Social Security in the Cross Hairs: Replacement Rates Still

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

SSA study shows that CBO numbers cannot be right.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has become a major player in the effort to show that Social Security is very expensive – huge 75-year deficit – and very generous – extraordinarily high benefits relative to pre-retirement earnings (replacement rates). These two developments together set the stage for cutting back on Social Security – something this country can ill afford given that the typical household approaching retirement has only $111,000 combined in 401(k) and IRA accounts. And those with 401(k)s are the lucky ones, one third of households will be forced to rely on Social Security alone.

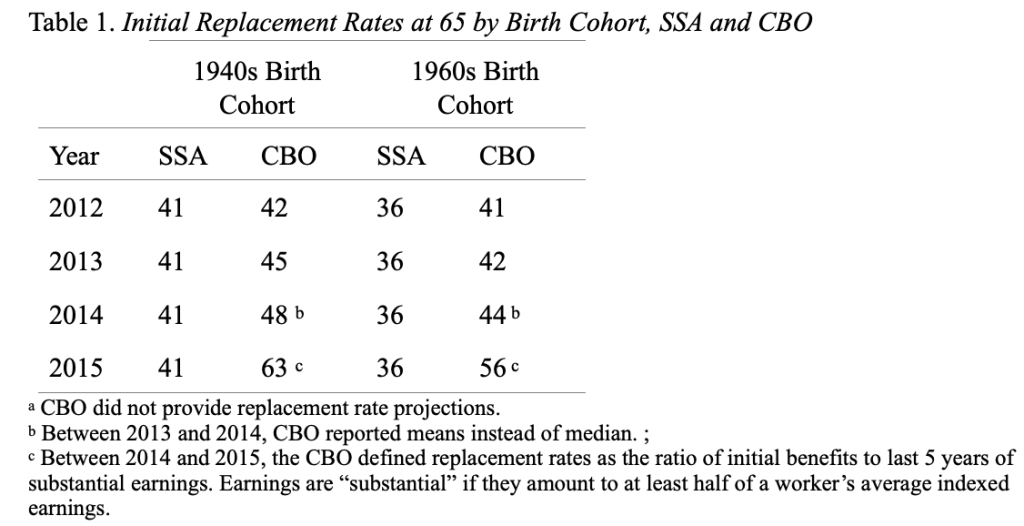

CBO’s measure of generosity is the most problematic. In 2015, the replacement rates jumped dramatically to extraordinary levels, suggesting the average worker receives benefits equal to about 60 percent of pre-retirement rather than 40 percent as reported for more than a decade by CBO.

In any event, the men/median issue is small potatoes compared to the change made between 2014 and 2015. Instead of computing replacement rates as the ratio of initial benefits to lifetime earnings adjusted for wage growth, the CBO related initial benefits to the average of the last five years of substantial earnings before age 62. And as you can see in Table 1, the CBO replacement rates jump to 63 percent for the 1940s cohort and to 56 percent for the 1960s cohort.

Suddenly, the CBO is telling a very different story than SSA and a very different story than its own numbers in the past. The change in the metric would not be expected to provide such a different answer, as work by the Social Security actuaries has shown. Putting out such a high number without any effort to reconcile it with the historical data is irresponsible. And those waiting for an opportunity to show that Social Security is excessively generous have pounced on the new CBO replacement rate number and publicized it in op-eds coast-to-coast.

Each year the Social Security actuaries project the system’s financial outlook over the next 75 years. This report usually comes out in April but this year was delayed to the end of July. This delay raised the question whether the delay was driven by controversy and intrigue or by the inability to get six people (the Social Security Commissioner, the Secretaries of Treasury, of Health and Human Services, and of Labor, and two public trustees) in a room to sign the document. At first, I thought the delay was more administrative than substantive, given that this year’s report looks very much like last year’s. But upon reflection, I think that the push to delete replacement rate data from Table V.C7 may have held up the release.

So, what is Table V.C7 and why is the deletion a big deal? The table shows for workers at different places in the income scale (very low, low, medium, high, and maximum) future benefits adjusted for inflation and benefits as a percent of pre-retirement earnings – commonly referred to as replacement rates. The trustees have deleted any measure of replacement rates from the report.

The deletion is the culmination of a concerted effort by a band of critics who argue that all is right in the world: people will have plenty of money in retirement. With respect to Social Security, these critics contend that the reported replacement rates grossly understate Social Security’s contribution to retirement income. In 2013 testimony before the House Ways and Means Committee, one critic reported that according to his calculations Social Security replaced 69 percent of pre-retirement earnings rather than the 40 percent reported in the tables (Biggs 2013).

So what’s going on here? Replacement rates arise in two contexts. The first pertains to financial planners’ advice to clients. The second is in the context of national pension plans, where replacement rates are an important guide to public policy. In the individual context, financial planners, who are usually dealing with people who have consistent earnings and above average income, often suggest that people need about 70 percent to 75 percent of their pre-retirement earnings to maintain their standard of living. In the national context, where the pattern of earnings varies widely and where many workers have zero earnings in the years just before retirement, a different metric is required. The United States follows the definition recommended by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) of calculating replacement rates as a percent of lifetime earnings revalued in line with economy-wide wage growth.

Truth be told, it would be best if the 70-75 percent “target” recommended by financial planners and the quoted replacement rates from Social Security were based on the same definition when gauging the contribution of Social Security to meeting retirement income goals. But given that the two numbers are calculated using different measures of preretirement income, the question is an empirical one. How different would Social Security replacement rates look if they were calculated on the basis of, say, the last five years of earnings.

A recent analysis by the Social Security actuaries of a random sample of 200,000 workers claiming benefits in 2011 provides an answer. The average retirement age for this group was 63.75. At the mean, the replacement rate for this group was 38.8 percent using the lifetime earnings indexed for wage growth and 39.2 percent using the last five years of significant earnings. Thus, empirically the two approaches provide the same picture.

How do critics get such high replacement rates? They use earnings in the last five years including years of zero earnings. In 2011, 15 percent of people claiming benefits had no earnings in the 5 years immediately prior to claiming. For these workers, the replacement rate would be infinite!! It makes no sense to include zero years in the denominator of the replacement rate calculation.

In short, no rational case can be made for deleting replacement rate numbers from the Trustees Report. And doing so has serious policy implications. If the only numbers provided to policymakers are dollar amounts rising over time – without any reference to the earnings these benefits are replacing – they will think that slowing the rate of increase would do little harm. But slowing the growth in inflation-adjusted benefits reduces the percent of earnings replaced. If Social Security replaces less, then future workers must depend on what is now a fairly wobbly 401(k) system for more. Without replacement rate numbers, policymakers will have no idea what they are doing to the retirement security of future workers as they consider alternative Social Security provisions.

This is not inside baseball. This is important.