“Repeal and Replace” Seemingly Small Cap on Medicaid Isn’t Small

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Cuts will cascade just as Baby Boomers age into need for nursing home care.

According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the House version of “Repeal and Replace” would cut federal health care expenditures by $1.2 trillion over the decade 2017-2026, result in 24 million fewer Americans having medical insurance by 2026, and impose a cap on federal Medicaid expenditures that is estimated to reduce the annual growth rate by 0.7 percentage points. This restraint on Medicaid spending growth, which is less stringent than the cap in the Senate bill, might seem like small potatoes compared to the legislation’s other effects (which include a separate provision that eliminates enhanced federal support for the Medicaid expansion).

Federal Medicaid expenditures, under current law, are matching contributions: the federal government matches state Medicaid expenditures, for traditional beneficiaries, dollar-for-dollar in rich states and nearly three-to-one dollars in the poorest state. The House bill would tie federal matching expenditures to the rise in the consumer price index for medical services (CPI-M) since 2016, with the cap going into effect in 2020; the Senate bill would tie the cap to the slower growing CPI.

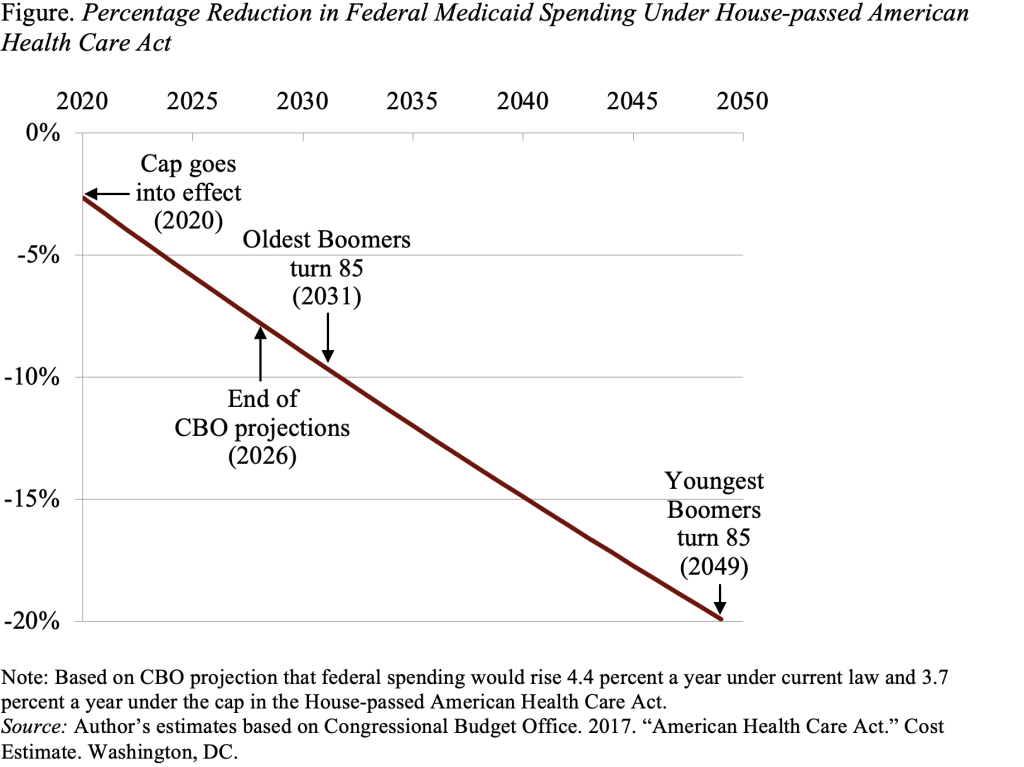

As indicated in the Figure, the House bill’s more generous cap is estimated to cut federal Medicaid expenditures by 7 percent in 2026, at the end of the CBO projection period. If this seemingly small constraint remains in place, the reduction in Medicaid sending from current law would amount to 10 percent in 2031, and 20 percent in 2049.

This cut in federal Medicaid expenditures would clearly affect the elderly. Nearly 20 percent of Medicaid expenditures currently go to the elderly, primarily for long-term care. Given the extremely high cost of nursing homes and other forms of long-term care, many middle-income and even some well-to-do elderly individuals exhaust their assets and rely on Medicaid to cover the cost of care. As a result, half of all expenditures for the long-term care of the elderly are currently provided by Medicaid.

Expenditures for the elderly should begin to rise sharply in 2031, when the oldest Boomers turn 85, and stabilize at a much higher level by the time the youngest Boomer turns 85, in 2049. The cap makes no accommodation for what is likely to be a dramatic rise in the “average” cost of an elderly beneficiary.

The states – especially states heavily dependent on federal Medicaid funds – cannot be expected to fill the gap by spending more. Medicaid already takes 20 percent of average state revenues. So the states would likely pay providers less and reduce enrollment and benefits. The long-term effect of a seemingly modest cap on federal Medicaid spending, combined with the predictable rise in long-term care costs for a rapidly expanding number of elderly Boomers, is likely to significantly diminish the well-being of seniors – as well as the disabled and low-income households who would all be competing for Medicaid’s diminishing resources.