Social Security Is Loved by People Across the Political Spectrum

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

But they want only high earners to pay for the fix.

With all the DOGE-driven turbulence at the Social Security Administration, it may have gotten lost that 2025 is the 90th anniversary of the program. In celebration, a number of organizations have put out reports that assess the current status of the program and suggestions for reform. In an effort to catch up on my reading, I just finished “Social Security at 90,” which was released in January by the National Academy of Social Insurance (NASI).

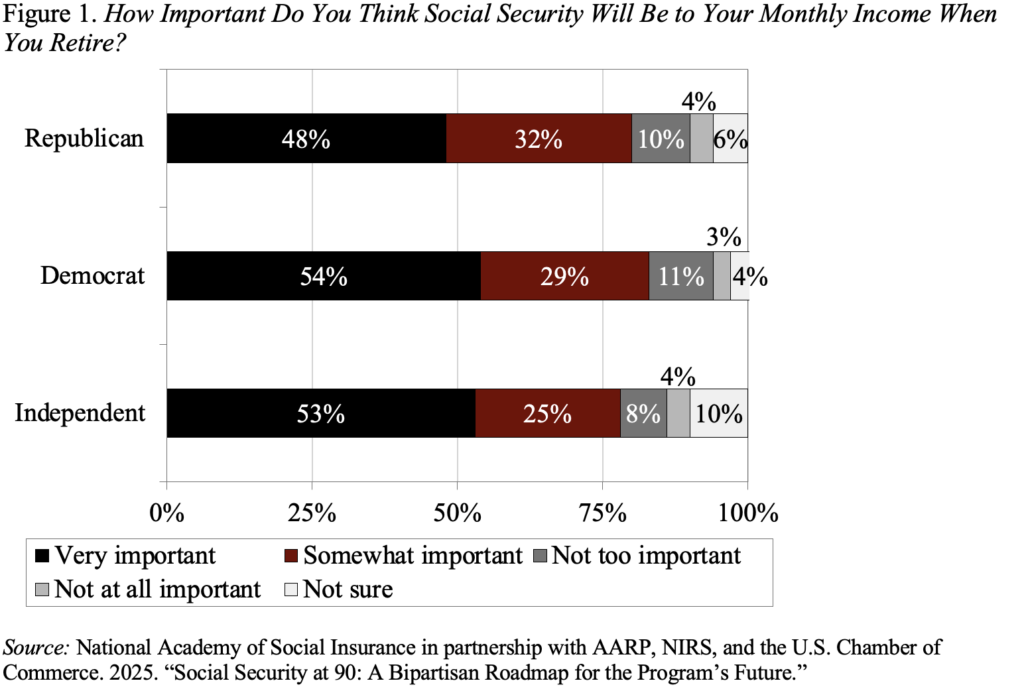

This report highlighted the results of a survey of about 2,000 respondents on their views of Social Security and possible ways to eliminate the program’s 75-year deficit. When respondents were asked how important they thought Social Security benefits would be to their monthly income once they retired, between 65 and 90 percent replied “very important” or “somewhat important.” This pattern held across political affiliation (see Figure 1), age group, educational attainment, and income level.

This broad-based support of the program was encouraging in a period when the press reports that the program will go bankrupt in the early 2030s and many young people think they may never get any Social Security benefits. Neither claim is true. Social Security is not going bankrupt in the early 2030s. Rather, the trust fund reserves that bridge the gap between the program’s revenues and outlays will be depleted in the 2030s. However, the payroll taxes that continue to roll in can cover about 80 percent of promised benefits. Hence, even if nothing is done, people will continue to receive the bulk of their benefits.

No one, however, wants to see an immediate 20-percent across-the-board benefit cut in Social Security retirement benefits. So, much of the NASI report focuses on how the respondents would fix the problem. Here the findings are less satisfying. The respondents would essentially raise more money by taking the cap off the maximum taxable earnings – subjecting everybody’s full earnings to the payroll tax – and raising the payroll tax rate from 6.2 percent to 7.2 percent for both employees and employers.

While I think that a modest increase in the payroll tax rate should be part of any package to close Social Security’s 75-year shortfall, I really do not like the notion of taking the cap off maximum taxable earnings. My first concern is that it dissolves any link between payroll tax contributions and benefits, which in the long run could well undermine support for the program.

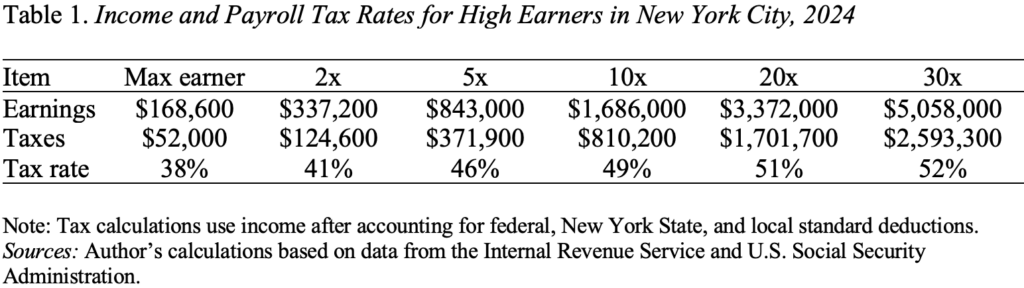

More broadly, I am concerned about raising taxes further on people who get all their income in the form of wages and salaries. Indeed, a quick calculation for those living in New York City suggests that really high earners pay more than half their compensation in income (federal, state, and city) and payroll taxes (no taxable maximum on the Medicare tax plus a 0.9-percent tax on earnings above $200,000 for singles and $250,000 for married couples) (see Table 1). Efforts to increase tax revenues should aim at investors who put penny stocks in Roth IRAs, people who enjoy the step-up in basis on their assets at death, and the private equity guys who enjoy capital gains rates on carried interest.

In short, surveys may be helpful for gauging the public’s views about the value of a major program like Social Security, but I don’t think they’re particularly useful in designing reform proposals. For my part, I’m sticking with Wendell Primus’s package of benefit cuts and tax increases.