Save Social Security from the Budgeteers!

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Social Security is not just a budget issue; it is the backbone of our retirement system.

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB), a bi-partisan group of budget experts committed to educating the public about fiscal issues, recently came out with “Nine Social Security Myths You Shouldn’t Believe.” I love the Social Security program, believe it is the backbone of our retirement system, and would like to see 75-year financial balance restored. That said, budget people scare me when looking at Social Security. They see the 75-year shortfall as a simple mismatch of revenues and expenditures, want the gap closed, and many – not all – don’t care very much how that is done. My view is that Social Security will be the major source of income for most of the population, so cutting benefits, as opposed to putting in more revenues, would be a serious mistake.

In that context, let me show you all nine myths (see below) and give you my reaction. Myths #2 and #3 exaggerate the size of the problem and treat the notion of having the rich pay more as unhelpful if it does not eliminate the whole shortfall. Myths #5, #6, and #7 are inside baseball; and, while the CRFB’s explanations are literally correct, they are not true in a broader sense. For example, regarding Myth #6, the important thing to know is that Social Security cannot spend money it does not have. It is a diversion to argue in some narrowly defined way it can run a deficit. While the CRFB’s explanation for Myth #8 is certainly correct, the statement itself is a red herring and not worthy of “myth” status.

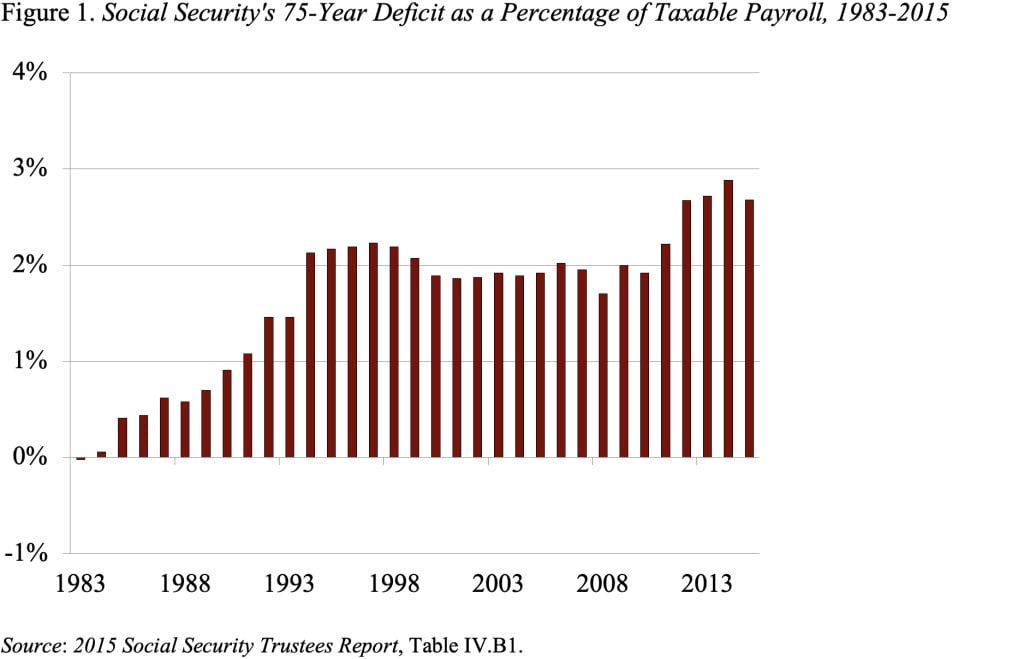

The two Myths I find most annoying are #1 and #9. Like the CRFB, I have always agreed with the notion that we should fix Social Security sooner rather than later. My reasons are twofold. First, eliminating the deficit will restore people’s faith in the program and make them feel more secure about retirement. Second, the timing of the adjustment affects which cohorts pay. If the change had been made in the early 1990s when a significant long-term shortfall first re-emerged (see Figure 1), the baby boom would have shared the burden with subsequent generations.

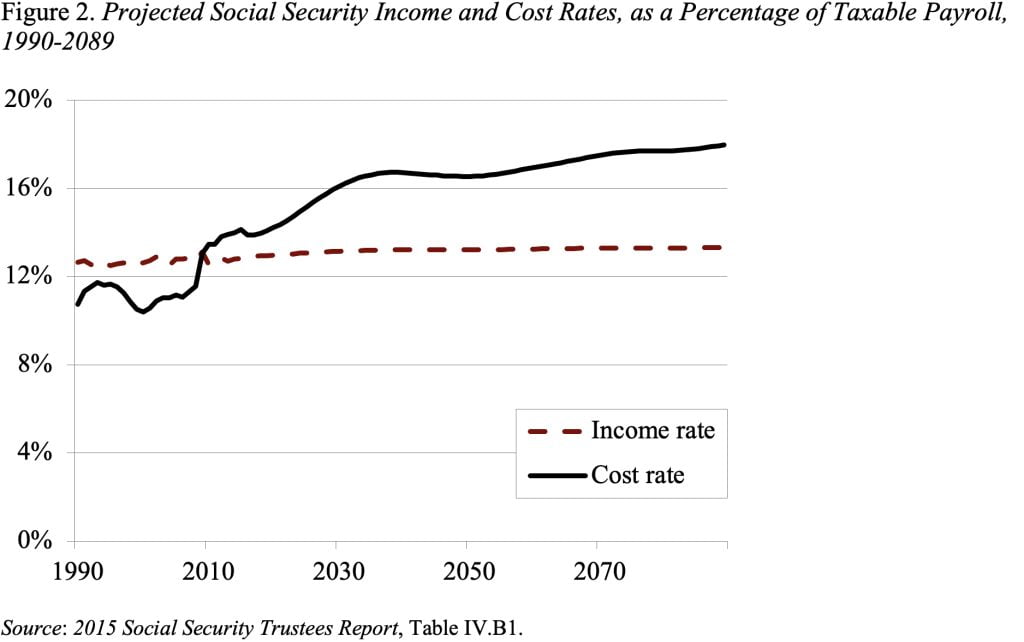

But claiming, as the Myth #1 response does, that postponing a fix raises the total cost of the fix is simply not correct. Figure 2 shows the income and cost rates for Social Security; the shortfall is the difference between these two lines. The total amount of the ultimate required tax increases is not impacted by the timing. The different numbers in the Myth #1 response simply apply to different 75-year projection periods – 2015-2090 versus 2034-2109.

Myth #9 is annoying because, while factually correct in a narrow sense, it does not acknowledge that a further increase in the Full Retirement Age would leave low-income early claimers with impossibly low benefits. Yes, the percentage change in benefits is proportional across income groups, but higher income workers can often work an additional year to offset the cut, while lower-income people have a much harder time doing so.

The only Myth I like is #4: Today’s workers will not receive Social Security benefits. Of course they will. Even if Congress makes no changes, current payroll taxes are sufficient to pay about 75 percent of promised benefits. But I guess it’s hard to have a list of Myths and Realities with only one item. While I like many of the budgeteers, I do worry when they turn their laser-like focus to Social Security.