Should Social Security Invest in Equities?

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Investing some of the Social Security trust fund’s assets in equities has always had obvious appeal. Equity investment has higher expected returns relative to safer assets, so Social Security might need less in tax increases or benefit cuts to achieve long-term solvency. On the other hand, equity investments involve greater risk and raise concerns about interference in private markets and about misleading accounting that suggests the government can get rich simply by issuing bonds and buying equities.

The real world provides a convincing case that governments can invest in equities in a sensible manner. Canada has a large actively managed fund, follows fiduciary standards, and uses conservative return assumptions. In the United States, the Railroad Retirement system has also invested in a broad array of assets without interfering in the private market, as has the Federal Thrift Savings Plan, where the government plays an essentially passive role.

But do the demonstrated successes mean that equity investment should be part of a solution for Social Security? Two developments suggest that the time may have passed.

First, the prerequisite for such activity is a trust fund with significant assets to invest. Social Security’s trust fund, which emerged from the 1983 amendments, is quickly heading towards zero. To recreate a trust fund would require a tax hike to cover both the program’s current costs and to produce an annual surplus to build up trust fund reserves.

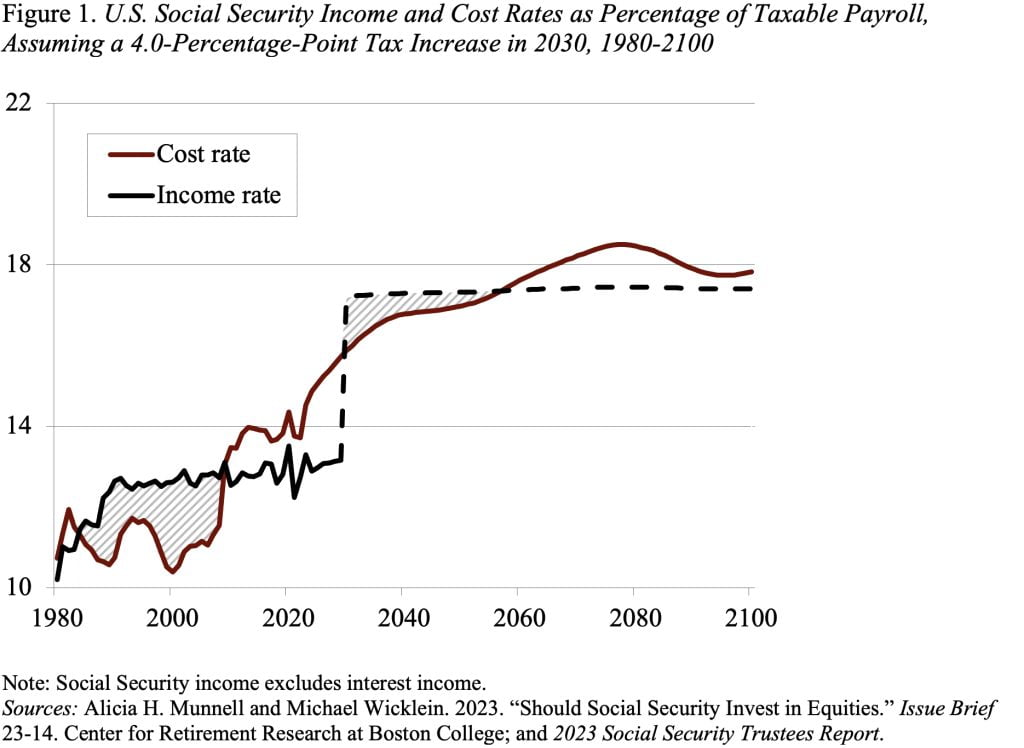

The problem is the cost curve is flattening out, so even if Congress raised the payroll tax rate by 4 percentage points starting in 2030 – approximately the amount needed to pay benefits over the next 75 years – it would produce only small temporary surpluses followed by cash-flow deficits thereafter. For context, these surpluses would be less than 40 percent of those produced by the 1983 legislation (see Figure 1).

Of course, in the unlikely event that action were taken much before 2030, the combination of current trust fund balances and the immediate surpluses generated by the tax increase could lead to meaningful accumulation. But it is not clear that the political will exists to make such a move.

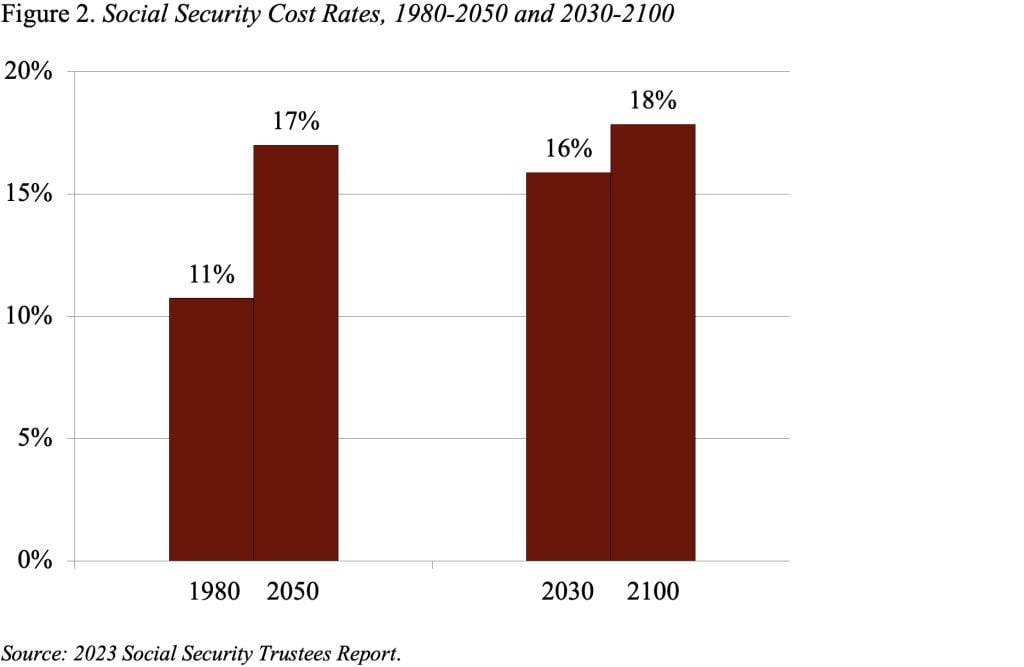

The second development pertains to intergenerational equity. Raising taxes in advance of the retirement of the baby boom served as a mechanism for equalizing the burden across generations. Workers in 1980 needed to pay 11 percent of taxable earnings to cover program costs, and workers in 2050 were scheduled to pay 17 percent. It made sense to have 1980-workers pay a bit more so that later workers could pay a bit less. But now costs have leveled off. Workers in 2030 face a cost rate of 16 percent, and workers in 2100 a cost rate of 18 percent. With costs scheduled to level off, it is hard to argue that today’s workers should pay more to build up a trust fund so that tomorrow’s workers would pay less.

The bottom line is that, while government investing trust fund assets in equities has been proven feasible, safe, and effective, rebuilding a trust fund at this time may not be either feasible or wise.