Shoring Up Supplemental Security Income Would Help Many of the Nation’s Poorest

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

This relatively forgotten program, enacted in 1972, has withered on the vine.

A wise person used to argue that programs designed solely for poor people are poor programs – their benefits erode over time; unchanging income and asset tests reduce the eligible population; and they are expensive to administer. In contrast, programs like Social Security in which everyone participates and receives benefits are kept up to date with wage indexing of initial benefits, have no qualifying requirements, and involve administrative costs of less than 1 percent.

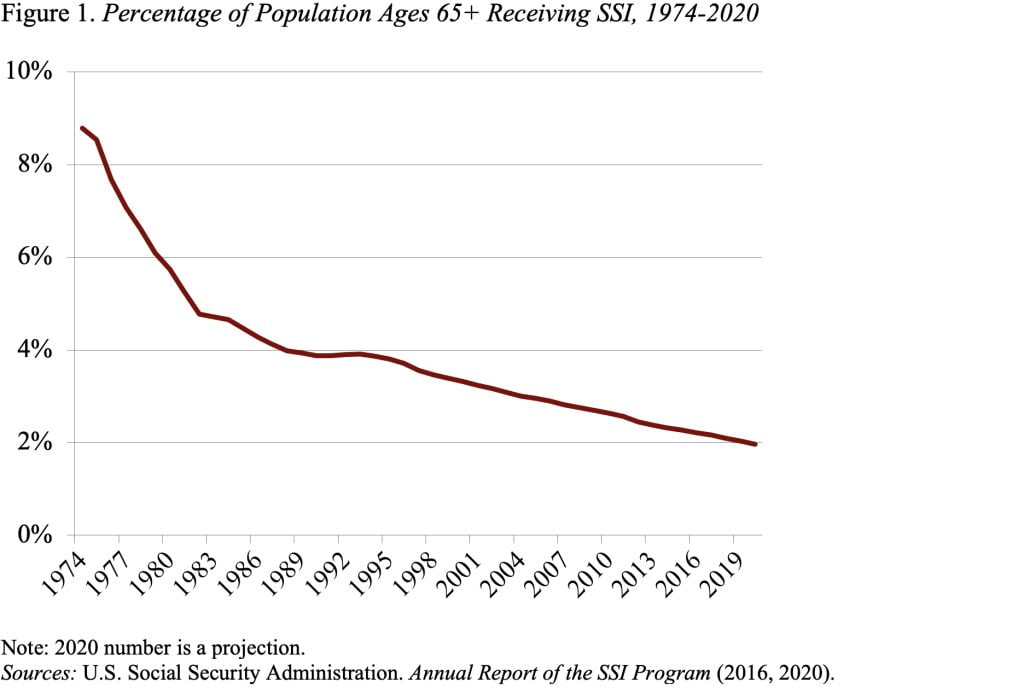

Nowhere is this assessment more true than the nation’s Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program, enacted in 1972 to nationalize the state welfare programs for adults ages 65+ and those with disabilities. The program, which began paying benefits in 1974, has not been kept up to date, and the percentage of the age 65+ population receiving SSI benefits has dropped from 9 percent to 2 percent (see Figure 1).

