Social Security Really Helps Low Earners – Even Though They Might Not Live as Long

Alicia H. Munnell is a columnist for MarketWatch and senior advisor of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Including disability benefits provides a more complete picture.

The Social Security actuaries just released a study that takes a new look at the progressivity of the Social Security program – that is, the extent to which it pays relatively more generous benefits to low earners than to high earners. The usual story focuses on “money’s worth” of retirement benefits, highlighting the offsetting effects of two factors. On the one hand, Social Security helps those Black workers and others with low education – and therefore low earnings – through the progressive benefit structure. On the other hand, the value of lifetime benefits inherently increases for individuals who tend to live longer, who are generally more-educated, White workers with higher earnings.

The new study directly addresses this issue – progressive benefit formula vs. longer life expectancy – by using different life expectancies for low and high earners. It goes a step further, however, by including Social Security’s disability insurance in the analysis. While low earners have shorter life expectancies, they are more likely to qualify for disability insurance. The major finding is the difference in life expectancy by earnings is roughly offset by the difference in disability by earnings levels.

Before looking at the results, the authors of the new study acknowledge that their “money’s worth” approach does not reflect the additional value that Social Security benefits offer in terms of “peace of mind.” This insurance reduces the financial risks associated with extreme outcomes such as death or disability at a young age or survival to very old ages. As noted in an earlier blog, my colleagues examined the distributional aspects of one “peace-of-mind” component – namely, the longevity insurance associated with retirement benefits. Because Social Security provides a life annuity, it offers households protection against outliving their resources. The value of this protection increases with the unpredictability of their lifespan. It turns out while low earners have lower average lifespans than others, they face greater uncertainty around these averages.

Turning back to Social Security’s new money worth’s analysis, the main exercise involves calculating the internal rate of return for 4 types of hypothetical workers, born in 11 different years, at 5 points in the earnings distribution. Moreover, because the Social Security program’s projected income will not cover scheduled benefits after 2034, the results are shown under 3 financing scenarios – current law, increased payroll tax, and reduced benefits. Finally, the results involve 2 versions of each table – one without any adjustment for the varying life expectancy and differences in disability incidence and one without. In all, the total is 6 tables, each containing 220 internal rates of return.

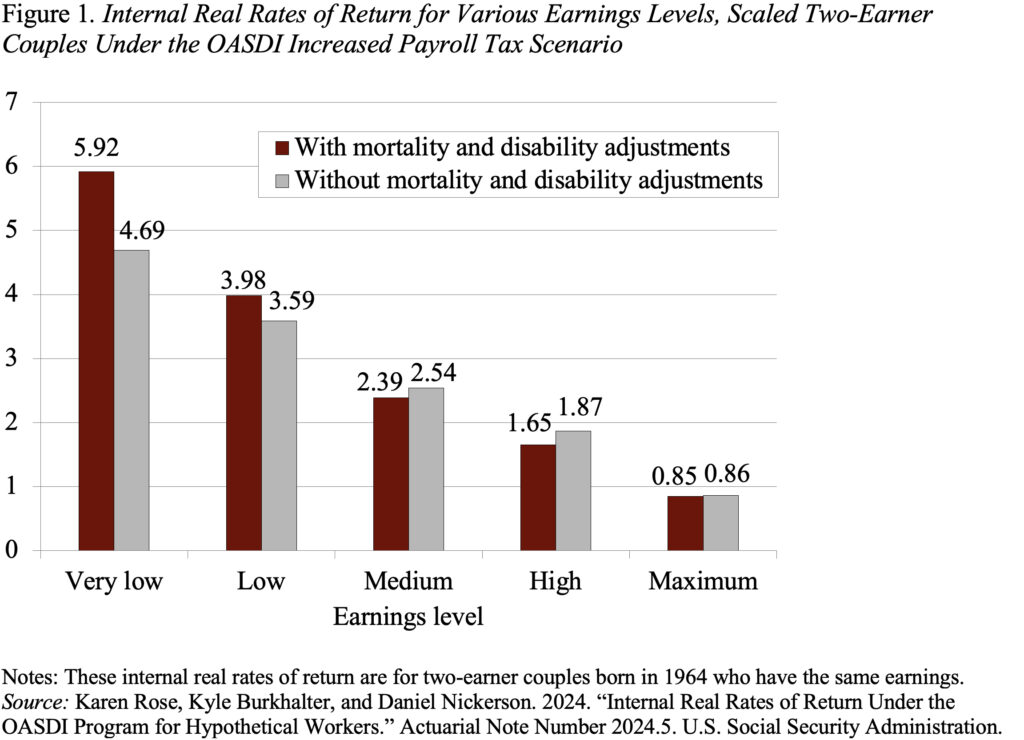

Because the story is consistent across scenarios, the basic finding can be summarized by looking at one group of earners – two-earner couples – born in 1964 under the scenario that assumes that the payroll tax is increased to cover promised benefits. The results show that the program is progressive – rates of return decline as earnings increase – and that the pattern is very similar with and without accounting for differences in life expectancy and the incidence of disability (see Figure 1). That is, as noted at the beginning, the difference in life expectancy by earnings is roughly offset by the difference in disability by earnings.

The only consideration to add back is the recent evidence about the “peace-of-mind” that Social Security offers by reducing the risk associated with extreme events. At least on the retirement side, the benefits of longevity insurance are also progressive because the value of this insurance increases with the unpredictability of lifespans, and low earners face greater unpredictability. Thus, Social Security benefits are even more progressive than the Social Security actuaries’ new study would suggest.