Should Social Security Invest in Equities?

The brief’s key findings are:

- Investing part of Social Security’s reserves in equities has obvious appeal: a higher return means less tax hikes or benefit cuts.

- But critics fear that equity investment could interfere with private markets or signal that trading bonds for stocks creates magic money.

- The evidence from the U.S. and Canada shows that such investing through government retirement funds is feasible, safe, and effective.

- While experience suggests that equities could work for Social Security, the time may have passed.

- Social Security’s trust fund is careening towards zero, and rebuilding the fund may not be wise or feasible.

Introduction

Investing some of the Social Security trust fund’s assets in equities has obvious appeal. Equity investment has higher expected returns relative to safer assets, so Social Security might need less in tax increases or benefit cuts to achieve long-term solvency. On the other hand, equity investments involve greater risk and raise concerns about interference in private markets and about misleading accounting that suggests the government can get rich simply by issuing bonds and buying equities.

The real world provides a convincing case that governments can invest in equities in a sensible manner. Canada has a large actively managed fund, follows fiduciary standards, and uses conservative return assumptions. In the United States, the Railroad Retirement system has also invested in a broad array of assets without interfering in the private market, as has the Federal Thrift Savings Plan, where the government plays an essentially passive role.

But do the demonstrated successes mean that equity investment should be part of a solution for Social Security? The prerequisite for such activity is a trust fund with significant assets to invest. The current trust fund is rapidly heading to zero; the likelihood of raising taxes to rebuild it is low; and borrowing to do so does not guarantee any additional resources for Social Security.

The discussion proceeds as follows. The first section provides background on motivation for equity investment and the concerns of the critics. The second section describes investing initiatives by three retirement plans – the Canada Pension Plan, the Railroad Retirement system, and the Federal Thrift Savings Plan – and evaluates them against the critics’ concerns. The third section explores whether, even if the concerns were addressed, equity investment could be part of a package to restore financial stability to Social Security. The final section concludes that while the mechanics are totally manageable, the time may have passed for raising taxes enough to accumulate a large enough trust fund to make the effort worthwhile.

Background

In the United States, serious discussion of equity investments for Social Security arose as 75-year deficits reemerged in the wake of the 1983 amendments. President Clinton asked the 1994-1996 Advisory Council on Social Security to consider options to achieve long-term solvency. The Council could not agree on a single plan, so its members advanced three different proposals to close the funding gap. All three included some form of investment in equities. Two involved equity investment through individual accounts, and the third recommended that a portion of the trust fund reserves be invested directly in equities.

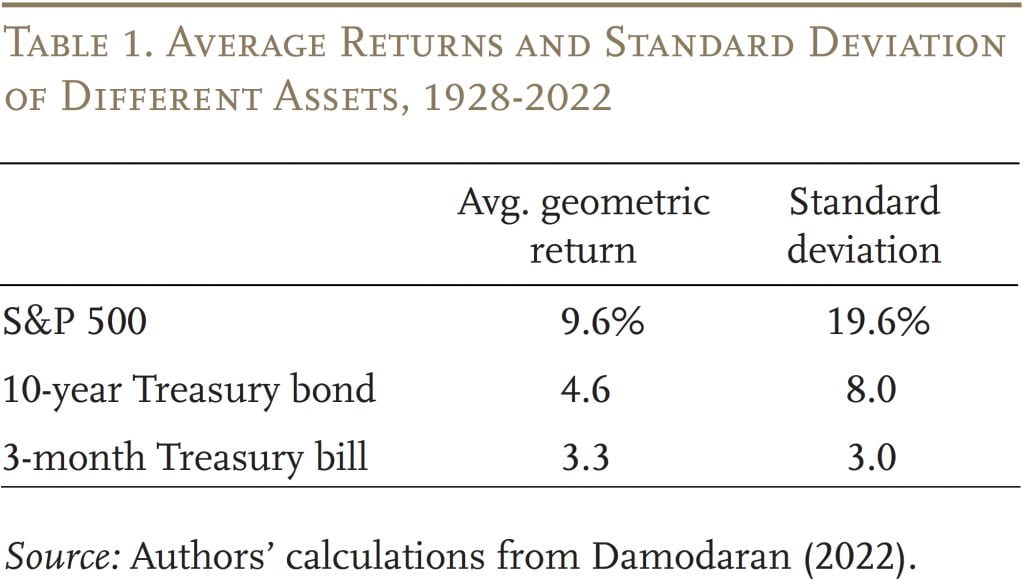

The major attraction of equity investment is that it has a higher expected rate of return relative to safer assets, such as Treasury bonds or bills, so that restoring balance to Social Security would require less in tax increases or benefit cuts (see Table 1). Economists also argue that efficient risk-sharing across a lifecycle requires individuals to bear more financial risk when young and less when old, and since the young have little in the way of financial assets, investing the trust fund in equities is one way to achieve that goal.

Critics are concerned that Social Security equity investing would have adverse effects on the stock market and corporate decision-making, and create the impression that trading bonds for stocks provides magic money. Any assessment involves answering the following questions:

- How big is the equity investment initiative compared to the economy? If Social Security had begun investing in the stock market in 1984 or 1997, according to a 2016 study, it would own about 4 percent of the market.1Burtless et al. (2016). As a point of comparison, state and local pension plans currently hold about 5 percent of total equities.

