Saving Social Security: Raising Taxes vs. Cutting Benefits

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Who knows what’s happening in Washington in the battle over raising the debt limit. One day they’re searching for $4 trillion in savings; the next day it’s $2 trillion. Sometimes Social Security is on the table; sometimes it’s not. Fixing Social Security could modestly help reduce the long-run deficit, but it is too important for millions of Americans simply to apply a meat ax. It should not be part of the discussion if revenues are off the table.

Social Security’s projected benefits exceed scheduled taxes. Opponents of including Social Security in the deficit reduction effort argue that, despite the mismatch of benefits and taxes, the program does not contribute to future deficits because, by law, it cannot spend money it does not have. Technically, they’re right. But, in fact, long-term deficit projections by the Congressional Budget Office, Office of Management and Budget, and Government Accountability Office all include the shortfall in their projections. And these projections matter because they are widely used by policymakers, investors, and the bond markets to gauge the nation’s fiscal health.

Therefore, eliminating Social Security’s shortfall will improve the long-term budget outlook. And it should be done sooner rather than later, because the longer we wait the bigger will be the required changes. Moreover fixing the program would make people feel more confident about their retirement future, and the impact of the required changes would not be felt until far in the future when we are well past the current lingering recession.

The key question is how much of Social Security’s financing gap should be closed by cutting benefits vs. raising taxes. My view is that retirements are at risk. The need for retirement income is increasing as people live longer, health care costs are soaring, and two-thirds will need some long-term care. At the same time, the retirement system is contracting. Social Security will replace less of pre-retirement income as the Full Retirement Age goes to 67, and employer-sponsored plans – for those lucky enough to have them – are increasingly 401(k)s with modest balances.

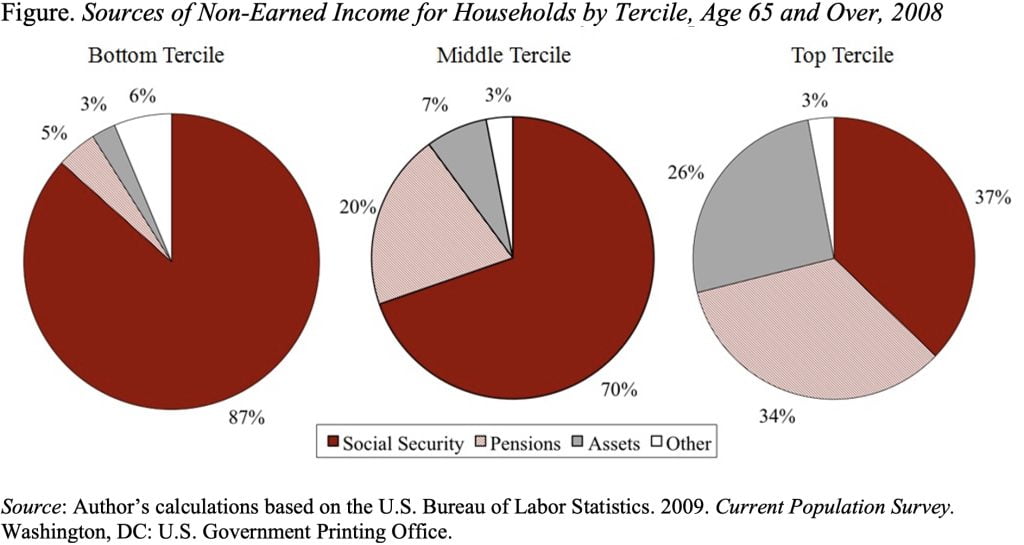

In this challenging environment, Social Security is the backbone of support for older Americans. As shown in the Figure, Social Security accounts for 87% of non-earned income for the poorest third of households 65 and over; 70% for the middle third; and 37% for the highest third. Given how much people rely on the program, we should be careful about large cuts in benefits.

Compromise is inevitable, however. And the best place to look for cost saving is increasing the retirement age. It’s hard to argue that if 66 is the right age today, it still will be the right age in 2050. Linking the Full Retirement Age (after it reaches 67) to improvements in longevity would make sure it goes up only if life expectancy increases and could be done very gradually.

But additional revenues are key to any Social Security deal. One popular proposal involves increasing the contribution and benefit base gradually to a level covering 90%of total national earnings – about $180,000 at current income levels. Another is a small increase in the payroll tax rate, by a fraction of one percent for the employer and employee. Others have suggested gradually eliminating the tax exclusion for group health insurance so that both employee and employer premiums are covered by the payroll (and income) tax.

In short, people rely too heavily on Social Security to make big benefit cuts. But we as a nation must pay for the benefits we want. So additional revenues have to be part of any plan to restore balance to Social Security. If that’s not possible, take it off the table.