Social Security Benefits Have Been Earned and Will Be in the Future

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Benefit/contribution ratios provide no guidance on how to fix Social Security.

Two of my friends – Andrew Biggs (“No, Social Security Isn’t Earned”) and Gene Steuerle (“Lifetime Social Security Benefits and Taxes”) are making my brain ache. They are both arguing that people will get lifetime Social Security benefits far in excess of lifetime contributions, and the “unearned” portion of future benefits should be on the chopping block.

Let me make three snippy comments and then address the underlying issue.

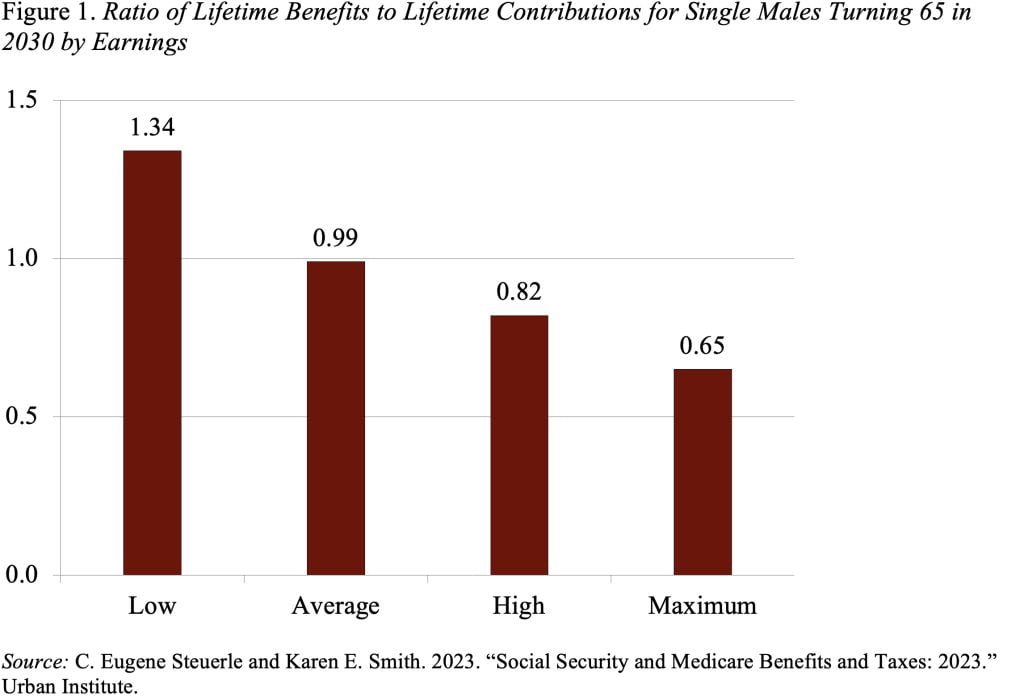

First, the people who receive benefits in excess of contributions are not the group that anyone would target for cuts (see Figure 1).

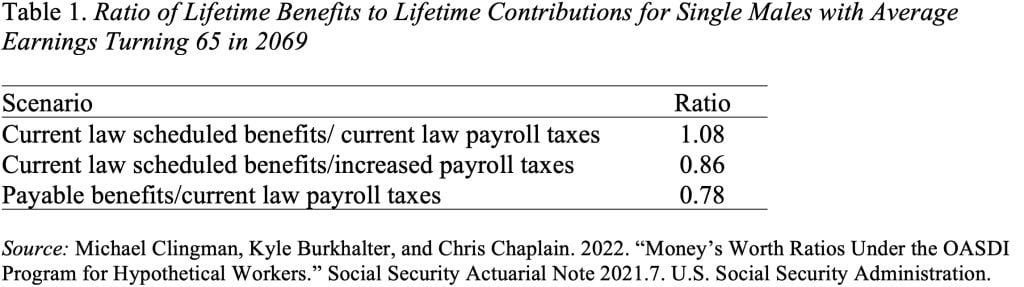

Second, any exercise that looks at scheduled benefits and current taxes after 2030 is misleading, since the program cannot pay scheduled benefits without new revenue. Hence, the Social Security actuaries include “increased-tax” and “reduced-benefit” scenarios, which totally change the story (see Table 1).