- How do government officials choose the investments? Proponents of trust fund equity investment on the 1994-1996 Advisory Council assumed that the government would take a very passive role. But, as discussed below, the Canada Pension Plan and the Railroad Retirement system take a much more active approach.

- Do government agencies use expected returns or risk-adjusted returns to evaluate the impact of equities on plan finances? Crediting expected returns quantifies the potential contribution of equities to solving Social Security’s financing shortfall, but suggests that the government could mint money simply by selling bonds and buying stocks. Adjusting for risk avoids the impression that returns are guaranteed, but shows no impact of equity investment on the system’s finances at the time of adoption. Higher returns are booked only after they are realized.

The following takes a closer look at three retirement plans engaged in equity investment and assesses the extent to which they address the critics’ concerns.

Three Federal Government Plans with Equity Investments

The discussion starts with the Canada Pension Plan, which has a large actively managed fund engaged in a wide range of investments. While the Canadian experience is impressive and even enviable, it most likely involves more even quasi-government investment activity than Americans could tolerate. So, the focus shifts to two U.S. plans – the Railroad Retirement system, a relatively small plan also with a broad investment portfolio, and the Federal Thrift Savings Plan, a defined contribution plan for public employees and military personnel, where the government merely selects the plan’s investment options.

Canada Pension Plan

The Canada Pension Plan, the major component of Canada’s retirement system, was initially set up in 1966 as a pay-as-you-go plan with a modest reserve, similar to the U.S. Social Security program.2The CPP covers workers across all Canadian provinces, with the exception of Québec. The program is primarily financed by employee and employer contributions, each paying half of the contribution rate. Benefits are based on contribution amounts, contribution years, and beneficiary age. In addition to the CPP, Canada has two other public programs that contribute significantly to retirees’ income. The first is the Old Age Security (OAS) program, a universal pension financed through general revenues. The second is the Guaranteed Income Supplement, which provides low- and moderate-income retirees an additional benefit over and above the OAS payments and is also funded through general revenues. This approach made sense with a young population and rapidly growing wages. However, within a few decades, lower birth rates, longer life expectancies, and lower real wage growth led to increasing plan costs, with the prospect of rapidly rising payroll contribution rates going forward.3In 1993, the Chief Actuary projected that the contribution rate would need to increase from the then-current level of 5.0 percent to 14.2 percent by 2030.

A dramatic increase in contribution rates over time ran counter to Canadian notions of intergenerational equity.4Federal, Provincial and Territorial Governments of Canada (1996a and 1996b); and Pesando (2001). To improve fairness across generations and ensure the long-term financial sustainability of the plan, Canada enacted legislation in 1997 that increased payroll contributions to its projected long-term rate and began investing some of the fund accumulations in equities. It also required that any changes to the plan going forward had to be fully funded.

To implement the investment strategy, the 1997 legislation created the CPP Investment Board (CPPIB).5The CPPIB is also known as CPP Investments. While it is a government-owned corporation, CPPIB is managed independently from the CPP itself and operates at arm’s length from governments.6The 1997 legislation defined an elaborate set of procedures to make the CPPIB as independent from the government as possible and instituted reporting requirements to ensure transparency and public accountability. The Board’s mandate is to invest CPP revenues not needed to pay current benefits to achieve the maximum return, without incurring undo risk, for the sole benefit of CPP contributors and beneficiaries.7To name the members of the Investment Board, the Minister of Finance consults with the appropriate provisional Ministers of the participating provinces. Together they form a committee that advises the Minister of Finance before making recommendations to the Governor in Council. Candidates for the Investment Board may not be government officials and must have “proven financial ability” and “relevant work experience.” Once selected, directors on the Investment Board serve three-year terms with the possibility of reappointment.

