People Are Working Longer, But Are They Claiming Social Security Later?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Two different measures tell a similar story.

Working longer has been generally accepted as good advice for a secure retirement. It directly increases current income; it allows people to contribute more to their 401(k)s; it shortens the period of retirement; and, importantly, delaying claiming of Social Security results in a much higher monthly benefit. The good news is that people have responded; the long-term trend toward earlier retirement came to a halt in the mid-1980s, labor force participation rates at older ages began to increase in the mid-1990s, and since then the average retirement age has increased by three years. The question is the extent to which working longer has translated into delayed claiming of Social Security benefits.

Some information can be gleaned from the claims data published annually by the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA). These data show, for all workers claiming benefits in a given year, the percentage who are ages 62, 63, 64, etc., which is informative for any given year. But when the size of the group turning 62 is increasing substantially each year, the claims data underestimate the trend toward later claiming. That is, the data will show age-62 claimants making up a larger portion of total new claimants in a given year even if a smaller percentage of those age 62 claim immediately. To accurately follow claiming behavior over time, one must look at cohort data. Such data show, of the potential claimants turning 62 in a given year, the percentage who claim as soon as possible. In a recent study, we used both sources of data to look at long-term trends in claiming.

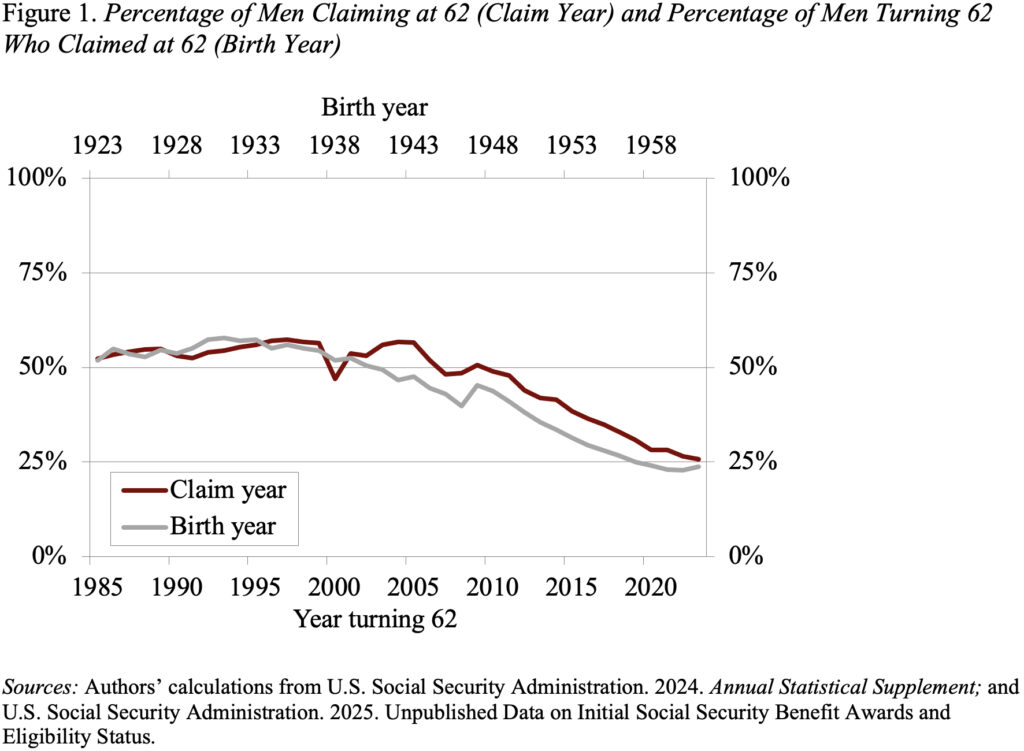

One way to glean whether people are claiming later as well as working longer is to look at the percentage of workers who claim as soon as benefits are available at age 62. Figure 1 shows the percentage of men claiming at age 62 under the two approaches described above. The claim-year line shows the percentage of all those claiming in a given year who are 62; the birth-year line shows the percentage of those born in a given year who claim at 62. The two approaches provide very similar results until 1997; afterward, the two series start to diverge. The birth-year data reflect the uptick in labor force activity beginning in the mid-1990s and show a much larger decline over the last three decades than the claim-age data.

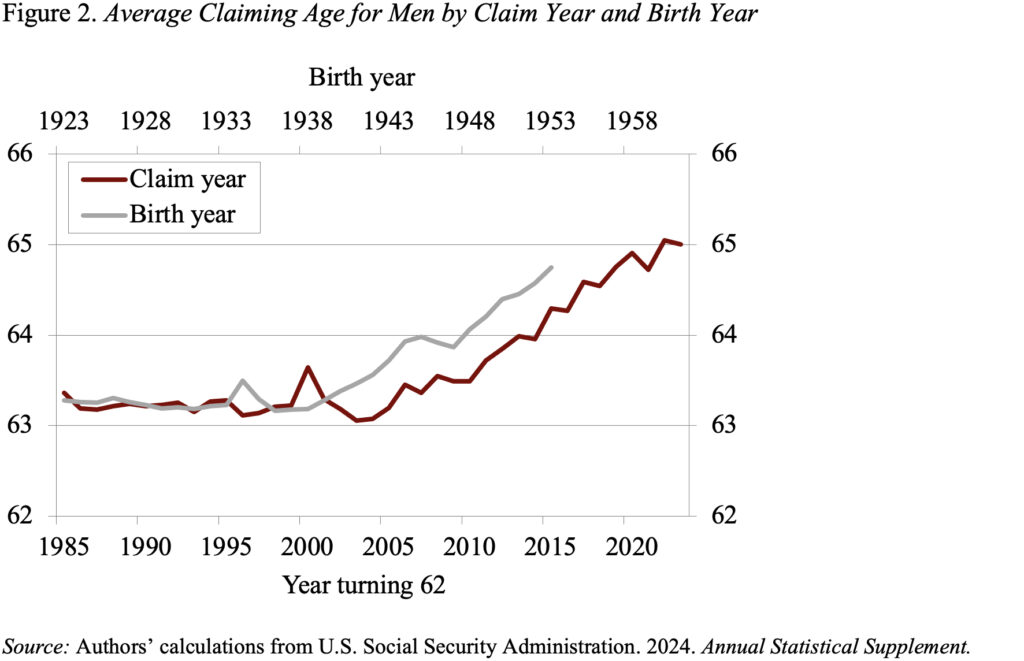

Figure 2 presents the trend from 1985-2023 in the average claiming age for men on a claim-year and birth-year basis (those cohorts turning 62 after 2015 do not reach age 70 by 2023). As one would expect, the increase is larger using the birth-year data, but both support the contention that the delay in retirement has been accompanied by a delay in claiming. The delay in claiming, however – even using the birth-year data – is only about two years – slightly less than the three-year increase in the average retirement age.

The bottom line is that “yes” people are claiming later, but the increase in claiming age is slightly less than what one would expect from the increase in work at older ages – and that finding holds regardless of whether the focus is people claiming in a given year or people born in a given year.