement plan. These workers tend to work for smaller firms and receive lower wages. As shown in Figure 1, only 21 percent of workers ages 25-64 with earnings in the top quartile of the earnings distribution did not have an employer plan compared to 73 percent of those with earnings in the lowest quartile.

In 2020, median earnings for a worker ages 25-64 (excluding the self employed) were about $55,000. The current IRA contribution limits would allow all the uncovered in the bottom two quartiles of the earnings distribution to contribute more than 10 percent of their earnings to a retirement plan – a fairly ambitious goal for the lower paid. The relatively small percentage of uncovered workers in the upper quartiles might be somewhat constrained, but that risk does not merit undermining our entire retirement income system.