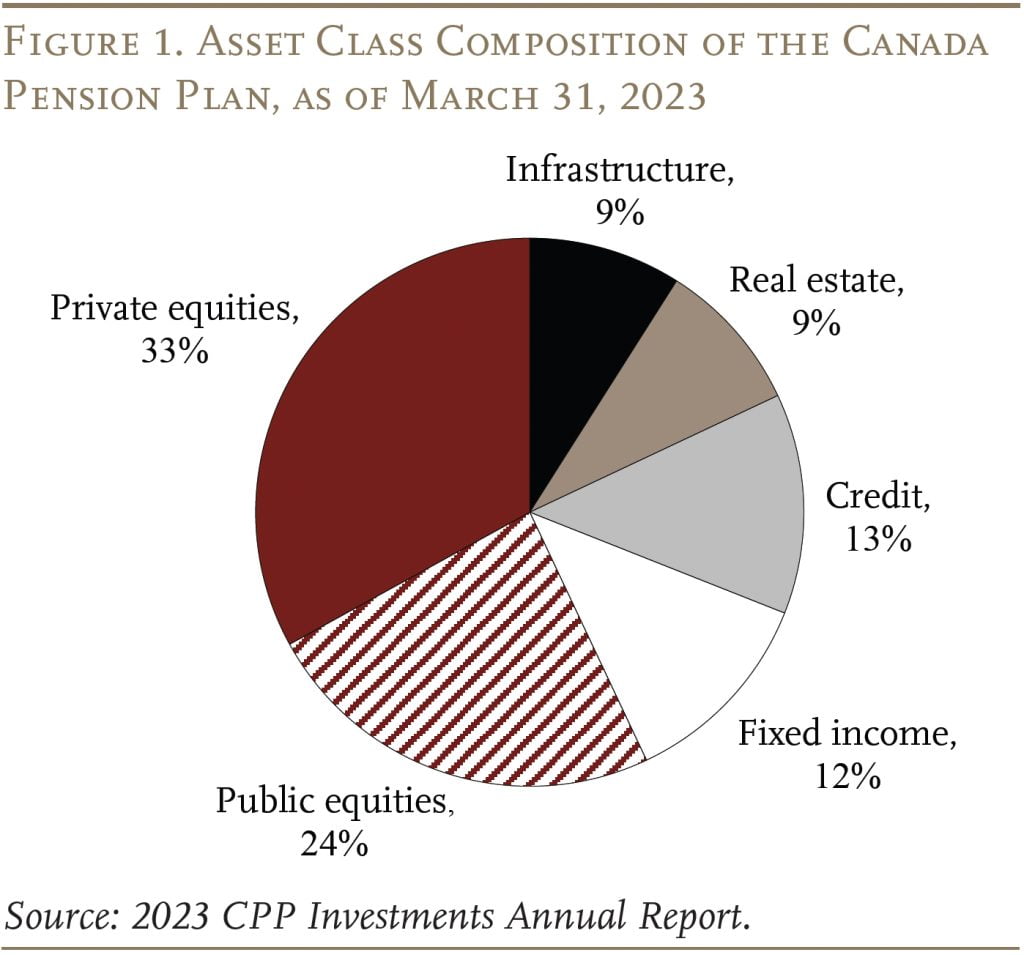

The CPPIB has built a broad-based portfolio that includes not just investments in stocks and bonds, but also real estate, infrastructure projects, and private equity (see Figure 1). Total assets amount to 570 billion CAD in 2023.

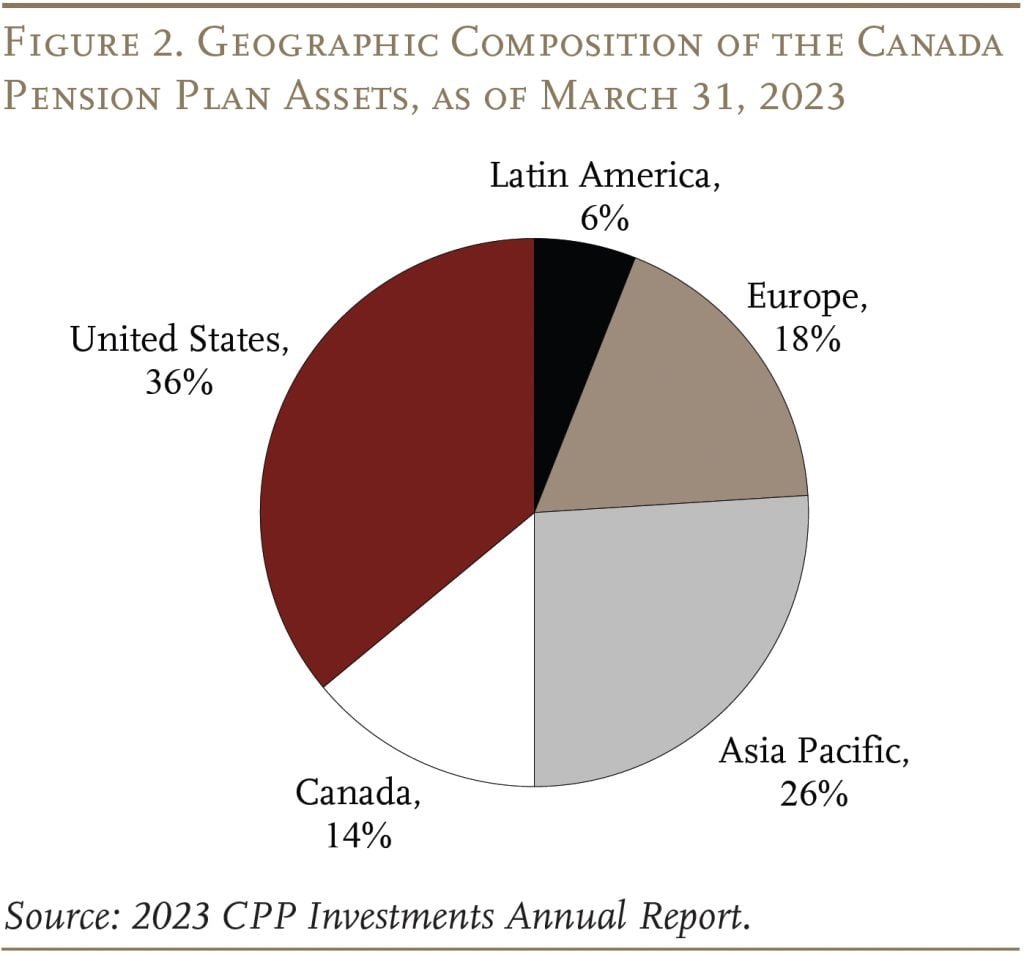

To mitigate exposure of the Fund to risks related to future Canadian economic and demographic conditions, the CPPIB diversifies its investments across the world (see Figure 2). Thus, the Fund’s domestic investments are small relative to its GDP (2.8 trillion CAD) and its stock market (3.9 trillion CAD).

