Social Security 2021 Trustees Report Is Complicated

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

But bottom line is easy: Congress needs to fix the nation’s most valuable program.

The 2021 Social Security Trustees Report, which usually comes out in the spring, emerged in the last week in August. That’s not surprising given a new Administration and a somewhat more complicated story than usual.

Although the Trustees assert that COVID and the ensuing recession had “significant effects” on Social Security’s finances, it is hard to see much of an impact in the report. In the short term, employment, earnings, interest rates, and GDP, which all dropped substantially in 2020, are expected to return to their pre-COVID levels by 2023, and births delayed in 2020-22 are assumed deferred to 2024-26. The increase in deaths due to COVID actually improve the system’s finances.

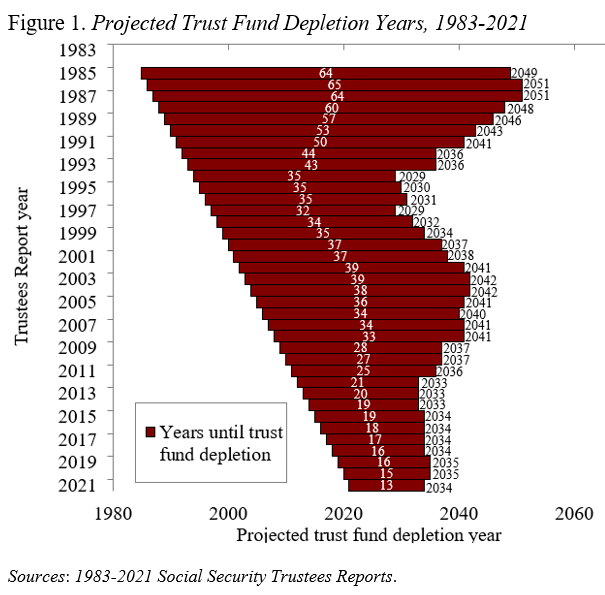

As a result, the depletion date for the trust fund moved up by only one year from 2035 to 2034. That’s not really big news. Virtually since inception the Trustees have projected its demise. The point is that the window of opportunity to restore balance has narrowed dramatically over time (see Figure 1).

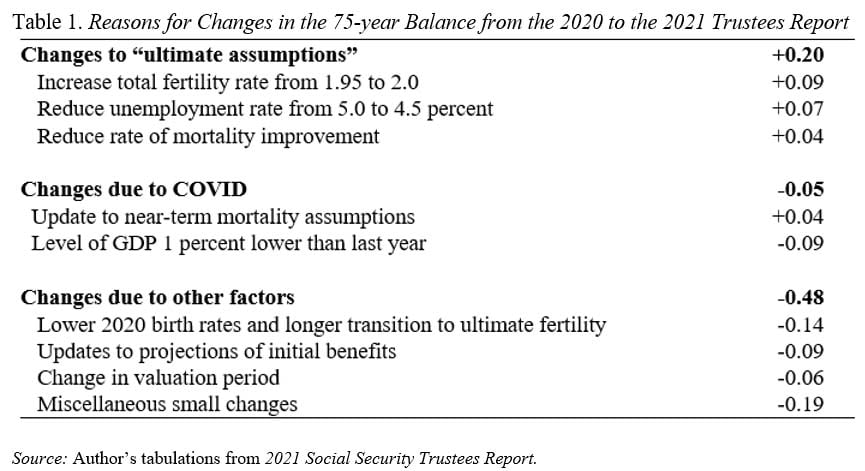

For the 75-year projection, given the uncertainty about the ultimate impact of COVID, the Trustees assume that the pandemic and recession would have no effect on the 75-year ultimate assumptions. The three changes they did make to the ultimate assumptions – raising the total fertility rate, lowering the rate of mortality improvement, and lowering the unemployment rate – all improve the outlook substantially (see Table 1).

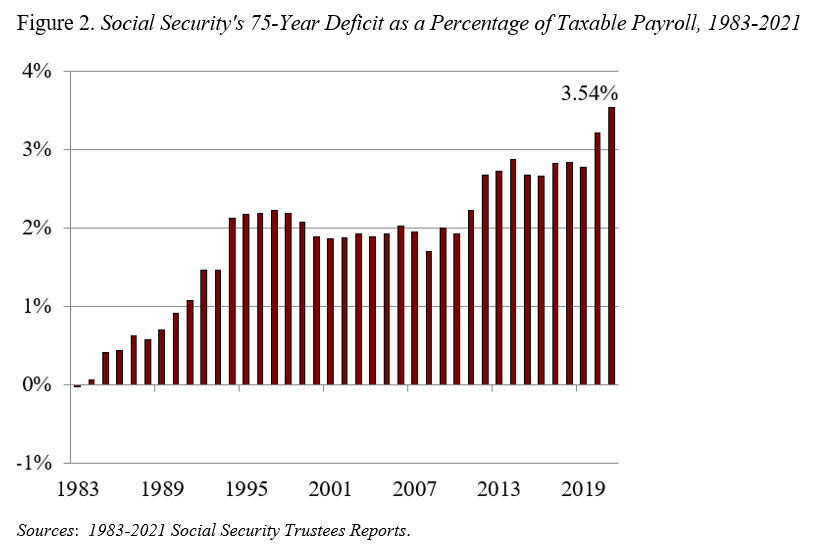

Yet, the 75-year deficit increased from 3.21 to 3.54 percent of taxable payrolls. The biggest movers were: 1) fewer births than expected in 2020 and recognition that women will continue to delay childbearing; 2) a 1-percent decline in the level of potential GDP due to COVID and the accompanying recession; 3) updates to projections of initial benefits; and 4) moving the valuation period ahead one year. These major changes plus a host of smaller ones produced the largest deficit since the 1983 reforms (see Figure 2).

The bottom line is that the 75-year deficit has increased, and it is not primarily due to COVID. At the same time, Social Security has once again demonstrated its worth during these tumultuous times, when – in the face of economic collapse – it continued to provide steady income to retirees and those with disabilities. To maintain confidence in this valuable program and avoid precipitous cuts in 2034, Congress needs to address the program’s 75-year deficit.