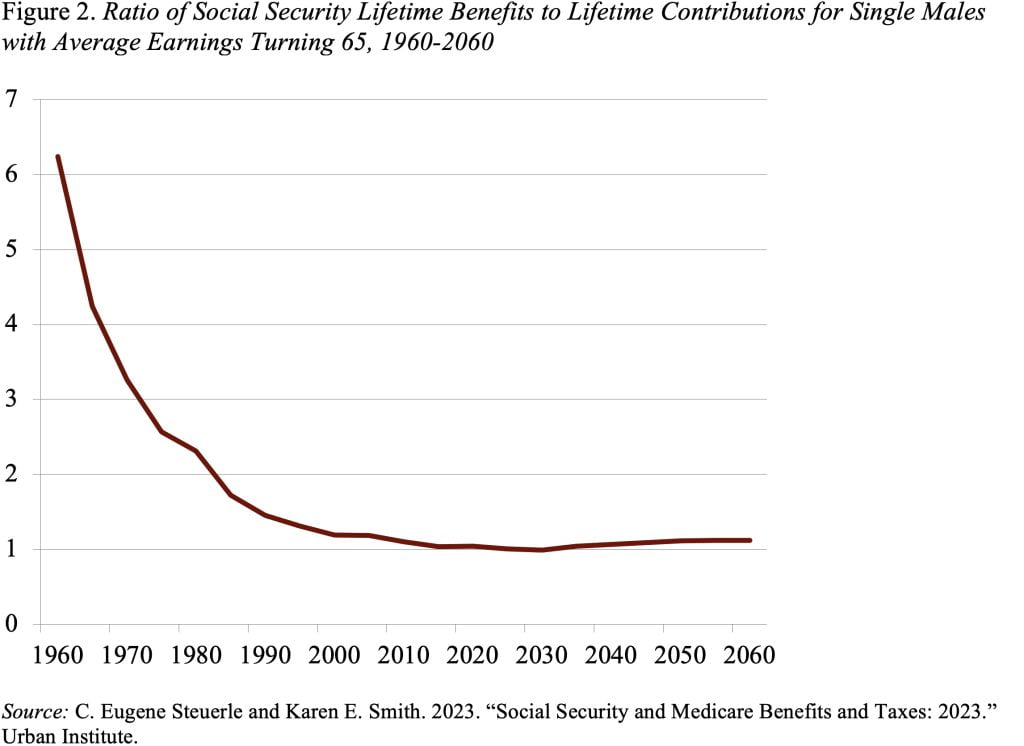

Third, the average male worker did receive benefits in excess of contributions for decades. But, the situation has improved dramatically (see Figure 2).

The bigger question is why the benefit/contribution ratio was so high historically and what that implies about Social Security’s finances going forward. With the exception of the buildup of reserves in the wake of the 1983 amendments and the imminent depletion of these reserves, Social Security has generally been financed on a pay-as-you-go basis. This funding method differs sharply from the original 1935 legislation, which envisioned the accumulation of trust fund assets like private insurance. The 1939 amendments, however, fundamentally changed the nature of the program and resulted in payroll tax receipts being used to pay benefits to retirees far in excess of their contributions. In essence, we gave away the trust fund.

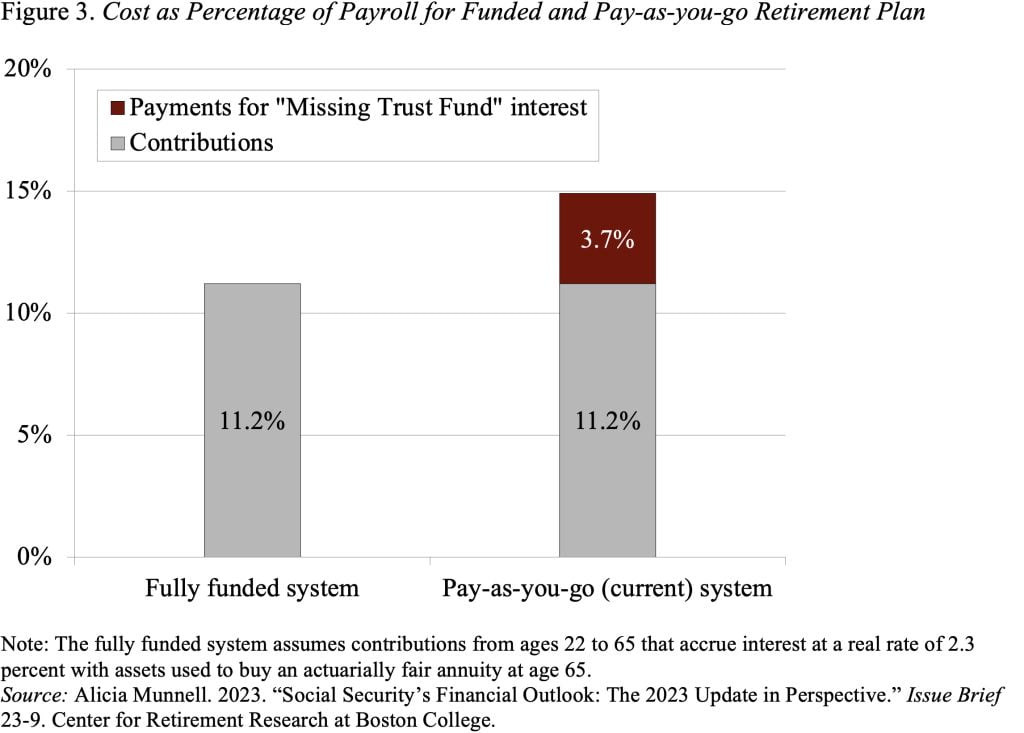

The cost to Social Security of giving away the trust fund is the difference in the required contribution rate to finance benefits under a funded retirement plan compared to a pay-as-you-go system. Under a funded system, the combined employer-employee contribution rate for a typical worker would be 11.2 percent of earnings to achieve a current-law scheduled benefit equal to 36 percent of average indexed earnings. Under our pay-as-you-go system, the total cost is 14.9 percent. The resulting difference – 3.7 percent of payroll – is due to the presence of a trust fund that can pay interest in a funded system but is missing in the pay-as-you-go system (see Figure 3).

How this additional cost associated with the missing trust fund should be financed is a real issue. Should workers be asked to pay more than the “normal cost” associated with a funded plan or should some of the financing come from general revenues? In no case, however, do disparities between lifetime contributions and lifetime benefits provide any guidance on how the shortfall in Social Security’s 75-year financing should be resolved.