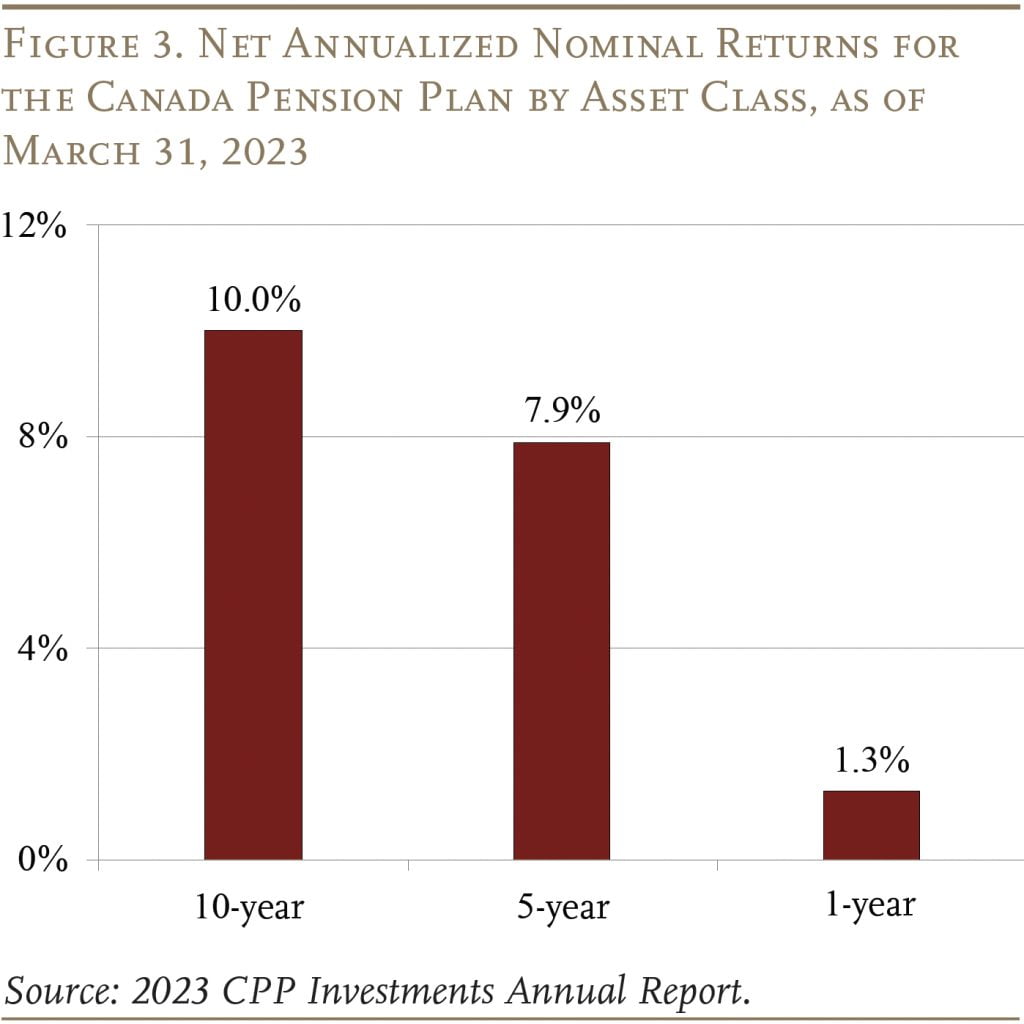

While the CPPIB has one fund, it has six departments that invest and manage the assets. The managers are in-house, highly-compensated individuals. Over the last ten years, the Fund had an annualized net return of 10 percent (see Figure 3).

The CPPIB does include economic, social, and governance considerations in its investment decisions when the managers believe that addressing such issues will generate superior returns in the long run. The Board publicly votes proxies at annual meetings and encourages companies to consider climate risk and develop viable transition strategies. It does not engage in blanket divestment from companies in high-emitting sectors because the managers think that they would then lose the ability to use the CPPIB’s influence constructively.

The Board thinks about risk in terms of both a minimum and a target (see Table 2). The minimum level of risk for the base CPP would be a portfolio of 50-percent Canadian government bonds and 50-percent global public equities. In 2016, Canada passed legislation that would increase CPP contributions and benefits. The minimum risk levels for this additional component are somewhat lower: 60-percent bonds and 40-percent global equities.

The rate of return assumptions used in the actuarial reports have been conservative, as actual investment earnings have routinely exceeded projected earnings. Under these cautious assumptions, the base CPP and additional CPP components have both been projected to be sustainable for the 75-year period. An additional safeguard kicks in if the actuaries project that the system’s finances are not in balance. If policymakers fail to address the projected imbalance, contribution rates increase and benefit indexation is frozen.