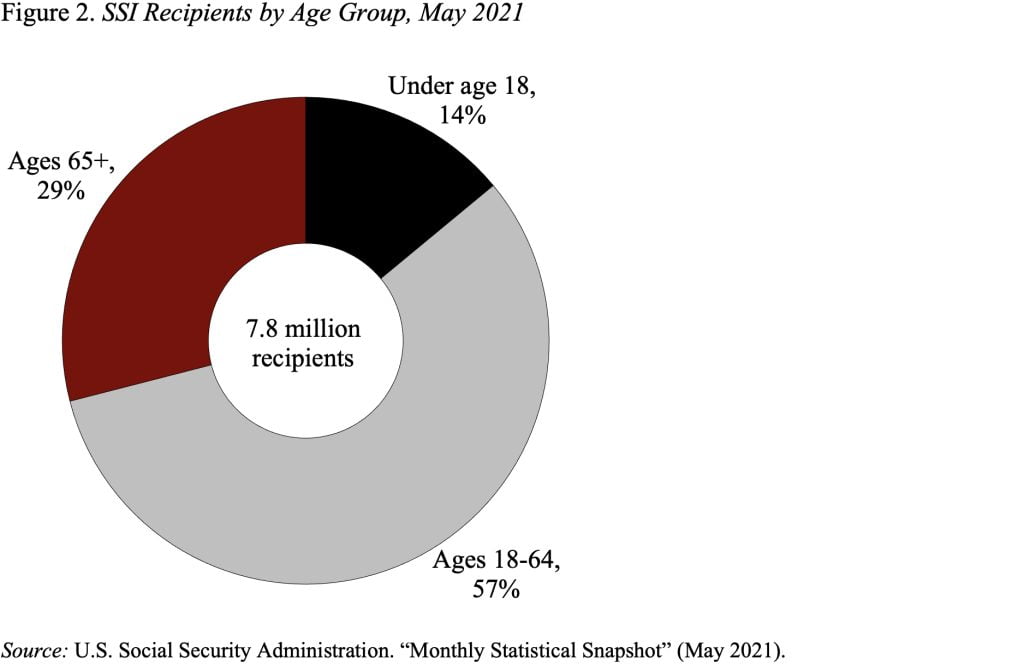

Today SSI enrolls relatively few people. The vast majority of beneficiaries qualify on the basis of disability (see Figure 2) – 4.5 million are non-elderly adults and 1.1 million are disabled children living in very low-income households. Another 2.3 million SSI beneficiaries are very poor older Americans.

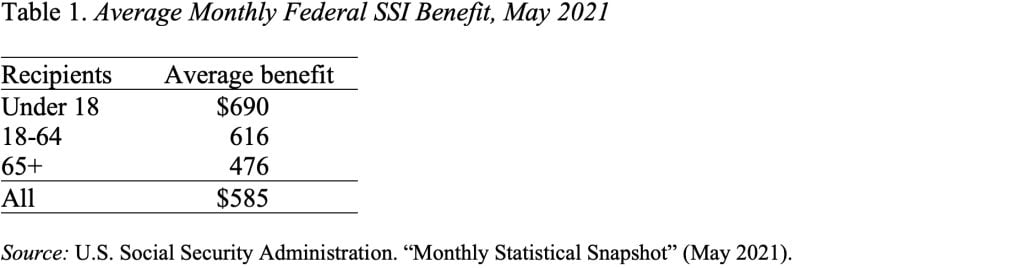

SSI also provides very modest benefits (see Table 1). The average federal benefit in 2021 is $585. Benefits are generally lower for those 65+ because they usually receive some Social Security payment, which reduces their benefit. Benefits for children are typically higher because they generally have no income of their own. In all cases, benefits are reduced by a third for beneficiaries who live in another person’s household without paying for shelter or food, under the “in kind support and maintenance” provisions.

In addition to the federal payment, some states also provide a supplementary benefit. Moreover, in most states SSI beneficiaries are eligible for Medicaid.

To be financially eligible for SSI, a person’s income and assets must be within defined limits. On the income side, all countable income received is subtracted from the federal benefit level. In 2021, the monthly maximum federal benefit is $794 for an individual and $1,191 for a couple. In calculating countable income, the program excludes the first $20 per month from any source and the first $65 of earned income plus one-half of earned income above $65 (amounts that have not been changed since 1974).

In terms of assets, the limits are $2,000 for an individual and $3,000 for a couple. The only exclusions are the person’s primary residence, household goods, and one car. The asset limits are not adjusted for inflation and have remained at their current levels since 1989.

In 2020, the Biden campaign proposed a reform of SSI involving four changes.

- Increase the federal benefit for a single person to the federal poverty line, set the benefit for a couple equal to twice that for a single person, and index for inflation going forward. Thus, the maximum benefit for a single person would rise from $794 under current law to $1,091 and for couples from $1,191 to $2,182.

- Increase the asset limits by the change in the Consumer Price Index since 1989, set the limit for couples equal to twice that for a single person, and increase for inflation thereafter. Thus, the asset limit in 2021 for a single person would increase from $2,000 to $4,300 and for a couple from $3,000 to $8,600.

- Update the income disregards ($20 from all sources and $65 of earned income) for inflation between 1974 and 2021 and index thereafter.

- Eliminate the “in-kind support and maintenance benefit reductions.”

Updating SSI is long overdue, and the beneficiaries of reform will be among the nation’s poorest and most vulnerable citizens.