The bottom line is that the Canadian investment initiative has paid off, while addressing the concerns of critics. Investments represent a small share of the Canadian economy; they are governed by strict fiduciary standards; the Board uses its influence in the private sector only to enhance long-run returns; and the assumed investment returns used for evaluating the solvency of the CPP are on the conservative side.

U.S. Railroad Retirement System

Congress created the Railroad Retirement system in 1934, when it took over the rail industry’s tottering pension plan. The program was funded on a pay-as-you-go-basis financed by a payroll tax on workers and employers. It had a modest trust fund with assets invested solely in government bonds. In the 1990s, however, assets in the program’s trust fund had grown to four times annual outlays, a historically high level, and the notion was that it could grow even higher with the use of equities. So, management and labor negotiated a proposal to invest the Railroad Retirement assets in equities. Since Railroad Retirement is a government program, management and labor had to convince Congress to enact their plan.

Congress’ primary concern was the risk of political influence on investment decisions.8With the addition of risky assets, Congress was also concerned about the program’s finances, so the management/labor proposal included an automatic adjustment mechanism. This mechanism would raise or lower payroll taxes to keep the ratio of assets to outlays, averaged over the last ten years, within a target band of four to six. To address this concern, Congress created the National Retirement Investment Trust (NRRIT) with management and labor each selecting three trustees, who, in turn, would then select a seventh independent trustee. Congress also imposed a private-sector fiduciary mandate on these trustees, requiring them to invest the government’s assets solely in the interest of plan participants. The trustees initially allocated 65 percent of trust fund assets to equities. Over time, NRRIT has broadened its portfolio beyond equities to include real estate, private equity, and private debt. In 2023, net assets in the trust fund were $27 billion. The actual investing is delegated to external managers.

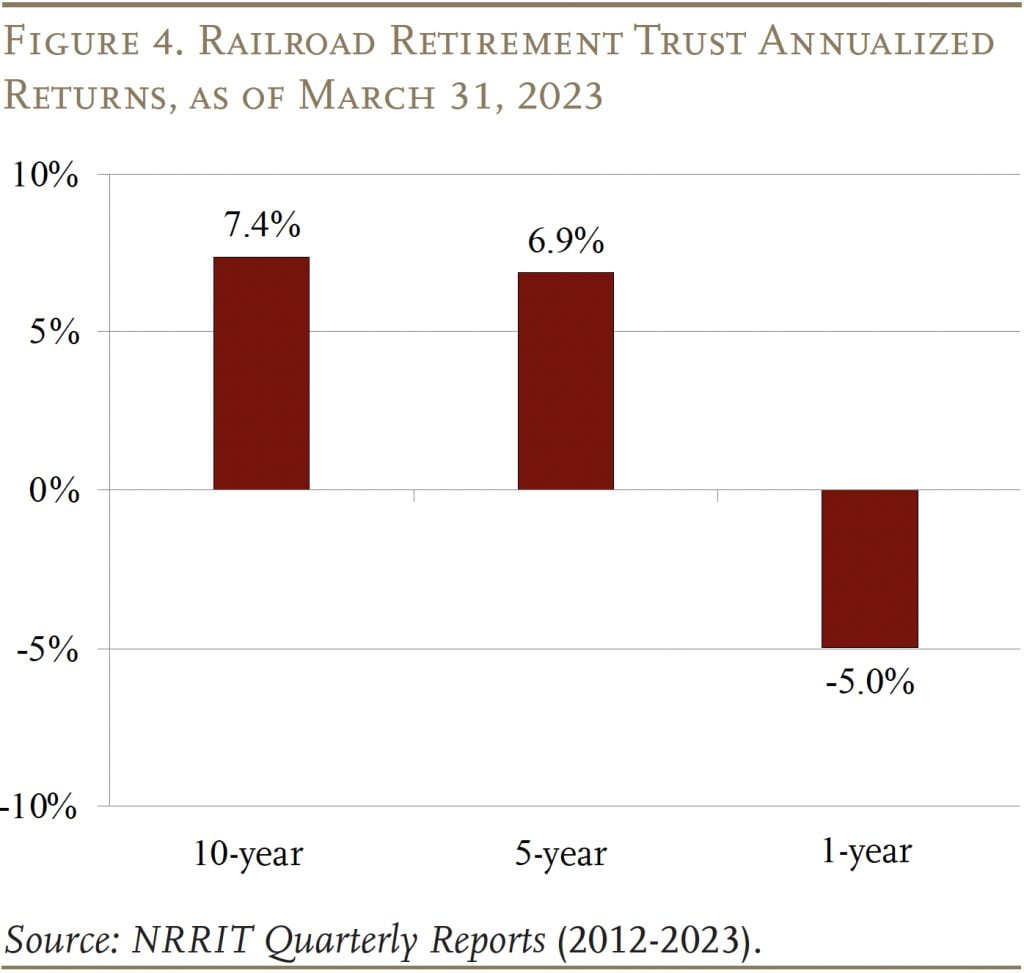

The issue arose on how to evaluate the use of equities in reform proposals. While the Social Security actuaries credit equities with their expected rate of return, the Office of Management and Budget, in evaluating the financial implications of the Railroad Retirement proposal, ignored the higher expected return on equities and used a risk-adjusted return – the long-term Treasury rate – to project future Trust Fund balances. Today, the Railroad Retirement actuaries assume a 6.5-percent return, a compromise between the actual returns and a risk-adjusted rate (see Figure 4).

Federal Thrift Savings Plan

The Federal Thrift Savings Plan (TSP), established in 1986, currently has 6.5 million participants and about $800 billion in assets. From the beginning, members of Congress were concerned that the Executive Branch would pressure the plan fiduciaries to select investment options to further its own policy goals. In response, Congress established elaborate guardrails.

The Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board, which administers the TSP, has far less discretion than other plan fiduciaries in setting investment policy. While other fiduciaries can determine the number and types of investment funds, Congress has established the options that the Board can offer and must approve any expansion or change.9The options include a government bond fund, a fixed income fund, a common stock index fund, a small cap stock index fund, and an international stock index fund, as well as several target date funds that include a mix of these assets. Moreover, when choosing benchmark indices for the investment funds, the Board is limited to those that are “commonly recognized” and which are a “reasonably complete representation” of the entire market. The Board is prohibited from removing any stock from the index. In addition, the Board is categorically prohibited from using proxy voting power to influence corporate decision-making.

Francis Cavanaugh, the first executive director of the TSP’s Board, reported that it had no difficulties in selecting an index and obtaining competitive bids from large index fund managers. And he encountered no issues of government interference in the market. In short, a model already exists for structuring Social Security investment in equities – passive investment through index funds and no proxy voting.

Does Equity Investment Make Sense in 2023?

In theory the answer is “yes.” Those plans that have adopted equities have enjoyed substantially higher returns than bond yields, despite the dot-com recession and the financial crisis. In terms of critics’ concerns, the experience with the TSP provides a road map for separating the government from actual investment decisions, and accounting for returns on a somewhat risk-adjusted basis – like the Railroad Retirement system – would avoid the appearance of easy money.

But investing trust fund assets in equities requires having a sizable trust fund. Social Security’s trust fund, which emerged from the 1983 amendments, is quickly heading towards zero. To recreate a trust fund would require a tax hike to cover both the program’s current costs and to produce an annual surplus to build up trust fund reserves.

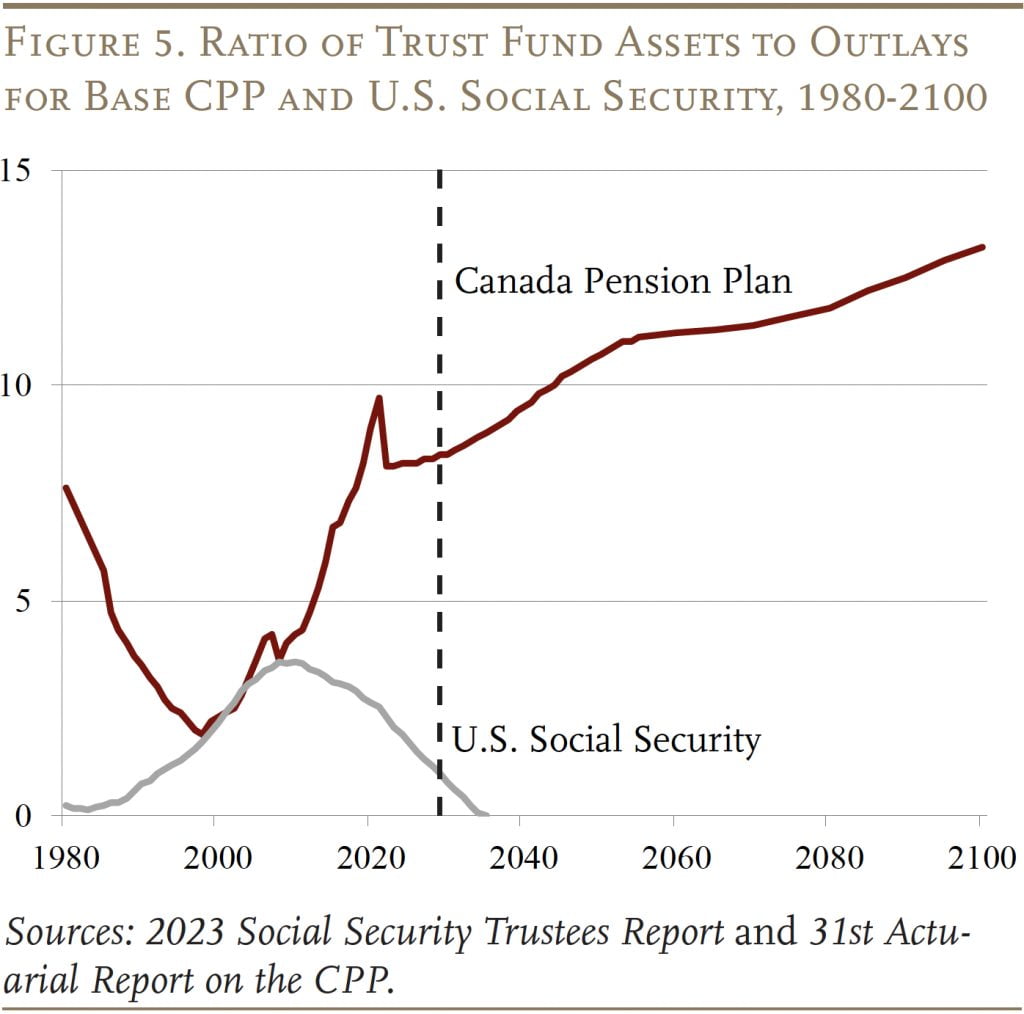

Such an initiative is not unprecedented; both the United States in 1983 and, as noted, Canada in 1997 raised payroll contributions above current program costs and accumulated fund assets (see Figure 5). Raising taxes in advance of the retirement of the baby boom served as a mechanism for equalizing the burden across generations.

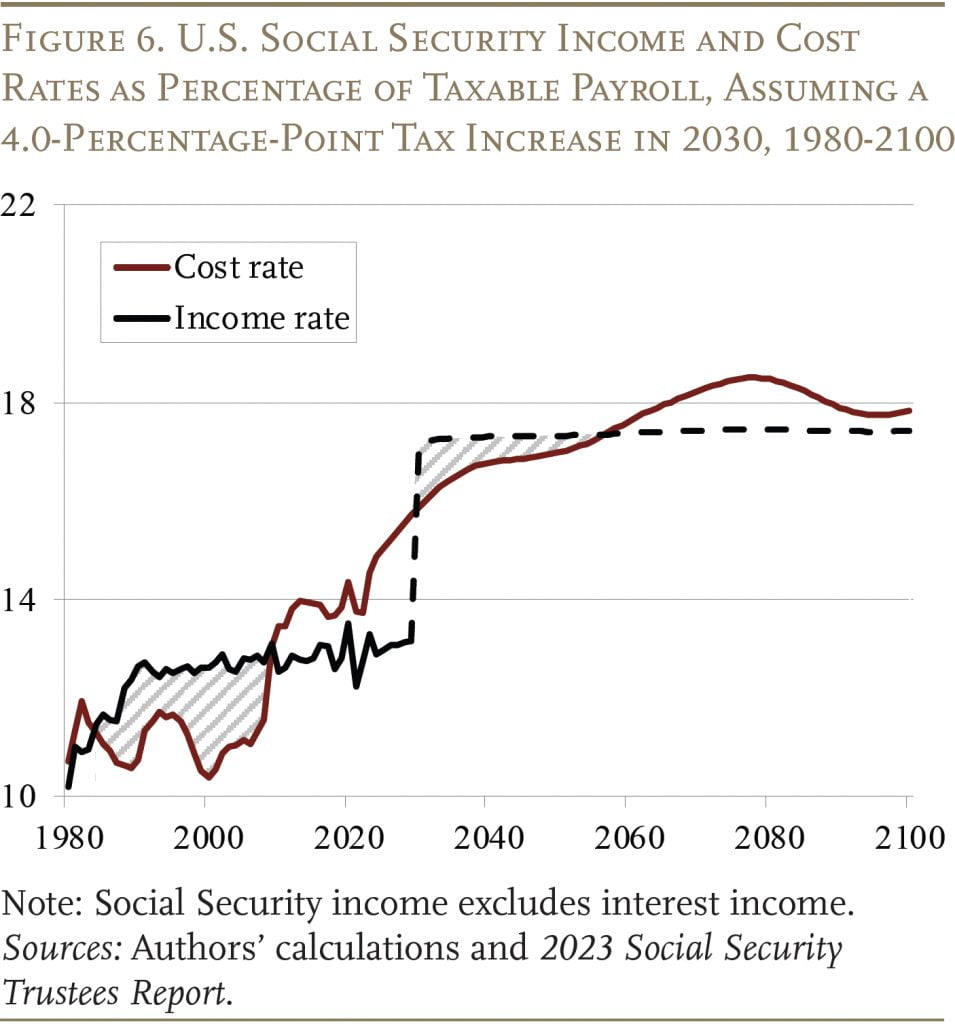

The situation now is quite different than it was in 1983. Most of the cost increase is behind us so even if Congress raised the payroll tax rate by 4 percentage points starting in 2030 – approximately the amount needed to pay benefits over the next 75 years – it would produce only small temporary surpluses followed by cash-flow deficits thereafter. For context, these surpluses would be less than 40 percent of those produced by the 1983 legislation (see Figure 6).

Of course, in the unlikely event that action were taken much before 2030, the combination of current trust fund balances and the immediate surpluses generated by the tax increase could lead to meaningful accumulation.

But it is not clear that the political will exists to make such a move, nor is the case for building up a large trust fund compelling. With costs scheduled to level off, it is hard to argue that today’s workers should pay more to build up a trust fund so that tomorrow’s workers would pay less.

If Congress is unwilling to raise taxes enough to create a meaningful trust fund, how about borrowing? Indeed, one proposal would have the government borrow about $1.5 trillion and invest those funds in stocks, private equity, and other instruments that offer higher expected returns than interest on government debt.10Cassidy (2023). In the meantime, the government would also borrow to cover Social Security’s shortfall. After 75 years, money from the trust fund could be used to repay the borrowing that went towards paying benefits.

This proposal differs fundamentally from the approach in Canada, which involves actually contributing more money to build up a reserve fund for the future. In contrast, creating a trust fund on borrowed money, which the government must repay with interest, means that the only proceeds are any earnings in excess of the interest paid on the bonds. Fixing Social Security requires real economic changes – cutting benefits or increasing income. This proposal offers nothing except the chance to pocket the return in excess of the bond rate.

Some have likened the proposal to advising a middle-aged couple who realize that they have not saved enough for retirement not to cut back on their spending, plan to spend less once they retire, or work longer, but rather to take out a really large loan and put it in the stock market. No financial planner would suggest such a strategy, and the proposal to borrow is no more sensible for the country than borrowing-to-invest is for the couple.

The bottom line is that the prerequisite for investing in equities – namely, having a meaningful trust fund – is not likely to emerge. It would have been a terrific idea in 1983 or even later. But the United States passed up that opportunity, and it may be too late for such an initiative.

Conclusion

The notion of governments investing in equities through retirement program trust funds is a viable concept that has been proven feasible, safe, and effective in both Canada and the United States. So, in theory, this idea could work with the U.S. Social Security program.

But one critical component is currently missing: Social Security no longer has a sizable trust fund to invest. And rebuilding the trust fund through additional taxes or borrowing may not be either wise or feasible. Thus, while the mechanics are totally manageable, the time may have passed for raising taxes enough to accumulate a meaningful Social Security trust fund that would make investing in equities worthwhile.

References

Advisory Council on Social Security. 1997. 1994-1996 Advisory Council on Social Security: Findings and Recommendations. Volumes I and II. Washington, DC.

Burtless, Gary, Anqi Chen, Wenliang Hou, and Alicia H. Munnell. 2016. “How Would Investing in Equities Have Affected the Social Security Trust Fund?” Working Paper 2016-6. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Canada Pension Plan Board Act. S.C. 1997, c.40. Ottawa, Canada: Government of Canada, Justice Laws Website.

Cassidy, Bill. 2023. “Refusing to Reform Social Security Is a Plan – and a Bad One.” (May 9). New York, NY: National Review.

CPP Investments. 2023. Annual Report. Toronto, Canada.

Damodaran, Aswath. 2022. “Historical Returns on Stocks, Bonds, and Bills – United States.” New York, NY: New York University, Stern School of Business.

Federal, Provincial and Territorial Governments of Canada. 1996a. An Information Paper for Consultations on the Canada Pension Plan. Ottawa, Canada.

Federal, Provincial and Territorial Governments of Canada. 1996b. Report on the Canada Pension Plan Consultations. Ottawa, Canada.

Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board. 2022. Request for Information on Possible Agency Actions to Protect Life Savings and Pensions from Threats of Climate Related Risk. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor.

National Railroad Retirement Investment Trust. 2012-2023. Quarterly Updates. Washington, DC.

Office of the Chief Actuary, Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada. 2022. 31st Actuarial Report on the Canada Pension Plan as at 31 December 2021. Ottawa, Canada: Minister of Public Works and Government Services.

Pesando, James. 2001. “The Canada Pension Plan: Looking Back at the Recent Reforms.” In The State of Economics in Canada: Festschrift in Honour of David Slater, edited by Patrick Grady and Andrew Sharpe, 137-150. Ottawa, Canada: Queen’s University, John Deutsch Institute and the Centre for the Study of Living Standards.

U.S. Social Security Administration. 2023. The Annual Reports of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Endnotes

- 1Burtless et al. (2016).

- 2The CPP covers workers across all Canadian provinces, with the exception of Québec. The program is primarily financed by employee and employer contributions, each paying half of the contribution rate. Benefits are based on contribution amounts, contribution years, and beneficiary age. In addition to the CPP, Canada has two other public programs that contribute significantly to retirees’ income. The first is the Old Age Security (OAS) program, a universal pension financed through general revenues. The second is the Guaranteed Income Supplement, which provides low- and moderate-income retirees an additional benefit over and above the OAS payments and is also funded through general revenues.

- 3In 1993, the Chief Actuary projected that the contribution rate would need to increase from the then-current level of 5.0 percent to 14.2 percent by 2030.

- 4Federal, Provincial and Territorial Governments of Canada (1996a and 1996b); and Pesando (2001).

- 5The CPPIB is also known as CPP Investments.

- 6The 1997 legislation defined an elaborate set of procedures to make the CPPIB as independent from the government as possible and instituted reporting requirements to ensure transparency and public accountability.

- 7To name the members of the Investment Board, the Minister of Finance consults with the appropriate provisional Ministers of the participating provinces. Together they form a committee that advises the Minister of Finance before making recommendations to the Governor in Council. Candidates for the Investment Board may not be government officials and must have “proven financial ability” and “relevant work experience.” Once selected, directors on the Investment Board serve three-year terms with the possibility of reappointment.

- 8With the addition of risky assets, Congress was also concerned about the program’s finances, so the management/labor proposal included an automatic adjustment mechanism. This mechanism would raise or lower payroll taxes to keep the ratio of assets to outlays, averaged over the last ten years, within a target band of four to six.

- 9The options include a government bond fund, a fixed income fund, a common stock index fund, a small cap stock index fund, and an international stock index fund, as well as several target date funds that include a mix of these assets.

- 10Cassidy (2023).